Virtual Town Meeting Dissertation

Overview: Virtual Town Meeting

Dr. Peter Frederick Sielman

Dr. Peter Frederick Sielman is credited as the brainchild behind the [Salem, Connecticut] Virtual Town Meeting and is the author of the following text and supplemental media. The following is a draft of Dr. Sielman’s thesis for his Doctoral degree in Political Science at the University of Connecticut, and the final copy of his dissertation can be viewed and purchased from the University of Connecticut virtual library here.

Abstract

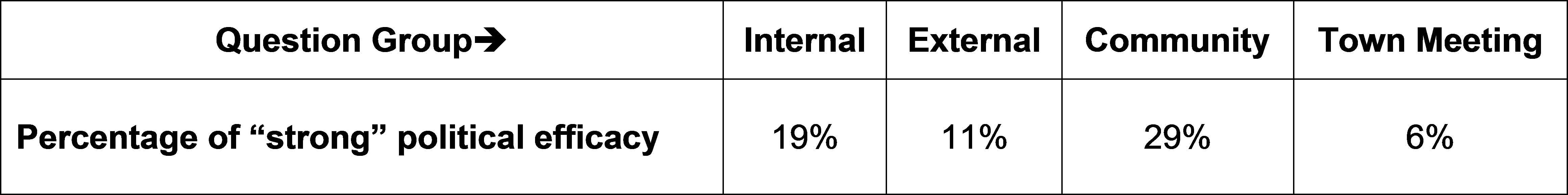

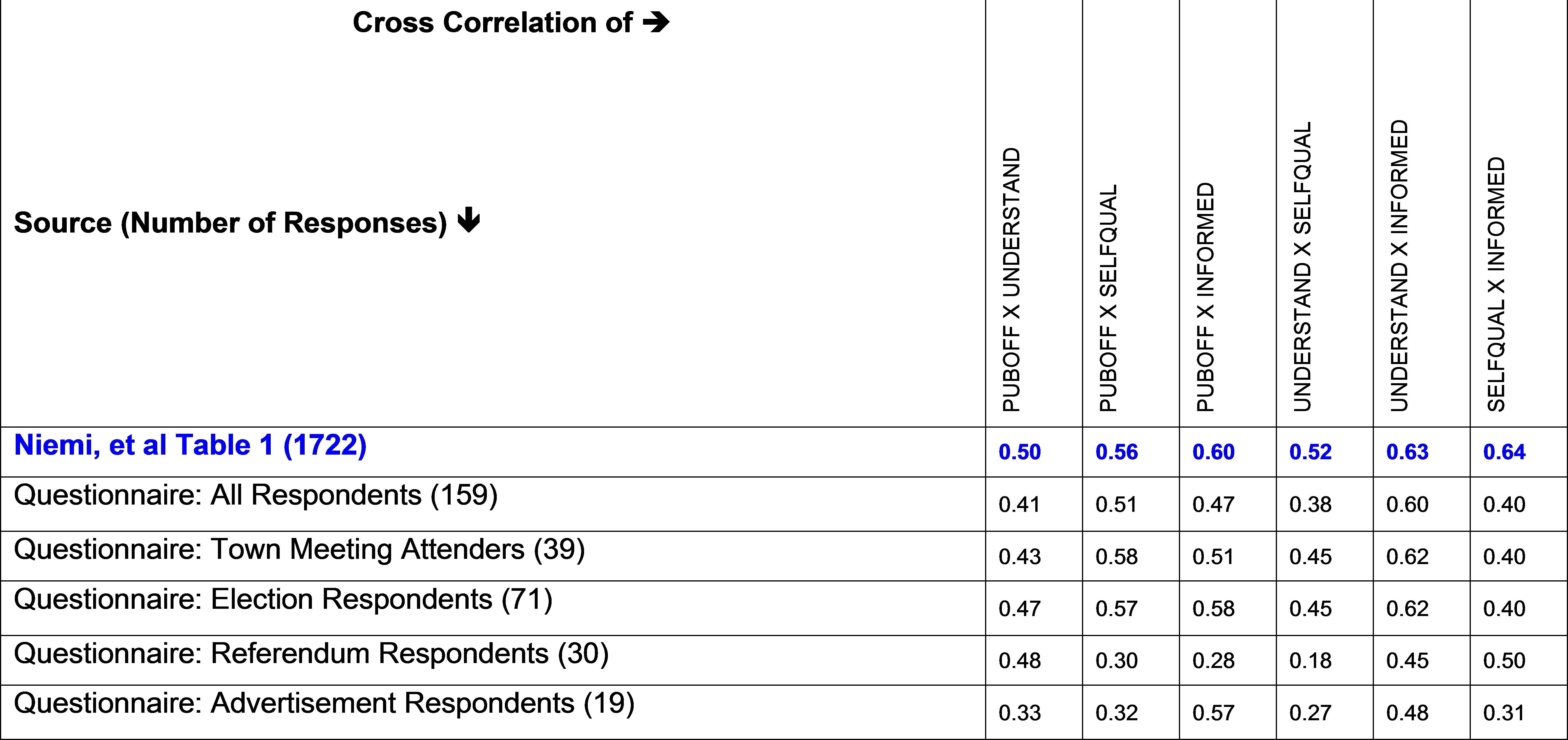

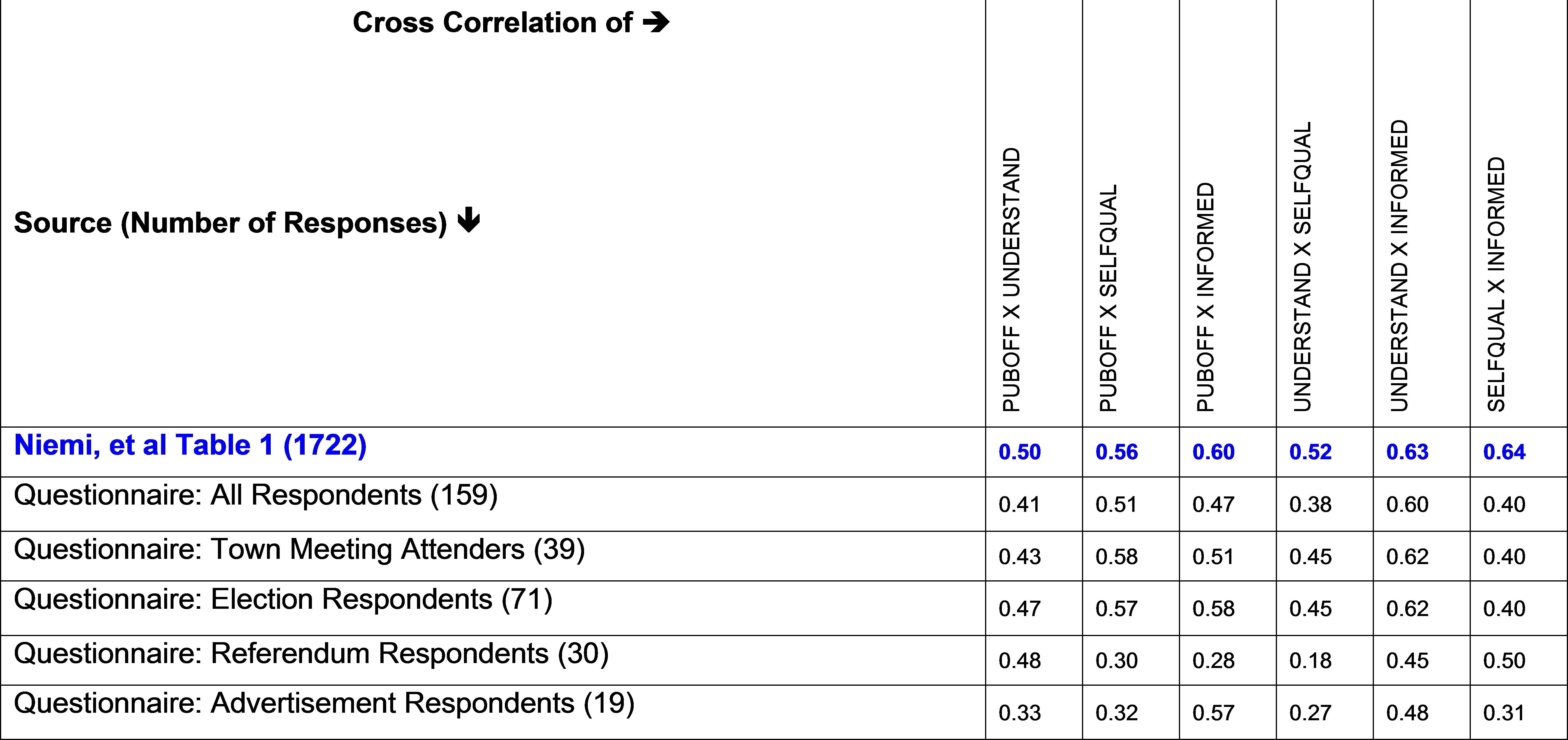

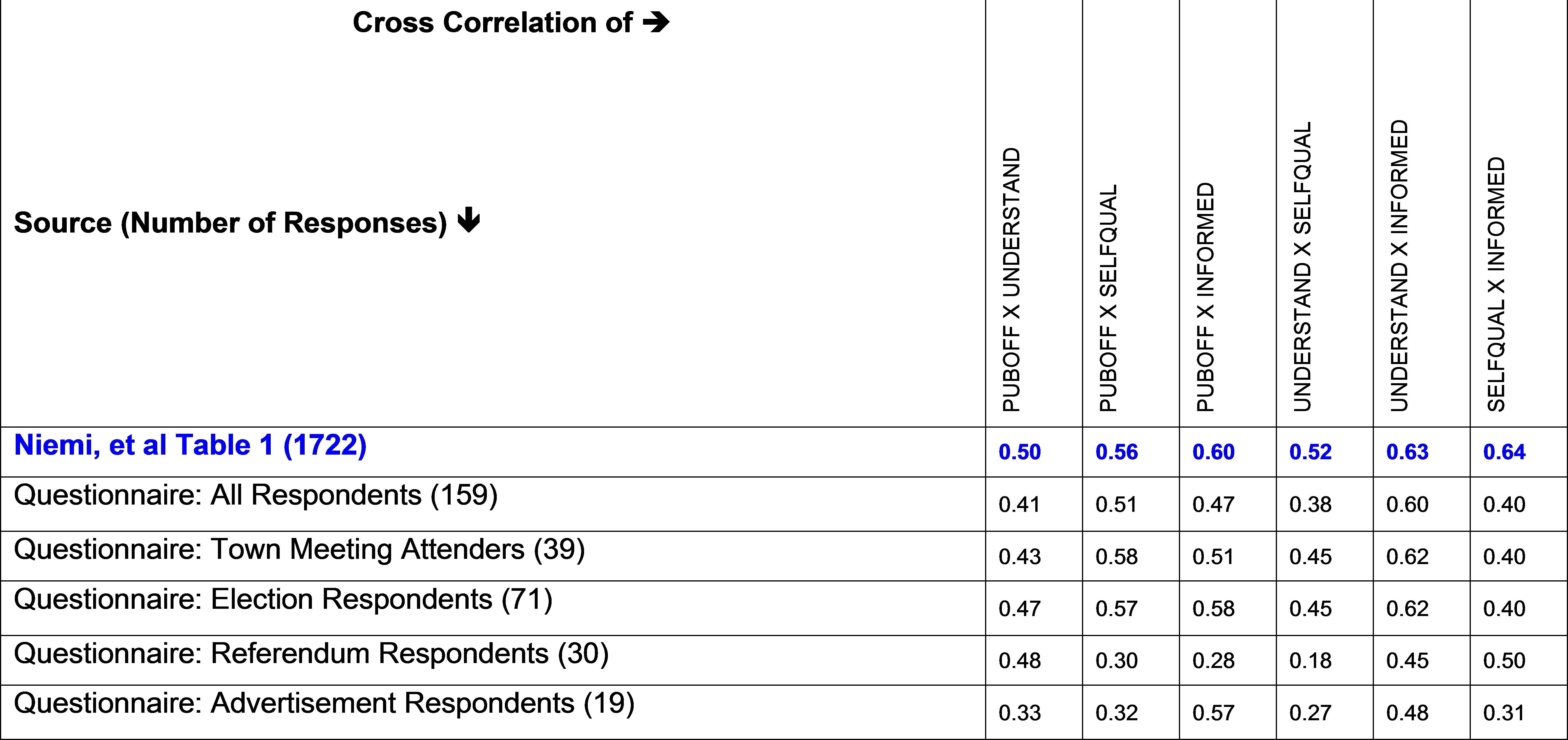

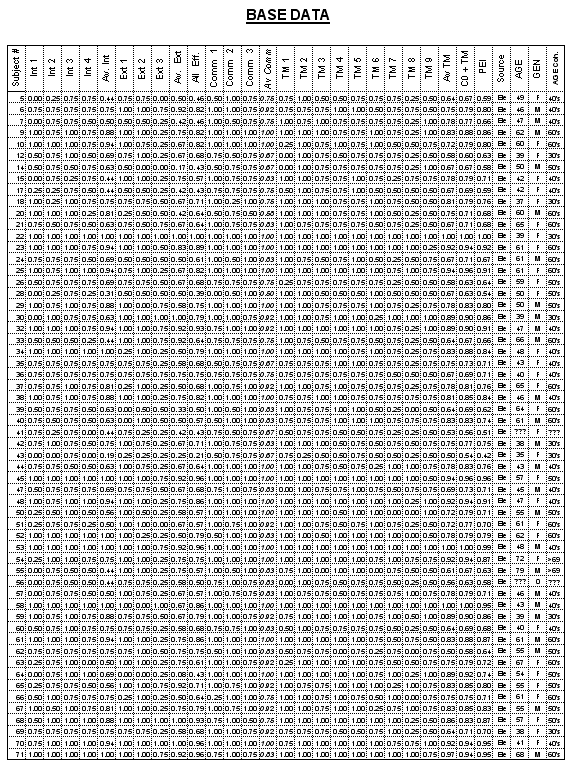

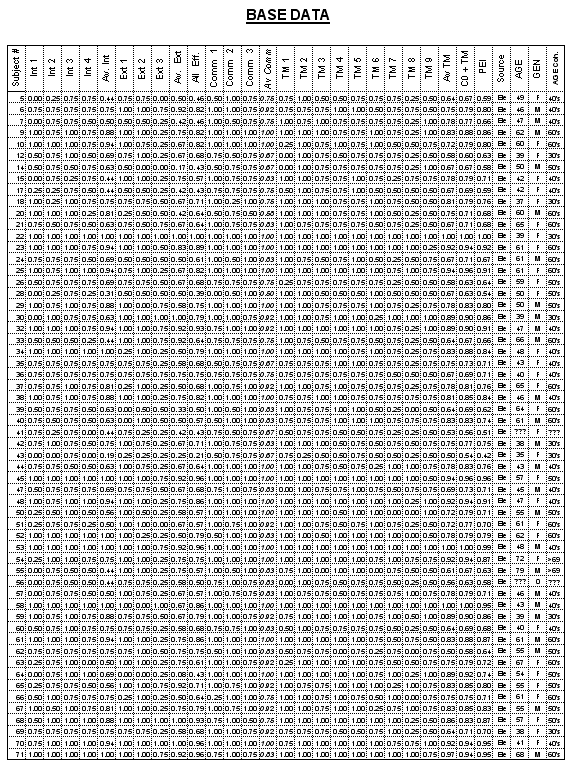

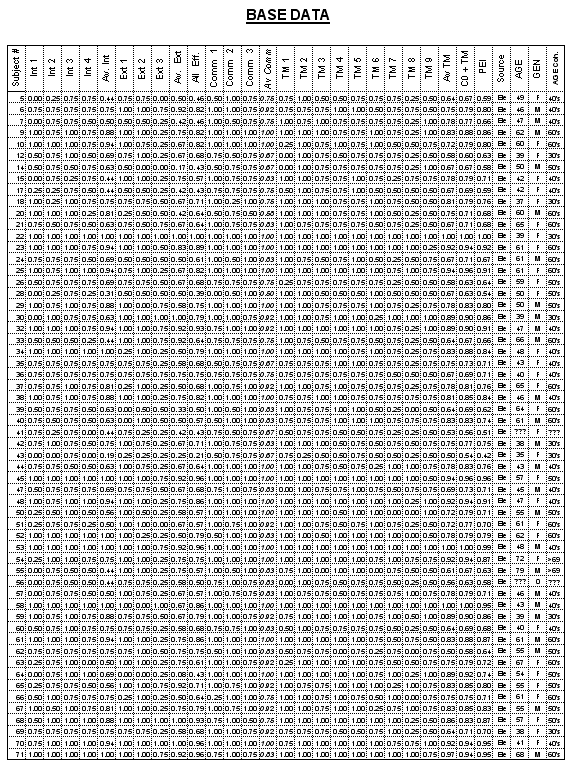

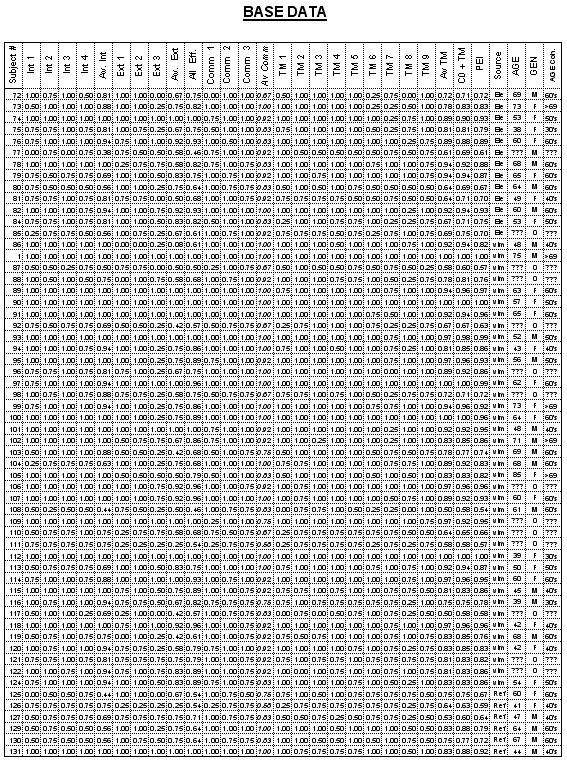

The concept of virtual town meeting permits eligible voters to participate in the legislative function of town meetings without the necessity of being physically present. Remote participation is via electronic means, using live cablecasting and webcasting of the physical town meeting and live emailing to permit remote participants to be part of the deliberations and to vote on motions. ^ This dissertation reports on tests of the virtual town meeting concept carried out in Salem, Connecticut in the period 2008–2010. It describes the electronic implementation hardware and software employed in the tests and the processes used to assure the smooth and secure functioning of the virtual town meetings. ^ This dissertation also reports on a case study survey of eligible town meeting participants to ascertain the distribution of feelings of political efficacy amongst various groups, age cohorts and genders. The results of the survey are compared to NES data cited by Niemi, Craig and Mattei. Conclusions are drawn with regard to how to measure and index political efficacy data, the correlation between the availability of remote town meeting participation and feelings of political efficacy and the potential role of virtual town meetings in future evaluations of participatory and deliberative democracy.

Citation

Sielman, Peter Frederick, “Virtual town meeting” (2010). Doctoral Dissertations. AAI3420185.

https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/AAI3420185

Chapter 1: Introduction

This is a study of the relationship between participatory and deliberative democracy and political efficacy as applied to the town meeting form of government. It is unique because it documents and examines the first example of a “virtual” town meeting in which citizens can participate remotely in a legally binding municipal town meeting. Given this uniqueness, I review the relevant literature in the context of the tests and associated case study that I have conducted that were focused on two groups of participants. The two groups are defined by the nature of their participation. One group attends town meeting in person; the other group is able to participate remotely in the same town meeting via electronic means. Both groups can listen to and see the deliberation. Under the control of the moderator, both groups can participate in the deliberation and propose motions consonant with the call of the meeting. Both groups can vote on motions raised at the town meeting. This form of town meeting is called a virtual town meeting and is legal within the statutes of the State of Connecticut (Sielman 2006).

Virtual town meeting provides remote participation through the application of simple, standard, widely used electronics. The meeting is viewable in real time[1] and, with the utilization of 2 cameras, the remote participant may actually have a better view of attending speakers than the remainder of the attendees. Remote participants contribute to the deliberations and vote on motions through the use of email. The moderator controls who “speaks” (both in person and remotely) by having a laptop computer that displays the incoming email traffic.

The primary objective of the virtual town meeting tests was to determine whether or not providing the possibility of remote participation would increase the number of people who do participate. Virtual town meeting is not aimed at getting all eligible voters to participate in the town meeting’s legislative function, but rather its aim is to eliminate some of the perceived barriers to participation. The tests were aimed at verifying the results of a previous survey (Sielman, 2006) that predicted that 5 % of the eligible voters who had not participated in town meetings might do so if it could be done remotely. For security purposes, the virtual town meeting process requires potential remote participants to register their unique email address. Of those who have signed up at this writing, 12% participated in the last virtual town meeting.

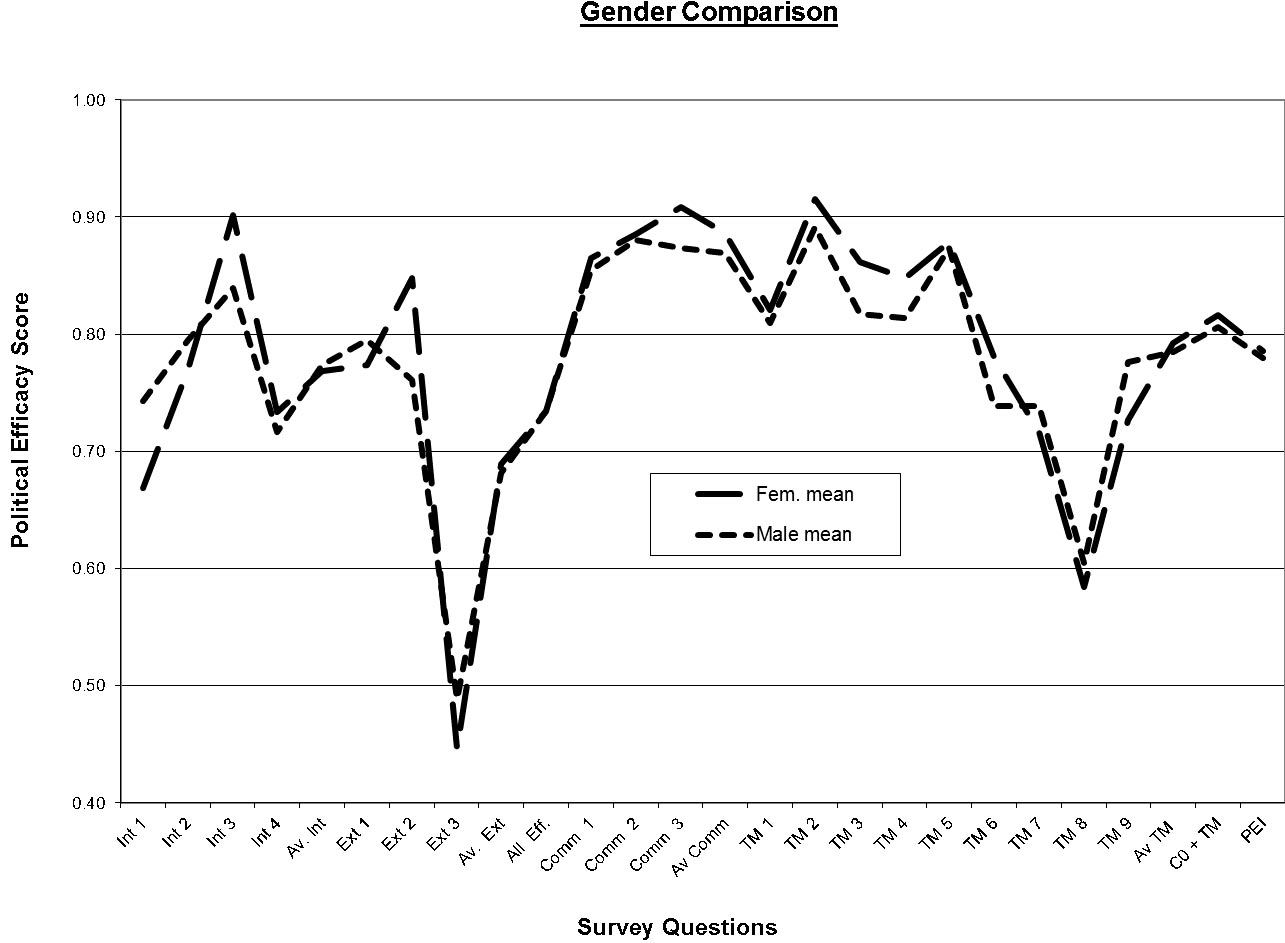

A secondary objective of the virtual town meeting tests was to measure the political efficacy feelings of participants, both town meeting attendees and remote participants. The measurement mechanism was a 19-question survey modeled after the NES political efficacy surveys. Analysis of the survey data compared respondents on the basis of their age, gender and the circumstances under which they signed up for potential virtual participation. Those who remotely participated in the last virtual town meeting and had filled out earlier survey questionnaires were asked to do so again after their remote participation to enable a PrePost test comparison of whether or not their remote participation altered their feelings of political efficacy.

The details of the tests, a description of the different hardware implementations and the processes used to conduct virtual town meetings are presented in chapter 3. This chapter also provides the numerical participation numbers achieved in the tests that have been run to date. Chapter 4 presents and analyzes the survey structure, compares the responses to those measured by Niemi, Craig and Mattei (1991) and plots the variations of responses with age, gender and survey venue. This chapter also presents and analyses the PrePost test data and draws conclusions about the relationship between participation and feelings of political efficacy.

Chapters 3 and 4 represent the meat of the study. They are preceded in Chapter 2 by a review of the scholarly literature germane to participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, the town meeting form of government, political efficacy and the application of technology to these fields. In Chapter 5, I summarize the conclusions that I believe can be fairly drawn from the test and survey, and their relationship to the literary background. Virtual town meeting is in its infancy. In the context of the ever increasing use of the Internet, it is my conviction that this concept will evolve, not only in its application to towns that have the town meeting form of government, but that we will also probably see its application to other implementations of participatory and deliberative democracy.

Chapter 2: Background

Town meeting is a form of deliberative and participatory democracy. There has been a large outpouring of scholarly literature on deliberative democracy and participatory democracy in the past three decades. Scholars disagree on both the merits of deliberative democracy and participatory democracy and the potential tensions associated with them, as well as about the methods that are most suitable for scholarly research in these fields. The aim, here, is to identify and evaluate the portions of this corpus that are relevant to a virtual town meeting and to concentrate on those sections of the literature that address political efficacy effects on the participants.

The premier authors who have studied and reported on the town meeting form of government[2] are Mansbridge (1980), Zimmerman (1999 & 2002) and Bryan (2003). Mansbridge reported in detail on the annual town meeting of a Vermont town with a population of 350, emphasizing the correlations between attendance and speaking at town meeting with measurable characteristics such as age, gender, length of residence in town and socioeconomic status. Her correlations were based on interviews/questionnaires with 69 residents (1980, 99). Mansbridge selected a Vermont town rather than a Massachusetts or Connecticut town for her study because the latter: “…were run by an obvious professional and business elite” (1980, viii). By contrast, this study is based on the Town of Salem, Connecticut with a population of approximately 4,000. After more than 20 years of attendance at Salem town meetings (of which there are several every year) it is not clear to me that the town meetings are run by “an obvious professional and business elite.”

Zimmerman (2002) concentrates on the current (and growing) problems associated with reduced participation in town meetings and offers up several strategies that have been used to increase participation in order to enhance democratic legitimacy. These strategies include child and elder care provision, transportation assistance, mailing meeting warrants to all households, using a consent calendar to speed up meetings, seeking citizen input in warrant generation, dividing a single meeting into two or more meetings and allowing proxy votes (1999, 175-179). While Zimmerman examined many strategies, he did not include remote participation via electronic means, the approach used in a virtual town meeting.

Bryan, who claims the inspiration for his work came from a meeting with Mansbridge (2003, ix), reported on data collected by his students at town meetings all over Vermont for over 30 years covering more than 1435 separate sessions of town meetings. Bryan, who is very enthusiastic about the institution of town meetings as the purest form of ”real democracy,” attempts to correlate attendance at Vermont’s annual town meetings with town population, affluence, growth rates, relationship to school districts and contention level of the items on the meeting call. He concludes that no single variable is a sure surrogate for attendance although town size affects overall attendance numbers but not percentage of eligible participant attendance. However, he states that: “beyond town size, issues are the single most important variable that draws citizens to town meeting” (2003, 233).[3]

While these three authors have done the most sustained research on town meeting, there are many others whose work is relevant to this study. For my purposes, the four most important areas of research examine: participatory and deliberative democracy, implementation schemes for increasing opportunities for participation and deliberation, the impact of modern communications technology,[4] and political efficacy. I address the literature associated with participatory democracy combined with the literature associated with deliberative democracy because town meetings represent a combined form of participatory and deliberative democracy. While one can have participation without deliberation—for example many of the traditional measures of political participation such as voting, fund-raising, contacting a representative, and campaign activity do not necessarily incorporate deliberation—the obverse is not generally true. Some of the literature addresses only participation and some addresses both participation and deliberation, but I extract from both the issues relevant to my research.

Participatory and Deliberative Democracy

Although some authors deal separately with deliberation and participation, in the context of a virtual town meeting, participation and deliberation are inextricably intertwined. To the extent possible, in reviewing the germane literature, I have organized the material to sequentially address:

-

- The perceived advantages and disadvantages of participatory and deliberative democracy [Values].

- Evaluation of practices that enhance participatory and deliberative democracy [Practices].

- Proposals for effective political science studies of participatory and deliberative democracy [Studies].

- Schemes that have been proposed to widen the use of participatory and deliberative democracy [Dissemination].

I am fortunate that two distinguished scholars, Diana Mutz and Dennis Thompson, have recently published broadly applicable survey articles on participatory and deliberative democracy (Mutz 2008; Thompson 2008). Each of these articles addresses the other and provides references to most of the relevant scholarship. Both of these articles reference the review of the relevant literature produced by Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs (2004), which covers “Public Deliberation, Discursive Participation and Citizen Engagement.” With these major guides to the corpus, I am able to extract the theoretical and empirical highlights of deliberation and participation that are germane in the context of a virtual town meeting.

Values

Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs (2004) organize their review of deliberative and participatory democracy by defining public deliberation, listing the assumptions that underlie its purported benefits, and listing what we know and don’t know about the impact of public deliberation on civic engagement (divided into: political talk, social psychology, case studies and survey-based research, experimental research on public deliberation and the potential role of online deliberation). They accept Chambers’ definition of deliberation:

[D]eliberation is debate and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opinions in which participants are willing to revise preferences in light of discussion, new information, and claims made by fellow participants…an overarching interest in the legitimacy of outcomes (understood as justification to all affected) ideally characterizes deliberation (2003, 316).

Unfortunately, they do not reference current town meetings and refer to the concept only at the beginning of the paper as “town hall meetings of colonial New England” as if they had died out with powdered wigs (2004, 315-316). This position is unpersuasive because virtual town meeting clearly fits within the confines of Chambers’ definition. The virtual town meeting is the legislative body of the town that discharges legislative business after engaging in debate and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opinions. The legitimacy portion of the definition is especially cogent, since virtual town meeting also aims at arriving at justified decisions.

Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs go on to list five necessary characteristics of effective discursive participation (2004, 318):

-

- Discourse with other citizens.

- Discourse as a form of participation’

- Related to formal institutions of civic and political life.

- Can occur through a variety of media.

- Focused on issues (local, national or international) of public concern.

Virtual town meeting meets all of these criteria. Citizens participate by engaging in discourse within a formal political institution, and in the unique case of the virtual town meeting, they do so through a variety of media. In the virtual town meeting characteristic (5) generally focuses on local concerns, but citizens occasionally pass “sense of the meeting” resolutions on topics of wider concern.

Beyond these definitional issues, Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs, referencing many other authors, summarize the benefits of public participation in deliberation. They argue that public participation can lead to empathy, to an expanded sense of interest in community benefits, and to exposure to “reasoned argumentation” (2004, 320). They also point out that participants learn deliberation skills, are more likely to become engaged in politics, and will likely have greater faith in democracy and the legitimacy of their form of government. Quoting Chambers (2003, 318) on whether or not deliberation changes minds, they conclude that under the right conditions it does and that it has the side benefit of promoting tolerance and encouraging a public-spirited attitude (2004, 320). Berry, Portney and Thomson have an even broader view than most authors of the benefits of participatory democracy. Their view is particularly applicable in community settings:

In a participatory democracy, individual action in the affairs of the community is a critical part of the way people mature… participation is a key to transforming individuals so that they develop bonds with their neighbors, come to understand shared values and take on new identities… Competence in political participation is something people learn through practice and experience (1993, 258).

The tests conducted as part of this study specifically examine whether the act of participating in virtual town meeting enhances the participants’ sense of political efficacy.

Surowiecki addresses decision-making by expanded groups by pointing out that whatever new members do know is not totally redundant with what everyone else knows and hence the diversity improves the decision making (2004, 31). Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs echo Surowiecki’s claim about collective decisions being superior because more information can be brought to bear (2004,327-8). They further claim that when people feel greater accountability for their decisions, they are more likely to be objective and unbiased. In virtual town meeting, because the participants are acting in an important official capacity that can have direct and significant effects upon their lives, they feel the accountability to which Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs refer. Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs also report on some research that aims to test the hypothesis that collective political decisions are superior to individual ones. The artificial tests provided groups of respondents with information about, and then asked them to discuss, three fictitious candidates before choosing for whom to vote. Their results were that information was not aggregated (2004, 332). The reality and the absence of artificiality inherent in virtual town meeting makes it a much better testing ground for the value of collective political decisions.

Virtual town meeting builds on the theories of authors like Barabas who claim that deliberation increases knowledge and alters opinions if participants hear diverse messages and are willing to keep an open mind (2004, 687). Cohen echoes and amplifies this when he says that: “We have a strong case for political legitimacy when the exercise of political power has sufficient justification” (1998, 222). Beyond increases in knowledge, Morrell addresses the attitudes that may result from deliberation:

Establishing processes that encourage all citizens to empathize with one another will result in deliberations characterized more by mutual respect, civic magnanimity, reciprocity and a commitment to continued deliberation. (2008)

Gambetta extends this idea in a different direction when he points out that: “…deliberation… spurs the imagination indirectly if it reveals that, on all known options, no compromise is possible, for this provides an incentive to think of new ones” (1998, 22). [5]

Verba, Schlozman and Brady have a more nuanced perspective on the relationship between participation and a sense of the common good. They caution that even though they were surprised by the extent to which respondents believed their actions were motivated by common good:

[W]e would not presume to assess the extent to which the participatory system …achieves something that might be characterized as the common good. Even when the public good is conceived as something more than the summation of individual preferences, there are competing conceptions of the good of all… This does not mean that they do not also use their participation as a vehicle for furthering their own narrow interests or … that they do not sometimes construe what is good for themselves as being good for the country. (1995, 528-9)

Throughout his book, Bryan (2003) is very positive about the benefits of participation for the participants in town meetings. He includes civics education, tolerance, forbearance and acquaintance with the rules of group deliberation. Gargarella (paraphrasing Pateman) agrees with Bryan in the sense that deliberation may also be important in “educating” people to act impartially and help people live with others (1998, 261).

Not all authors subscribe to these benefits. Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs relate that many citizens do not wish for, and indeed might react negatively toward, efforts to engage them more directly in political decision making through deliberation. Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2003) are perhaps the most forceful detractors of the value of participation in decision-making, arguing that the paramount drive of most voters is conflict avoidance. They point to the conflicts that can evolve from face-to-face deliberation, selectively quoting Mansbridge (1983, 68, 69, 273, 276-7, 293 and 295) and arguing that some [emphasis added] voters prefer to place their governance in the hands of empathetic non-self-interested decision-makers (ENSIDs). They believe that some citizens take the view that “debate is not necessary or helpful” (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2003, 143). They express doubt about the notion that participation educates participants to practice greater tolerance[6]. Mutz agrees partially with Hibbing and Theiss-Morse when she writes:

My own observations generally concur with Hibbing and Theiss-Morse in some respects. …many people do not like conflict and prefer not to talk about politics with those who have conflicting views. But I diverge from their conclusion, which suggests that because people generally do not like it, we should not worry too much about whether it happens. (2006, 90)

Thompson is critical of some of the detractors of deliberative democracy on the basis of the methodology employed by them in reaching their conclusions. His point is that, based on isolated passages from various theoretical writings:

They …extract a simplified statement about one or more benefits of deliberative democracy, compress it into a testable hypothesis, find or (more often) artificially create a site in which people talk about politics, and conclude that deliberation does not produce the benefits the theory promised and may even be counterproductive. (2004, 498)

Although there is a dearth of proof for Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s opinions, the important fact for virtual town meeting is that it is aimed at increasing participation, not seeking universal participation[7]. As underlined above, the fact that some citizens, or even many citizens, do not wish to participate in town meetings does not preclude the fact that there are some citizens who can contribute to and benefit from participation in deliberation and legislative voting via the mechanism of virtual town meeting. As pointed out by Rogowski in his discussion of Pateman’s work: “Those who decline to participate, or who participate only under duress or only perfunctorily, have made no commitment” (1981, 301). Surowiecki is also skeptical of trying to interest everyone in participating in deliberative democracy:

The ideal for “deliberative democracy” makes an easy target for criticism. It seems to rest on an unrealistic conception of people’s civic-mindedness. It endows deliberation with almost magical powers. And it has a schoolmarmish, eat your spinach air about it…. [people don’t] want to be told to take a holiday because it’s time to talk politics. (2004, 261)[8]

Practices

Bohman, who also provides a survey article of the deliberative democracy literature, draws conclusions about topics requiring careful study:

[D]emonstrating its feasibility and clearly understanding its limitations ultimately makes deliberative democracy a more, rather than less, appealing basis for genuine reform and innovation (1998, 423).

In addressing the social psychology research applicable to participatory and deliberative democracy, Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs, citing Mendelberg (2002) and others, arrive at the following [paraphrased] conclusions:

-

- Face-to-face communications is the single greatest factor in increasing the likelihood of cooperation.

- Talking allows group members to demonstrate their genuine willingness to cooperate and to determine others’ willingness to do so.

- Deliberation helps them to see the connection between their individual interest and that of the group.

- The group consensus that emerges from talk appears to lead to actual cooperative behavior, with more talk leading to more cooperation.

- However, these studies cannot demonstrate that altruism (as opposed to self-interest) is the prime motivator for cooperative behavior (2004, 324).

The structure of virtual town meetings appears to be in line with that suggested by the social psychologists, particularly in that it makes decisions by majority rule rather than seeking unanimity.[9] Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs report on an artificial game theory experiment by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2002). They note that:

The Hibbing & Theiss-Morse experiments do not fully capture the action of public deliberation; for example, the interactions occurred only between subjects and decision makers rather than across subjects… Nonetheless these experiments add to the evidence that the positive impact of discursive participation is strongly context dependent and tied to both process and outcomes. (2004, 333)

Thompson lists standards of which we should be wary that sometimes are applied to participatory and deliberative democracy. These include consensus—which Mansbridge has pointed out is not necessary and may be counterproductive—and justice. As Thompson notes, “the empirical challenges of isolating the effects of the deliberation on justice … are formidable” (2008, 508). Barber goes further by arguing that: “where consensus stops… politics starts” (1984, 129).

One of the interesting points stressed by Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs is that the important way to improve deliberation is to make sure that the debate is complete and the public has an opportunity to be engaged. Increasing the level of participation through the mechanism of virtual town meeting fits Fishkin’s concept in the public engagement sense. It is the responsibility of the moderator to assure the completeness of debate. In referring to New England town meetings (putting Mansbridge’s 1983 work in context), Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs summarize Mansbridge’s distinction between unitary (consensus) and adversarial (majority rule) democracy. Mansbridge’s unitary democracy “is most effective when participants share common interests, and social bonds such as friendship” (2004, 329), and although virtual town meetings clearly possess these “common interests” and “social bonds,” they also adhere to Mansbridge’s dictum regarding adversarial democracy:

If there is no solution that serves everyone’s interest, more debate will not usually produce agreement, and it is often better to cut short a potentially bitter debate with a vote (1983, x-xi).

This is when a virtual town meeting moderator can accept a motion to “call the question.”

Thompson lists the empirical conditions that are necessary for good deliberation (2008, 509). He emphasizes that publicity (the requirement that the deliberative forum be open to scrutiny by citizens either directly or through the media) is vital (2008, 510). Virtual town meeting has, as a by-product, that it facilitates public scrutiny. Johnson, though, sounds cautionary notes. His careful argument for deliberation presents the important caveats that we must:

-

- avoid being utopian;

- not categorically exclude self-interest claims and the resultant conflicts;[10]

- encourage communications to minimize devolution to bad outcomes; and

- recognize that the structure of the deliberative forum affects success. (1998, 173-177).

It would appear that virtual town meeting is consistent with Johnson’s warnings. What is interesting about town meeting is that, even when proposals are primarily self-interested, the town meeting forum makes it necessary to couch the rationale in “common good” terms.

An aspect of public deliberation that has important consequences in the long run is the quality of the deliberation;[11] while quality of deliberation is an aspect of virtual town meetings that is worthy of future study, I will not address quality of deliberation in this study owing to the need for much more data[12]. Steiner et al. have made an important contribution to this subfield by establishing a Discourse Quality Index (DQI) along with examples of how to operationalize the DQI for analytical purposes. The DQI[13] constituents are:

-

- Participation: ……………….…Ability to participate freely in the debate.

- Level of justification: ………..Completeness of presented position rationale.

- Content of justification: …..…Location on the narrow interest to common good axis.

- Respect: ………………………..Do negative statements imply no respect, neutrality or disrespect?

- Constructive politics: ………..Is position strategic, an alternative or a proposed mediation? (2004 56-60)

Studies

Measuring the effects of participation in deliberative democracy has engaged the interest of several political science scholars.[14] Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs (2003) summarize their own look at (what they call) discursive participation surveys:

-

- 4% of the adult public reported on having participated in on-line forums on public issues in the past year.

- 24% had engaged in Internet or instant-message conversations about such issues.

- 25% had attended a meeting to discuss such issues.

- 31% had tried to persuade someone how to vote.

- 47% had tried to persuade someone to alter their point of view on a public issue.

- 68% had face-to-face or phone conversations about public issues at least a few times per month.

Putting Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s opinions (2003) in perspective, Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs found that:

-

- 19% of adults had not engaged in any of the (above listed) discursive activities in the past year.

- 1% had engaged in all six (above listed) activities.

- 58% had engaged in two or more of the (above listed) activities.

- 36% had engaged in three or more of the (above listed) activities.

Considering these results in the context of attempting to increase town meeting participation by a few percent of the total number of eligible voters, leads me to conclude that the goals of virtual town meeting are achievable.

Mutz, in trying to narrow empirical deliberative democracy research, attempts to break out the constituent parts of deliberative democracy and the theorized benefits into separable “middle-range” approaches to deliberative hypotheses (2008, 530):

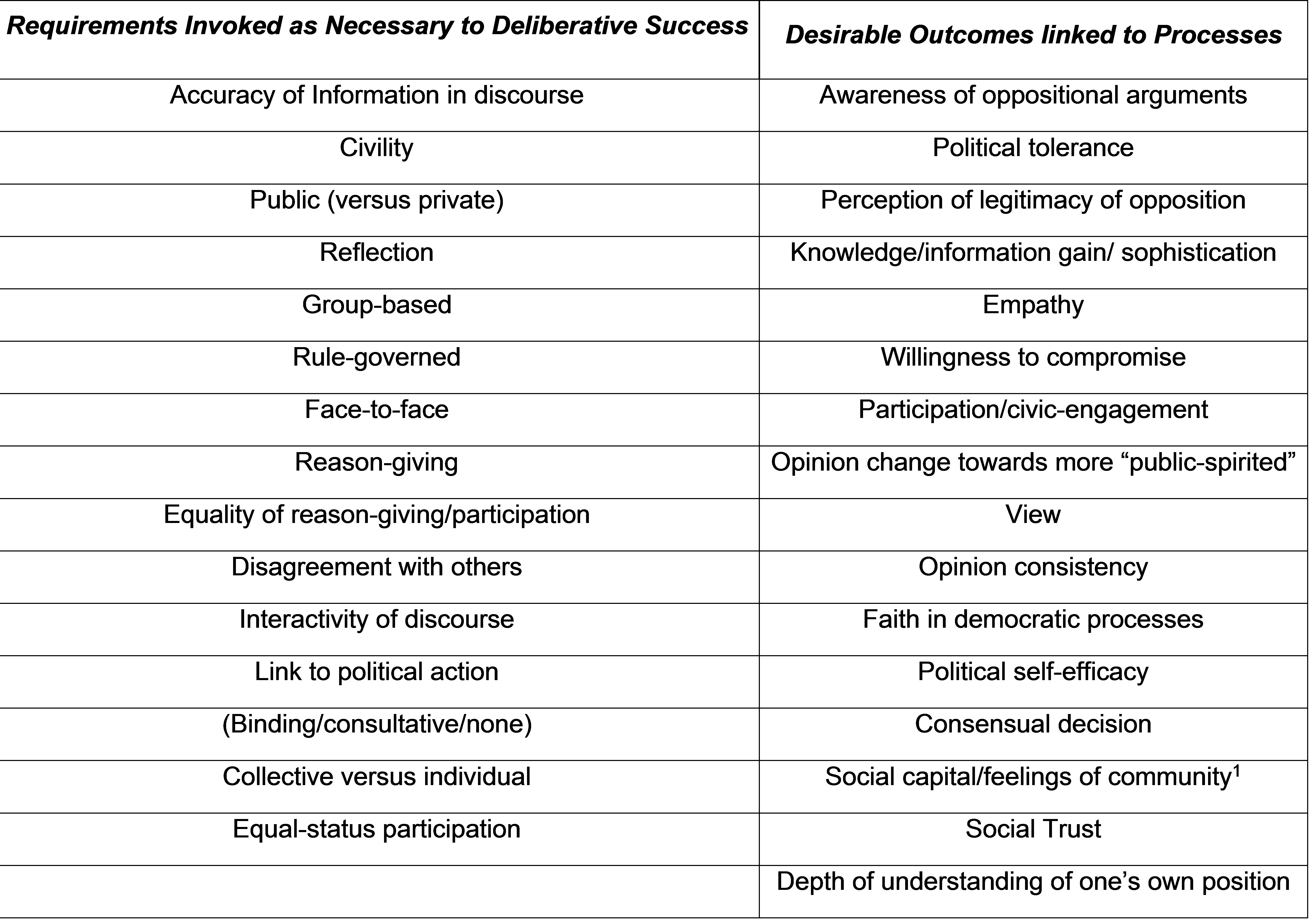

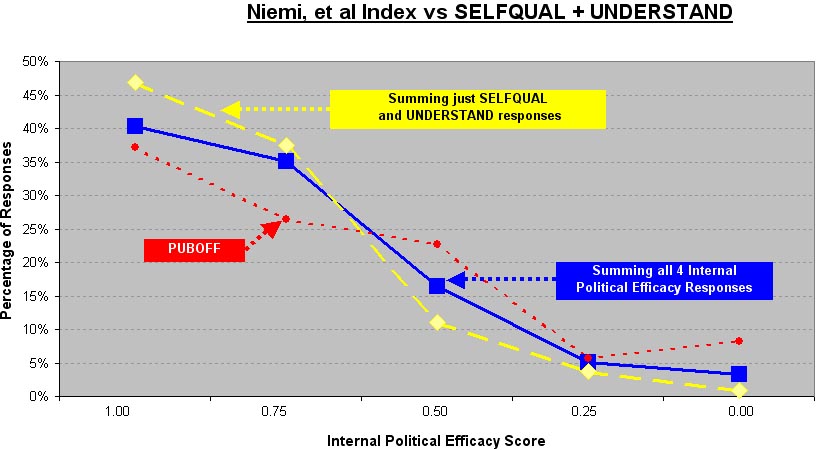

Figure 2-1: Mutz’s Requirements and Outcomes

The requirements of the left-hand column are mostly inherent in virtual town meeting. The accuracy of the information provided is not assured, but the participation of different interests is likely to question dubious information. Maintaining civility is one of the moderator’s duties. Virtual town meeting is public, group-based, face-to-face (plus cablecasting, webcasting and email), has equality of participation, often has disagreement with others, there is interactivity of discourse, a direct link to political action, it is binding, collective and has equal-status participation. The moderator is supposed to ensure reflection by summarizing the issues that have been raised prior to the start of voting. The right-hand column of Mutz’s table defines the desirable outcomes (most of which fall under the heading of political efficacy, discussed below); many of them are the targets of the case study survey questions. Consensual decisions are not a necessity in a virtual town meeting, and may not be desirable in all cases, as pointed out by Mansbridge. It is also not clear that it is possible to separate out the individual items in Mutz’s list in real-world virtual town meetings. Mutz is careful to point out:

The theories and evidence [that she reviewed] do not speak to whether deliberation itself is feasible, but rather to whether, even if they do manage to coax it into existence, its consequences are likely to be as advertised (2008, 533).

Her doubts about feasibility imply that she has not considered town meeting as a form of deliberative democracy. When virtual town meeting is coaxed into widespread existence, an object of future studies will be to measure at least some of consequences that have been theorized, although not advertised.[16]

Mutz is rightly concerned that, despite the “enthusiasm for deliberation” in current political science: “one would expect to know far more about when and why it works well to produce various outcomes” (2008, 535). Virtual town meeting aims to address this issue; however, it is not a test in which we can manipulate variables to ascertain the effect of that variable with all other variables held constant. Mutz has concerns with some proposed experiments about the need for too many necessary and sufficient conditions, which are each insufficiently well-specified concepts. She is also concerned about a lack of specification of the relationships among the parts comprising the deliberative whole (2008, 536). Meeting all of Mutz’s concerns is clearly beyond the scope of this study. Mutz also expresses a further concern that:

Attention has now turned to large-scale institutional implementations of deliberative practices… [T]hey are designed to spread an already accepted practice as widely as possible. I think this kind of action is premature. (2008, 536)[17]

I agree. I do not believe that the virtual town meeting test and its associated case study fall into this category but, instead, believe that they are in line with Mutz’s suggestions.

By contrast, Thompson[18] introduces his review of deliberative and participatory democracy by giving his perspective on the essence of deliberative democracy:

At the core of all theories of deliberative democracy is what may be called a reason-giving requirement. Citizens and their representatives are expected to justify the laws they would impose on one another by giving reasons for their political claims and responding to others’ reasons in return. (2008, 498)

Like Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs and Mutz, Thompson believes that:

[E]mpirical research … findings are mixed or inconclusive …the main reason for the mixed results is that the success or failure of deliberation depends so much on its context…. If only theorists can identify the right conditions, they can confidently continue to extol the virtues of deliberative democracy. (2004, 499-500)

It is the goal of the virtual town meeting research to provide the context in which limited empirical conclusions can be fairly drawn without concern for artificial settings, non-representative groups or manufactured incentives, and it should address Thompson’s fears that “the conditions under which deliberative democracy thrives may be quite rare and difficult to achieve” (2004, 500). Thompson further itemizes three methodological problems that need to be addressed, each of which he then goes on to discuss in detail (2004, 500):

-

- Distinguishing the analytical elements of deliberation- its concept, standards and conditions.

- Structural criteria: recognizing that the conditions that promote some values of deliberative democracy may undermine other values.

- Examining the relationship between deliberative and non-deliberative practices in the political system as a whole and over time.

Connecticut town meeting, both because of its long history and the rules established by State statute, is an approach that meets Thompson’s elements concern that “better are those approaches that distinguish the definition from the evaluation of deliberation [the unit of analysis from the democratic quality]” (2008, 501). He goes on to break down the elements of deliberation analysis into (1) the conceptual criteria, (2) evaluative standards and (3) empirical conditions. Similar to Mutz, Thompson lists necessary conditions for effective deliberation as: a state of disagreement—virtual town meeting at least requires action to which all may or may not agree; a collective decision—a characteristic inherent in virtual town meeting; and the legitimacy of the decision—virtual town meeting has the legal legislative responsibility.

Thompson lists some “standards” that should be used to evaluate the success of deliberative discourse, including public-spiritedness, equal respect, common good, information quality, finding common ground, and equality of participation (2004, 506). He adds the caution that “one of the most consistent empirical findings is that unless special measures are taken, membership and participation are likely to be significantly unequal” (2008, 506). For the set of all eligible voters in a town meeting form of government, this warning is applicable. Participation in town meeting (standard or virtual) is voluntary. Only the willing will participate. The virtual town meeting test is designed to evaluate whether more eligible voters will participate and the case study is designed to measure what, if any, political efficacy effects are produced by making town meeting participation available to a larger group of electors.[19]

Dissemination

Because it is widely felt that participation by citizens in the workings of government beyond the periodic casting of votes is essential for our democracy, many proposals have been put forward to produce greater participation in deliberative democracy. Thompson suggests spreading participation by posing ways of re-structuring deliberation (2008, 514):

-

- Distributed deliberation- spreading functions over different institutions.

- Decentralized deliberation- having several groups deliberate.

- Iterated deliberation—splitting between policy reviewers and policy implementers.[20]

All of these structures are aimed at breaking up the task amongst more manageable groups. Since virtual town meeting is manageable, unless many hundreds of people want to actively participate in the deliberation, none of these structures is applicable to the town meeting legislative function.

One of the best-known attempts at dissemination is Fishkin’s Deliberative Polling. Fishkin describes his suggestion for disseminating deliberative democracy as follows:

The idea is simple. Take a national random sample of the electorate and transport those people from all over the country to a single place. Immerse the sample in the issues, with carefully balanced briefing materials, with intensive discussions in small groups, and with the chance to question competing experts and politicians. At the end of several days of working through the issues face-to-face, poll the participants in detail. (1995, 162)

Referring to Fishkin’s deliberative polls, Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs conclude that not all responses to the deliberative poll have been positive. The durability of changes in attitudes, opinions and knowledge, and the practicality of the design as a means of increasing deliberation among the larger population have been challenged (2004, 334).

Virtual town meeting does not aim to include all of the public in the participatory deliberation process. Rather it aims to reduce the costs in the electors’ cost benefit ratio by eliminating obstacles to participation and by permitting tentative participants to contribute to the deliberation under less threatening conditions. As Wolfsfeld states:

Potential participants consider both the likelihood of success as well as the value of such success when deciding both if and how to act… The final decision, however, is most accurately explained by their own individual cost-benefit analysis. (1986, 125)

Another thread that is prominent in the literature is that technology can play a role in facilitating participatory democracy. Deliberative Polling, Deliberation Day and Citizen Assemblies are examples. Virtual town meeting applies very mundane technology (cable television, webcasting and email) to permit willing participants to participate remotely.[21] There are many current attempts to use technology as a way of enhancing deliberation and participation that are much more ambitious than virtual town meeting. Fishkin (1995), Gastil (2000), Fung (2007a) and Cohen (1998) are some of the leaders in the field.

Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs raise the question: “Can online deliberation capture the experience and benefits of the face-to-face ideal” (2004, 335)? They quote Iyengar (2003) as saying that it produces “roughly parallel results.” Barber’s fear that technology would focus only on defense and profitable commerce has not come to pass (1998, 80). Gastil, in discussing the technology of computer-mediated deliberation, draws the conclusions that:

-

- Face-to-face may be more appropriate in the political arena.

- Political deliberation usually involves diverse and unacquainted participants.

- Computer-mediation can reduce the independent influence of social status (2000, 359).

Also, on the technology front, Shane and his associates have developed software they call “Delibra” (2007). It allows a networked group to communicate with audio and text; participants see themselves depicted around a conference table. Those who wish to speak press a button and are put in the queue. Meanwhile, they are able to ask questions and register responses with text messaging. Virtual town meeting differs from this kind of online participation in that the remote participants “see” the physical town meeting, can verify that their email inputs to the deliberation are displayed and/or read to all participants, and get feedback on the results of their votes. They feel like they are part of the town meeting. It may not be exactly like face-to-face deliberation, but it is certainly better than just watching or just reading about the results in the newspaper.

E-voting, as a substitute for in-person voting and mail-in voting, is practiced in Geneva, Switzerland. Chevallier (2009) has reported on the effects of this form of voting on the turnout at elections and found that it eliminates some of the “invisible barriers” to participation. [22] The techniques used by the Canton of Geneva to ensure the security of the electronic voting procedures are similar in outline to those used in the virtual town meeting.

Political Efficacy

The literature that addresses political efficacy includes one or more of the following topics: (1) definition of the concept; (2) measuring its level; (3) some generalized results; and (4) potential pitfalls in its evaluation. Political efficacy is a relatively new term but not a new concept, with a current consensus as to what the term means and fair agreement on how the concept can be measured through surveys. Wollman and Stouder define the most general forms of efficacy as follows: “Personal efficacy relates to the belief that one can personally affect events, whereas societal efficacy relates to the belief that people in general can affect events” (2001, 562). Thompson lists the items he believes should be included as constituents of political efficacy: (1) increase in political knowledge, (2) political views of other participants and their reasons for holding those views, and (3) the sense of the legitimacy of the outcome (2008, 507). The term ‘political efficacy’ was defined by Campbell, Gurin and Miller as:

“the feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process, … the feeling that political and social change is possible, and that the individual citizen can play a part in bringing about this change” (1954, 187).

In the current political science literature a distinction is made between internal and external political efficacy. Acock defines the distinction as: “[I]nternal efficacy indicates individuals’ self-perception that they are capable of understanding politics and competent to participate in political acts…external efficacy measures expressed beliefs about political institutions” (1985, 1064). Niemi, Craig and Mattei developed and refined the internal and external political efficacy questions adopted by the NES and used by many scholars. Their four internal efficacy survey questions are (1991, 1408):

-

- I consider myself to be well qualified to participate in politics.

- I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of the important political issues facing our country.

- I feel that I could do as good a job in public office as most other people.

- I think that I am better informed about politics and government than most people.

The three external efficacy survey questions are:

The exact wording of these standard NES questions about both internal and external political efficacy are not directly suitable for the virtual town meeting case study because they do not specifically relate to the participation in town meetings. Instead, the survey questions in the case study are tailored to political efficacy in the context of the virtual town meeting and local government considerations.[25]

With regard to the correlation of political efficacy with other characteristics of citizens, Finkel reports that voting and campaign participation had external efficacy effects but little internal efficacy effect (1985, 907). Michelson believes that regional and cultural differences provide different efficacy responses (2000, 147). Morrell reports that, based on his analysis of several data sources, “Internal efficacy relates strongly to psychological involvement; moderately to participation, education, and external efficacy; and not at all to political trust” (2003, 597).

The difference between participating in a town meeting deliberation and merely voting in a referendum may have a different political efficacy effect on electors. In his own experimental study, Morrell concludes that citizens who engage in face-to-face deliberative decision-making, rather than just thinking about and voting on issues, will likely have higher levels of internal political efficacy in those specific face-to-face venues (2005, 63). Iyengar believes that, unlike political trust, the sense of external political efficacy does not appear to be closely intertwined with evaluation of the incumbent government: “Subjective efficacy is not a fleeting response to current political realities but is instead a more firmly embedded attitude concerning the responsiveness of the regime” (1980, 155). Attaining increased political efficacy can be considered as a form of education, or at least, the diminution of ignorance. It may increase or decrease the perception of the quality of governance being provided but it surely increases “individuals’ self-perception that they are capable of understanding politics and competent to participate in political acts” (Acock 1985, 1064).

Caution in the process of evaluating political efficacy is a common thread that runs through the writings of Delli Carpini, Shapiro, Thompson and Mutz. The questions used to measure it are indirect, open to varied interpretation, sometimes misread and limited by the choices of answers available to respondents. Reading too much into the statistical analysis of political efficacy surveys is discouraged. By contrast, Rosenstone and Hansen present (without reference) very precise numbers about the benefits of political efficacy (2003, 79):

-

- People who feel a sense of personal competence to figure out what is going on in local politics are 5.4 percent more likely to attend local meetings.

- People who believe that their actions will affect what local government does are 3.2 percent more likely to attend.

- Likewise, people who believe that their actions will make the government respond are 5.7 percent more likely to write to public officials.

- 2 percent are more likely to sign petitions.

Conclusions Drawn From The Literature

The primary conclusion I draw from this review of the political efficacy, participatory and deliberative democracy literature is that it appears that virtual town meeting could provide a laboratory for empirical testing of the underlying political theories about deliberation and participation and their combined effect on political efficacy. My hypothesis that virtual town meeting has some positive effects on political efficacy is neither denied nor strongly supported by the data that has been collected to date, but the results do provide some useful empirical data.

The virtual town meeting setting appears to meet all of the structural criteria for meaningful testing of deliberative and participatory democracy theories put forth by Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs, Thompson, and Mutz. It is a natural setting, with voluntary participation in a civic duty that has real consequences for the participants. Virtual town meeting can provide the deliberative and participatory quality that is essential for the generation of good empirical data.

The most useful part of the literature is the detailed reviews provided by Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs, Mutz, and Thompson. Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs summarize their findings in five areas:

-

- Americans engage in public talk.

- Social Psychology research indirectly provides support that deliberation can lead to some of the individual and collective benefits postulated by theorists.

- Case studies, surveys and quasi-experiments lead to similar conclusions.

- The Internet may prove a useful tool in increasing opportunities for utility.

- Most importantly, the impact of deliberation is highly context dependent. It depends on the purpose of the deliberation, the subject under discussion, who participates and the connection to authoritative decision makers (2004, 336).[26]

They believe that “we should take great advantage of the myriad real-world deliberative experiments that occur every day” (2004, 335). Virtual town meeting is one such candidate.

Virtual town meeting is a potential way to increase participation in town meeting. A potential by-product of increased participation is that political efficacy may be expanded to cover more citizens. The aim is not to try to extend it to all eligible citizens. If ultimately virtual town meeting is shown to lead to increased political efficacy for the remote participants and/or those who attend, then the question will arise whether the benefits could be made applicable in non-town meeting settings. Fung (b) considers how you would set up Minipublics as a way of implementing town meeting type of forums for participatory deliberative democracy (2007,156). Fung (a) also believes that there should be a comprehensive national system of local assemblies in every rural, suburban and urban place (2007, 450). The advantage of virtual town meeting is that one does not need to invent artificial settings and means in order to analyze participatory deliberative democracy. One may consider the alternative of devolving legislative prerogatives from the States to local municipalities and neighborhoods. Local control of schools, open space planning, police and fire protection, local taxation, local zoning and wetlands preservation are all potentially devolveable to town meeting types of legislative control.

One of the recurrent themes in the literature is caution. One should take small steps, have low expectations and be skeptical of the validity of apparent empirical results. One should also not set expectations too high in that, as Wollman says: “[T]he fact that people in general feel that they can be effective by taking a particular action does not necessarily imply that they will act” (2001,565). A related thread is that some authors appear to consider deliberation and participation as the answer to all of our democratic shortcomings. Sanders somewhat addresses this from her elite perspective:

Average people can be improved in a number of ways through their involvement in politics. Not only might they develop basic competency at citizenship, they also are likely to become better human beings, acquiring both individual autonomy and a sense of common involvement. Many contemporary democrats extend this hope to all citizens: they want everyone involved in politics, but they want everyone to deliberate about it. (1997, 359)

On the positive side of the ledger, virtual town meeting addresses Ryfe’s requirement that “we must learn what deliberation actually looks like… by investigating deliberation in the natural political contexts in which it takes place” (2005, 64).

With regard to the questions raised about how the discipline ought to address deliberative and participatory democracy, Thompson makes the plea (also voiced by Delli Carpini, Cook and Jacobs and Mutz) that:

The division of deliberative labor [between theorists and empiricists] may or may not serve the practice well… But even with the division of labor that is likely to persist, collaboration can still go forward if theorists and empiricists engage with each other’s work…theory and empirical research might then more often progress hand in hand. (2008, 516)

That seems like the hard way to accomplish an important task. Better government is a pragmatic task. [27] Allowing arbitrary field specialization to interfere with progress towards this vital goal seems counterproductive.

I hope that I have made a reasonable case for town meeting as a logical setting to investigate participatory and deliberative democracy. And yet, town meeting is not mentioned at all in most of the literature; when it is mentioned it is either misidentified or mentioned to put Mansbridge’s work in context (without providing any details). Hibbing and Theiss-Morse revile town meetings for their “vitriol” (2003, 241) without referencing their source. And, none of the authors cite either Bryan or Zimmerman, who have written excellent works about town meeting. I find this puzzling, and hope that the report on this field test and case study will underscore their important contributions to participatory and deliberative democracy scholarship.

Chapter 3: The Tests

The objective of increasing town meeting participation coupled with the availability of live cable broadcasting (cablecasting) and citizen’s wide use of email communications led to the initial test of remote live town meeting participation (virtual town meeting) in 2008. Remote participants could watch the proceedings on their television sets and could provide written inputs (comments, questions or points-of-order) and vote via email.

As a precursor to the initiation of virtual town meetings in Salem, my Masters Thesis (Sielman, 2006) investigated whether or not eligible voters who do not currently participate in town meetings would do so if they could participate from home, a business trip, college or while serving in the armed forces. In 2007, based on that survey’s results[28], I proposed virtual town meeting tests to the Salem Board of Selectmen[29]. Included in the presentation to the Board of Selectmen was the Town Attorney’s ruling that a virtual town meeting would be legal in the State of Connecticut based on the Freedom of Information Act which explicitly recognizes that a meeting can take place “by means of electronic equipment”, and Section 1-200 of the General Statutes which grants the Town’s explicit authority to adopt rules of order for the conduct of its meetings, coupled with the State Constitution’s recognition that the people have an undeniable and indefeasible right to alter their form of government in such manner as they may think expedient (Article 1, Section 2). Further, Connecticut General Statute §7-5 says, “the place of holding town meetings may be determined by a majority of the voters present and voting at any town meeting specially warned and held for that purpose”. The Board of Selectmen approved the virtual town meeting tests, provided that there would be no costs[30] to the Town, and brought the matter up at the May 2008 annual town meeting which initially[31] approved three virtual town meetings.

The Application of Electronics

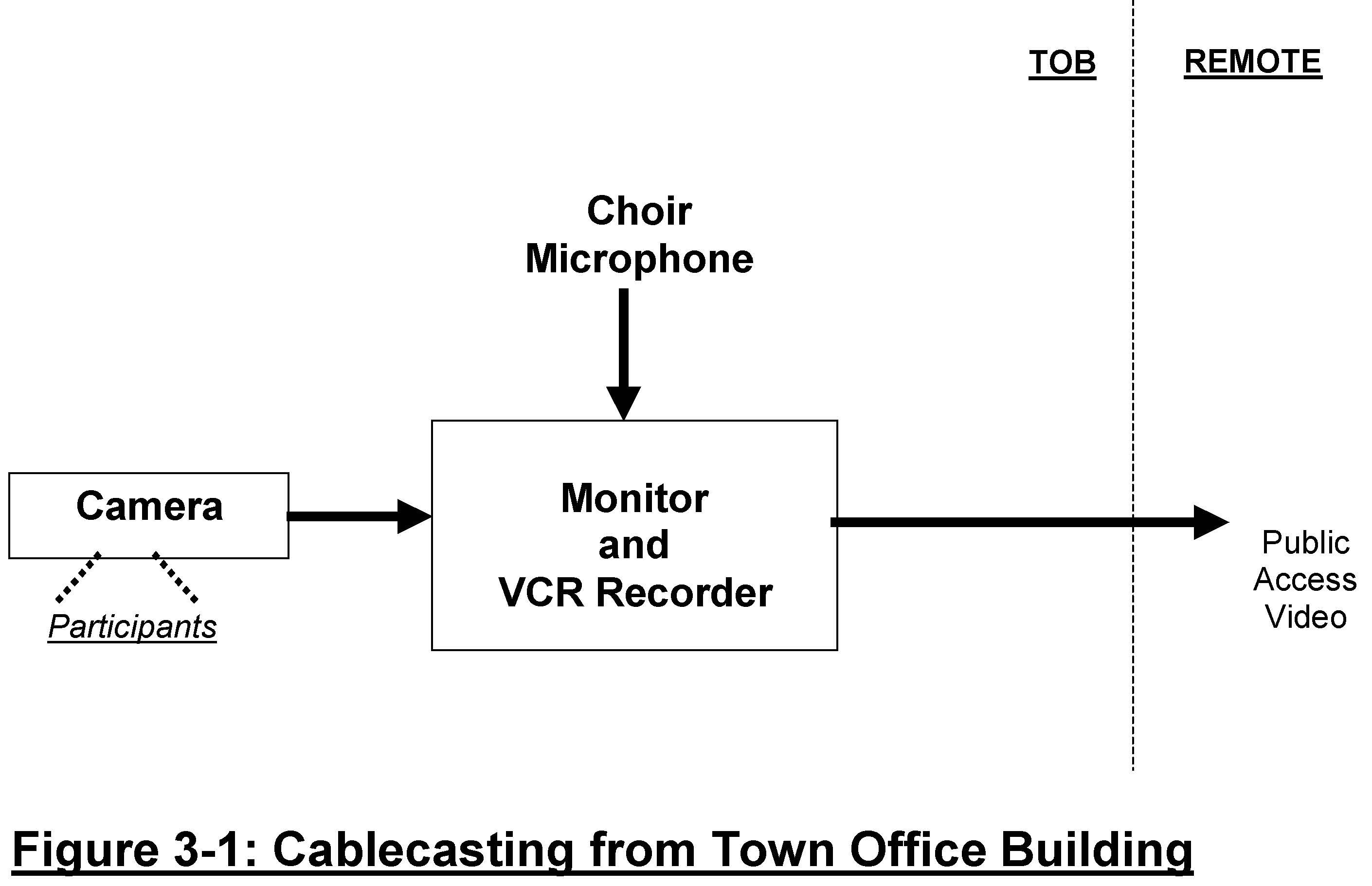

In the period 2001-3 local cable franchises were awarded to cable companies in Connecticut in return for which the cable companies provided studio facilities, equipment and training in the use of video equipment to facilitate public access to locally generated material, including educational and governmental materials. The cable company (Comcast) provided a free video uplink facility (including some electronics) at the Salem Town Office Building (TOB) as part of a party line cable franchise that also includes the towns of East Haddam, Haddam Neck, Lyme, and Old Lyme. The facility in the Salem Town Office Building initially included a choir microphone hung centrally from the ceiling of the large conference room (capacity = 75), a tripod mounted camcorder and a VCR recorder/monitor. This equipment suite is shown schematically in Figure 3-1. With this facility the Town of Salem was able to broadcast, live, town meetings and Board and Commission meetings from the Town Office Building to homes that had signed up for cable service (approximately 60% of Salem households are cable subscribers). These broadcasts have continued to this date.

Figure 3-1: Cablecasting from Town Office Building

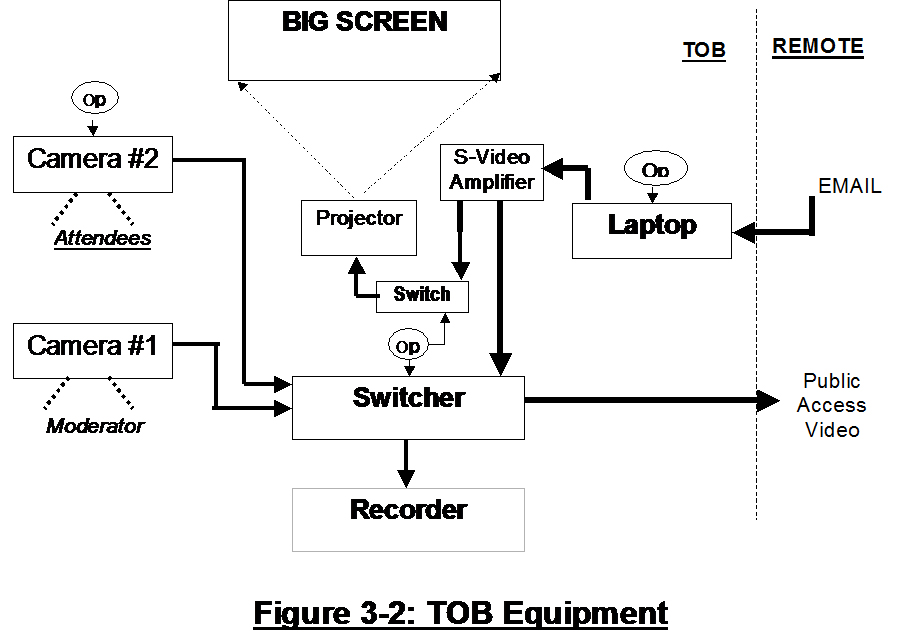

In order to test the feasibility and utility of remote participation in town meetings, the equipment at the Salem Town Office Building was augmented with a second tripod-mounted camcorder (to permit separate video of the moderator and audience participants), a laptop computer equipped to receive email; a large projection screen (to permit audience viewing of spreadsheets/PowerPoint presentations and incoming emails; a second monitor to view all potential video from which the operator can select what to transmit; and a switcher to select moderator the video source for transmission via cable. A second slaved laptop was provided for the to select incoming email messages. This equipment suite is shown schematically in Figure 3-2.

Feedback received from the initial virtual town meetings, based on cable transmission for outgoing video (and audio) and email for incoming questions/comments and votes, highlighted the following shortcomings of the system:

-

- Only 60% of Salem households (that possess cable) could participate.

- Both a computer (~90% of households have computers) and a television set with a cable source were required to participate. Even where both existed in a household, they were often located in different rooms.

- Potential participants away on business trips, away at school or serving in the armed forces could not participate.

Figure 3-2: TOB Equipment

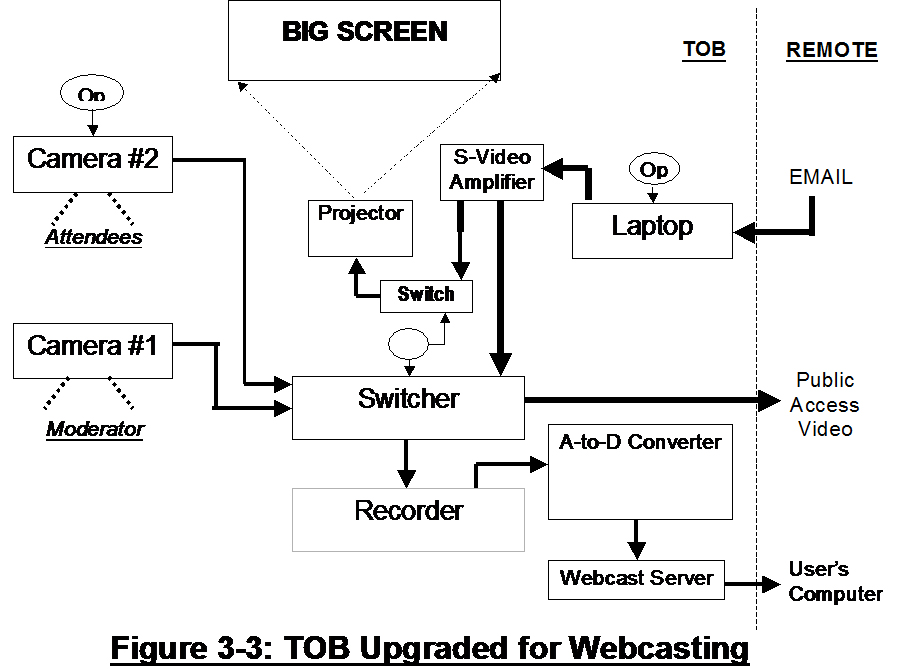

Based on this feedback, it was decided to augment the system by providing webcasting of the video. This entailed the addition of a server for uploading video; a device for converting from analog to digital signal format; some software (Wirecast); and the services of a video provider (Livestream, who provides basic Live and On Demand video free of charge in return for periodic advertisements).

Figure 3-3: TOB Upgraded for Webcasting

This expanded system equipment suite is shown schematically in Figure 3-3. A domain name of www.salemct.org was reserved for the webcasting activities. With both the input (video) and output (email) on a single computer, the popular way to participate remotely is to place both the website and the email software simultaneously on a horizontally split monitor.

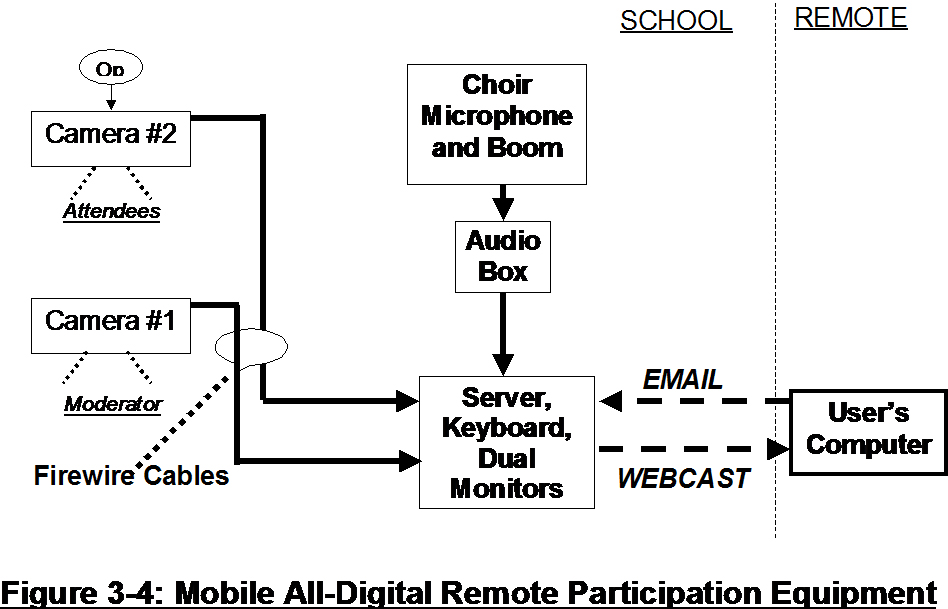

It was further desired by the Board of Selectmen that meetings that are too large for the Town Office Building, and are consequently held at the School or Firehouse, should be capable of being run as virtual town meetings. Since the cable provider (Comcast) set a price of $90,000 for a video feed at the School or Firehouse, it was decided to forego the cable casting and to configure a webcasting-only (outgoing)-email (incoming) virtual town meeting capability at the School. The School is centrally located and is familiar to the many families who have (or had) children that matriculated through it. This all-digital capability is depicted schematically in Figure 3-4.

Figure 3-4: Mobile All-Digital Remote Participation Equipment

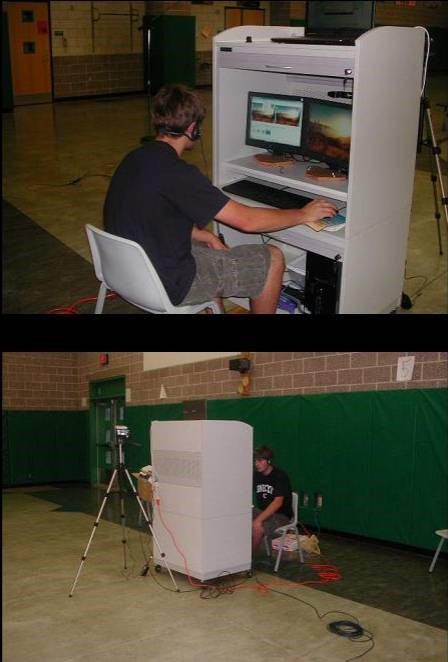

A picture of this mobile facility (capable of being used throughout the school) is shown in Figure 3-5.

A characteristic of the assembly of hardware and software for the virtual town meeting tests was the necessity to provide the equipment without the expenditure of significant funds. Likewise, the operation of the equipment, both during tests and actual virtual town meetings, was dependent on volunteer help[32]. The funding limitations also affected the choice of transmission quality resulting in periodic video dropouts on the webcasting uplink[33]. A further equipment modification is undergoing development because not all of the attendees at town meetings heed the moderator’s exhortation to “stand up and speak up” when asking questions or making comments. As a result they are not always readily understood by the remote participants. An approach that is being developed to address this problem is the use of a parabolic microphone antenna that is slaved to the camcorder which pans to and zooms in on attendees when they are speaking.

Virtual Town Meeting Processes

In addition to the provision of hardware and software to enable virtual town meetings, it has been necessary to develop operational processes. The processes that we have evolved for virtual town meetings are in response to a number of requirements that must be fulfilled if the virtual town meeting is to achieve its goals. Requirements that we have set include:

-

- The system must be easily utilized by those who choose to participate remotely.

- The system must have a minimum adverse impact on those who attend the virtual town meeting in person.

- The system must be protected from fraud by excluding ineligible participants.

- The system must cast out multiple votes from a single validated email address.

- The system must provide transparency so that attendees will be aware of the number of remote participants.

- Since Internet voting inserts a delay (of up to approximately 90 seconds) the votes of attendees and the votes of remote participants must not influence each other through non-simultaneity.

- A record of remote participant inputs must be created and stored.

Easily utilized by remote participants

More than 85% of Salem residents have and use email[34]. That percentage is far greater than the number of voters who can attend an evening meeting on any given date set by the Board of Selectmen. Hence, the use of email in virtual town meeting participation represents a net increase in the potential number of town meeting participants. It does not cover 100% of potential participants but does meet the virtual town meeting goal of increasing town meeting participation. However, if the process is complicated, cumbersome or protracted, new remote participants may fear getting involved. If the system is complex, inexperienced remote participants are likely to make errors and potentially invalidate their vote or prevent their comment or question from being a part of the deliberation process. Therefore, the process that we have evolved is simple, easily understood and requires a minimum of actions on the part of the remote participant.

To simplify the remote participation process and eliminate the need to remember the appropriate e-mail address, the system sends out five emails to each registered participant on the day of the meeting. These blank emails have subject lines that say, respectively:

-

- Present (this email also contains the town meeting agenda)

- Speak

- Point-of-Order

- Yes

- No

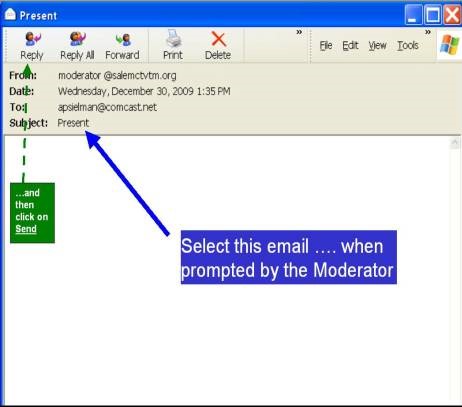

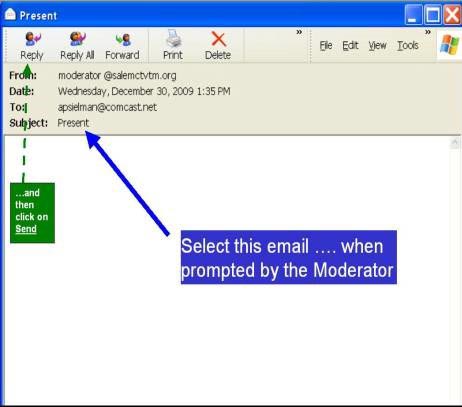

At the beginning of the meeting, the moderator asks all of the remote participants to signify their participation by selecting the Present email and then clicking on “Reply” followed by “Send”. The computer automatically counts the number of remote respondents[35]. The number is displayed on the moderator’s laptop and reported to the attendees by the moderator.

Figure 3-6: Present Email Response

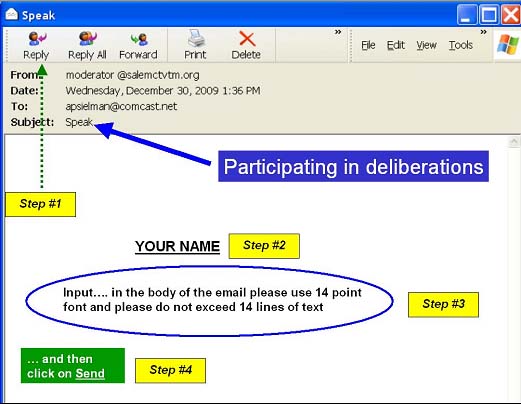

During deliberations, remote participants who wish to submit a comment, question or point-of-order select either the Speak or Point-of-Order email (as appropriate[36]) and then click on “Reply”, type their name and message in the body of the email, and then click on “Send”. The moderator has access to a display (on his laptop) that shows the number and source of remote participants, and uses this information to select inputs to the town meeting.

Figure 3-7: Use of the Speak Email

During virtual town meeting votes, the moderator will instruct remote participants when they should send in their votes. To vote in favor of the current motion, a remote participant selects the Yes email and then clicks on “Reply” followed by “Send”. To vote against the current motion, a remote participant selects the No email and then clicks on “Reply” followed by “Send”. The computer automatically counts the votes[37]. Once both local and remote votes are in, the moderator announces the result. A sample “Yes” vote is shown in Figure 3-8.

Figure 3-8: Email Voting Procedure

Minimum adverse impact on attenders

Inevitably, the moderator’s instructions to remote participants is an added function that non-virtual town meetings do not require and which could be viewed by some as an intrusion on a “traditional” town meeting. This must be weighed against the increased legitimacy of a town meeting that encompasses more participants. As the number of virtual town meetings increases and the number of eligible voters who participate in them increases, the need for detailed instructions for remote participants will diminish. As a general practice, most town meeting moderators instruct attendees on how to cast their vote and what both the ‘yeah’ and ‘nay’ votes mean. With virtual town meetings the moderator provides instructions to remote participants on how to let their virtual presence be known (email Present), how to raise their virtual hands during debates (email Speak or Point-of-Order) and how to vote (email Yes or No)[38].

Protected from fraud

The most frequently asked question about virtual town meetings is: How will you prevent unauthorized voters from voting or even disturbing the deliberation process? In conventional town meetings, unauthorized voting is most frequently predicated on the knowledge of the moderator for voice and show-of-hands voting. At large meetings, moderators will frequently ask those ineligible to vote to identify themselves. In the case of challenges or close vote, citizens can ask for a “checklist and ballot” where a Town official, using the voter registration list, verifies the eligibility of voters who then cast paper ballots[39].

In the case of virtual town meeting, the capabilities offered by the email service provider (Comcast) permit us to restrict incoming emails to a Trusted Address List (TAL). Only those who register their email address and who have been certified to be on the official Town voter registration list have their email address put on the TAL. Therefore, only emails from addresses on the TAL will be received in the Inbox of the virtual town meeting computer. Emails from other email addresses (not part of the Trusted Address List) are funneled into the “Junk Email” folder. This is not a foolproof system- it has been shown that if an individual knows the email address of a member of the TAL, it is possible, with some effort, for that individual to appear to be sending an email from the TAL member. To thwart this possibility, the messages that are sent out on the day of the virtual town meeting are coded. Thus, in effect, the Yes and No emails are individual (reusable) ballots sent only to valid remote participants. Since only legitimate TAL members receive these messages, and only replies with the coding are accepted, fraud has been made less likely.[40]

Cast out multiple votes

The one man- one vote principle is applied by requiring each member of a household that has multiple eligible voters to register a unique email address for each eligible voter. In cases where someone attempts to “stuff the ballot box” with multiple votes, the computer system funnels all of the Yes and No votes into separate folders. The folders are sorted by source, so that multiple votes from a common email source will be contiguous. Duplicated votes are deleted from the count[41].

Transparency

One of the hallmarks of town meeting is that it is a group process where people interact and change their positions based on what they hear there neighbors say. It is therefore important that the virtual town meeting attendees are fully aware of the remote participants and that the remote participants feel “a part of” the meeting. To that end the tests that we have run are based on three potential video outputs (selected, when appropriate, by the operator). One camera is focused on the moderator. A second camera (located near the moderator) is focused on speakers in the audience when they are contributing to the deliberation process. A third video source is the computer that serves the dual purpose of (1) projecting illustrative material (such as spreadsheets or diagrams), and (2) processing email inputs and projecting counts or individual remote participant inputs under the direction of the moderator. Thus, attendees are aware of who is participating remotely, what comments/questions or points-of-order are being made and what the vote tallies are. The remote participants receive the video and audio of the moderator and attendee participants and see the same displays that the local audience sees.

No influence on votes by other group

The Internet is not instantaneous. The time between transmission of an email and its reception varies, but is usually less than 90 seconds. The solution of our moderator has been to instruct remote participants to vote on each motion and wait 90 seconds before having the attendees vote. In this way, the votes of attendees will not influence remote participants. The votes of remote participants are not displayed until so directed by the moderator. Our moderator has used the 90-second interval to provide useful town information to both the attendees and the remote participants[42].

Record of remote participant inputs created

Although official minutes are created by the Secretary of the town meeting (appointed by the moderator at the beginning of the town meeting), these minutes are augmented by the recorded video that was transmitted during the virtual town meeting and by the stored record of all emails received during the meeting[43]. From the point of view of an accurate historical record of town meetings, the virtual town meeting, as we have evolved it, will provide a much richer source.

A further capability is that the video of virtual town meetings is stored on the www.salemct.org website and is available for ON DEMAND replay at any time. As a consequence voters who were not able to participate in the virtual town meeting, live, still have the ability to review it after the fact. This is particularly valuable for questions that must be adjourned to a charter mandated town-wide referendum because it provides an opportunity for referendum voters to educate themselves on the issues prior to casting their referendum vote.

Measurement Of Participation Impact

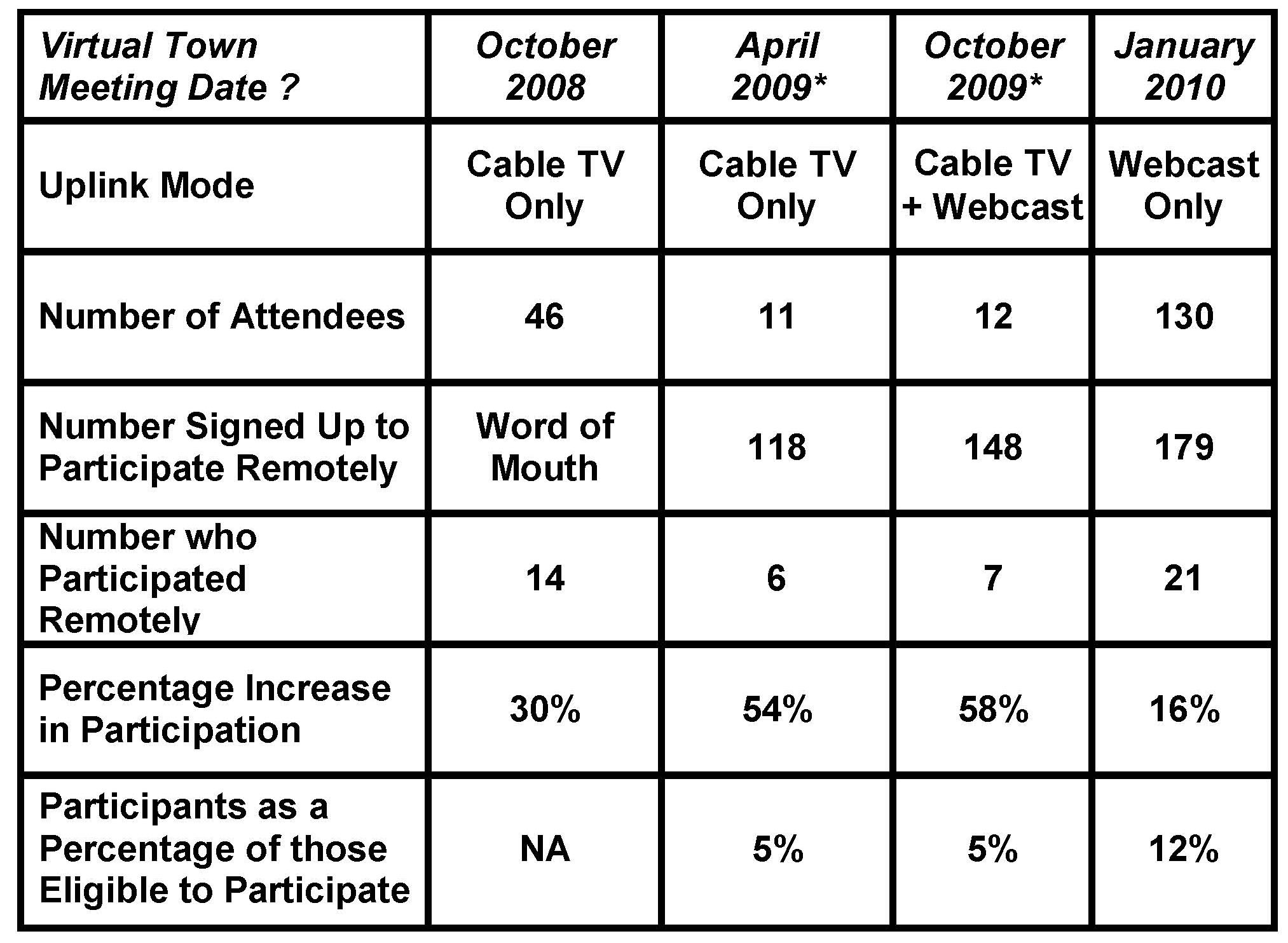

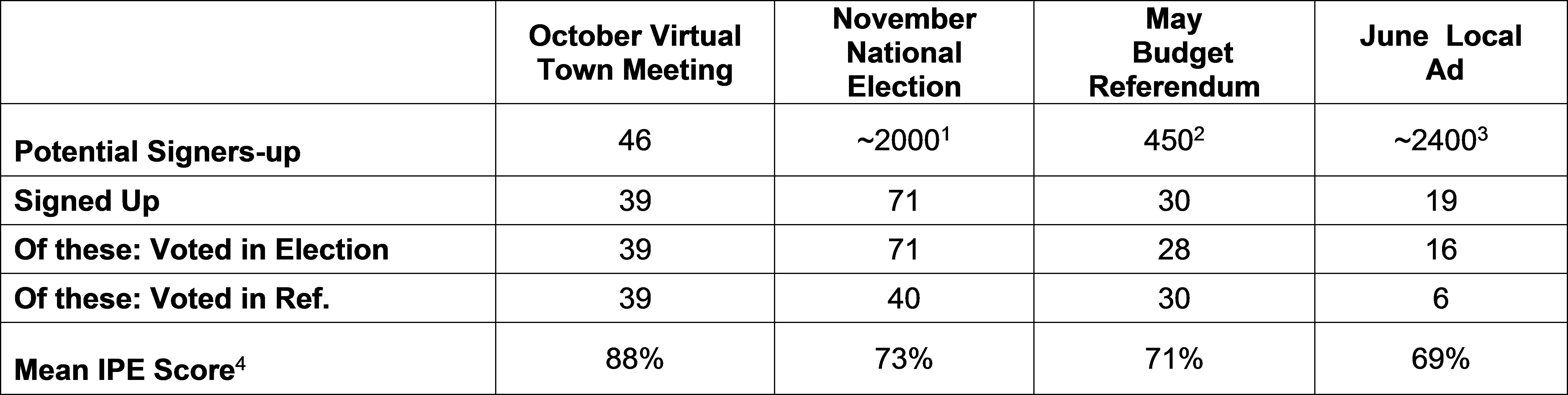

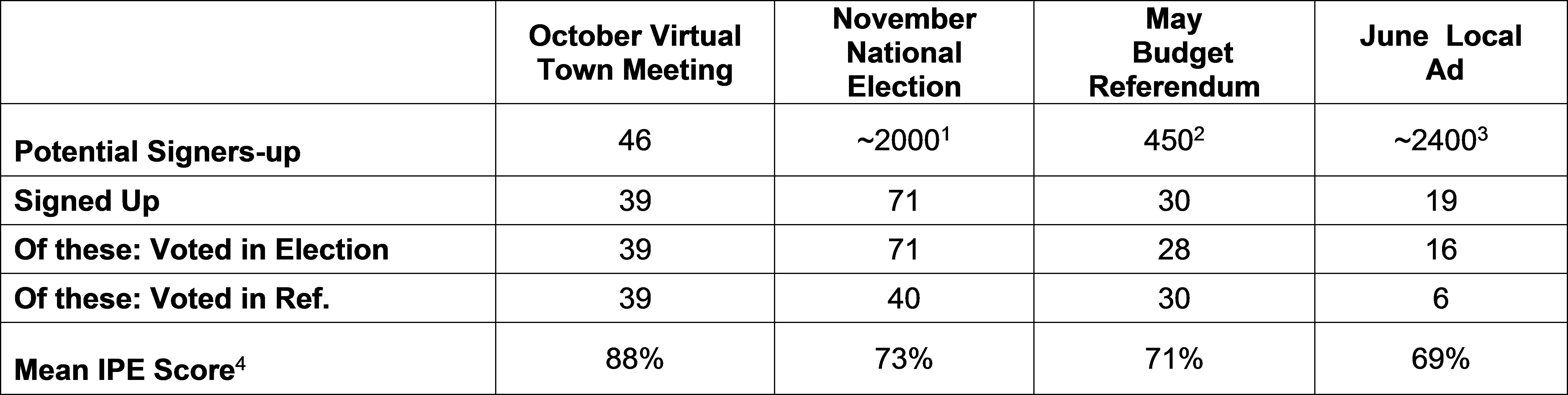

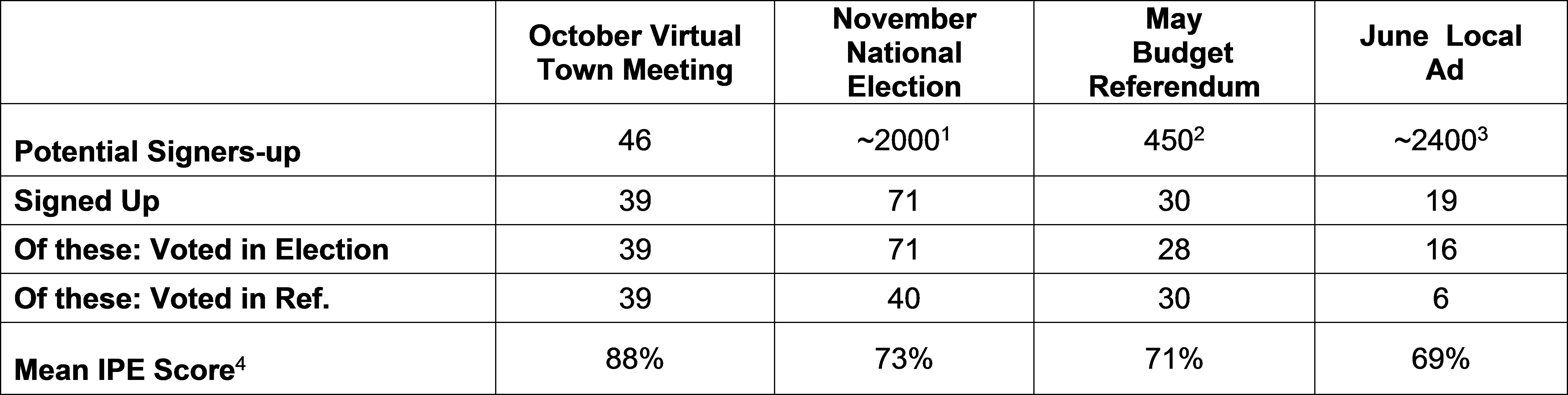

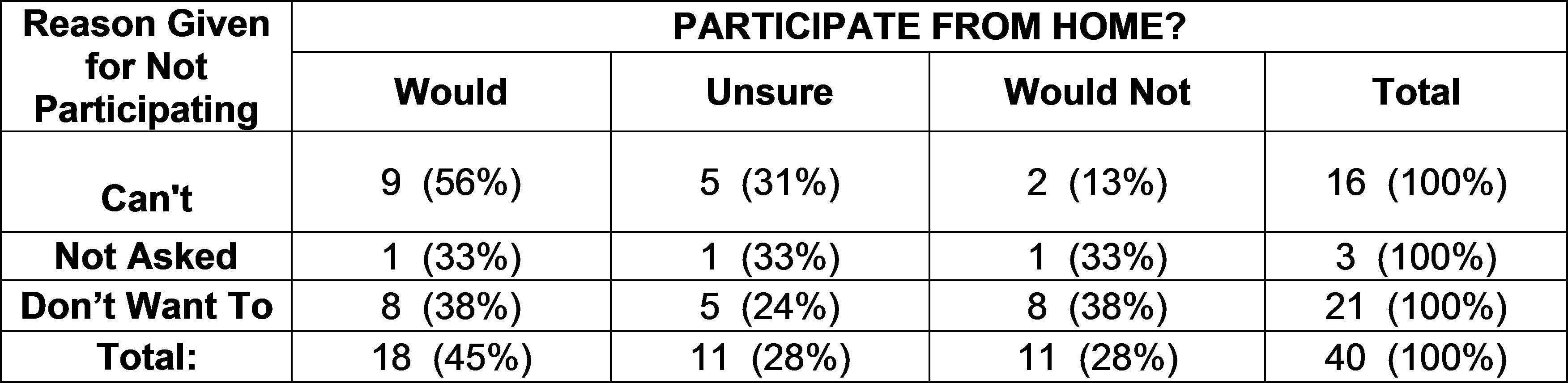

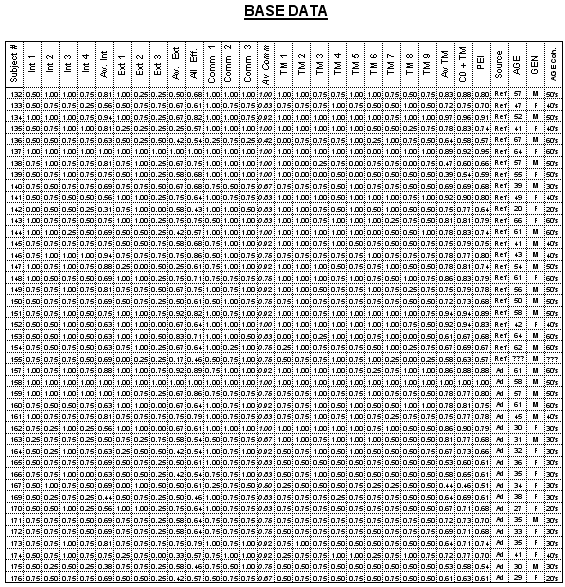

The goal of the virtual town meeting tests was to determine whether the removal of some of the perceived barriers to participation would indeed lead to an increase in participation. Anecdotally, people have emailed me, or said to me, that they participated remotely because they were unable to leave the house on the evening of a virtual town meeting. Figure 3-9 provides a summary of the participation numbers for the first 4 virtual town meetings that have been conducted up to this writing. In the table the third and fourth column titles have asterisks because these virtual town meetings covered only routine matters such as the approval of the sale of an old fire truck upon the delivery of its new replacement.

Figure 3-9: Participation Summary

Of significance in the table is the large number of attendees (130) at the January 2010 virtual town meeting whose call included the approval of further virtual town meetings, the acceptance of a grant and consideration of a major school renovation project. It was the last of these three items that brought out the largest attendance that I have encountered in 22 years of town meeting attendance[44]. Of significance in the third row is the steady, albeit slow, increase in the number of eligible remote participants in virtual town meetings. It is my rough estimate that approximately half of the eligible remote participants attended the January 2010 virtual town meeting. The following row provides the number of remote participants who responded to the moderator’s request to respond to the Present email. From the records of the webpage for the January 2010 virtual town meeting, we know that there were 40 “hits” on the website[45] during the time of the meeting. Some of these we know were non-eligible participants, but some were probably eligible to participate but chose not make their presence known.

The next to last row of the table shows the percentage increase of participation provided by the availability of remote participation. While the percentages for the first three virtual town meetings are larger, the most significant number is the 16% in the last column because the issues at that town meeting were far from mundane. This is reinforced by the last row that shows the percentage those who had signed up to potentially participate remotely that actually did so. Considering that approximately half of the eligible remote participants attended the meeting, one can reasonably double the 12% figure as representing the number of eligible participants who availed themselves of the opportunity to participate remotely.

Conclusions About The Tests

The hardware assembled for the tests of the virtual town meeting appears to work satisfactorily although there are some concerns still about the reliability of the School’s Internet uplink[46]. Clearly, with more available funds the hardware could be improved and the Operator tasks thereby simplified. But it does the job.

The processes that have been developed appear to work sufficiently well to give both the attendees and the remote participants the sense that they are in a common meeting. While the security measures are quite simple they appear to be adequate for the purposes of a town meeting and those participants who have asked about security seem satisfied with the explanations of the measures used. All of the feedback from the January 2010 virtual town meeting is detailed in Appendix C.

Although there has been some local quarterly publication news about virtual town meeting, there has been relatively little effort devoted to increasing the eligible voter enrollment numbers. It seemed prudent to first see if the tests would provide measurable positive results and whether the process and hardware bugs could be overcome, before a major effort to increase enrollment was undertaken. In my estimation, that point has now been reached.

Chapter 4: The Case Study

Overview

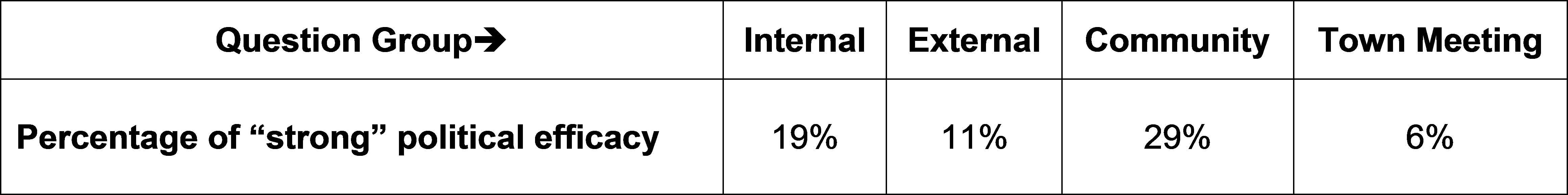

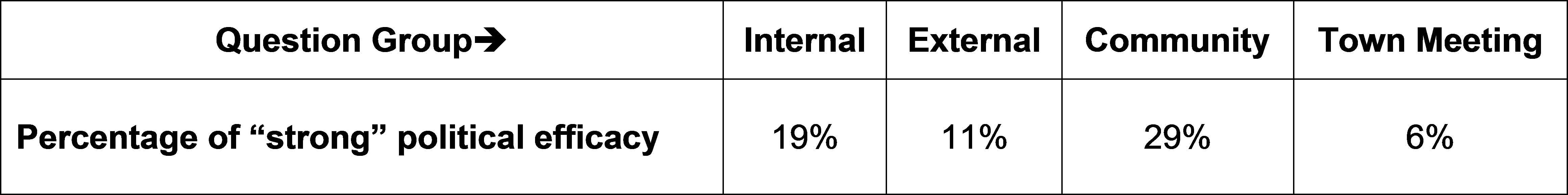

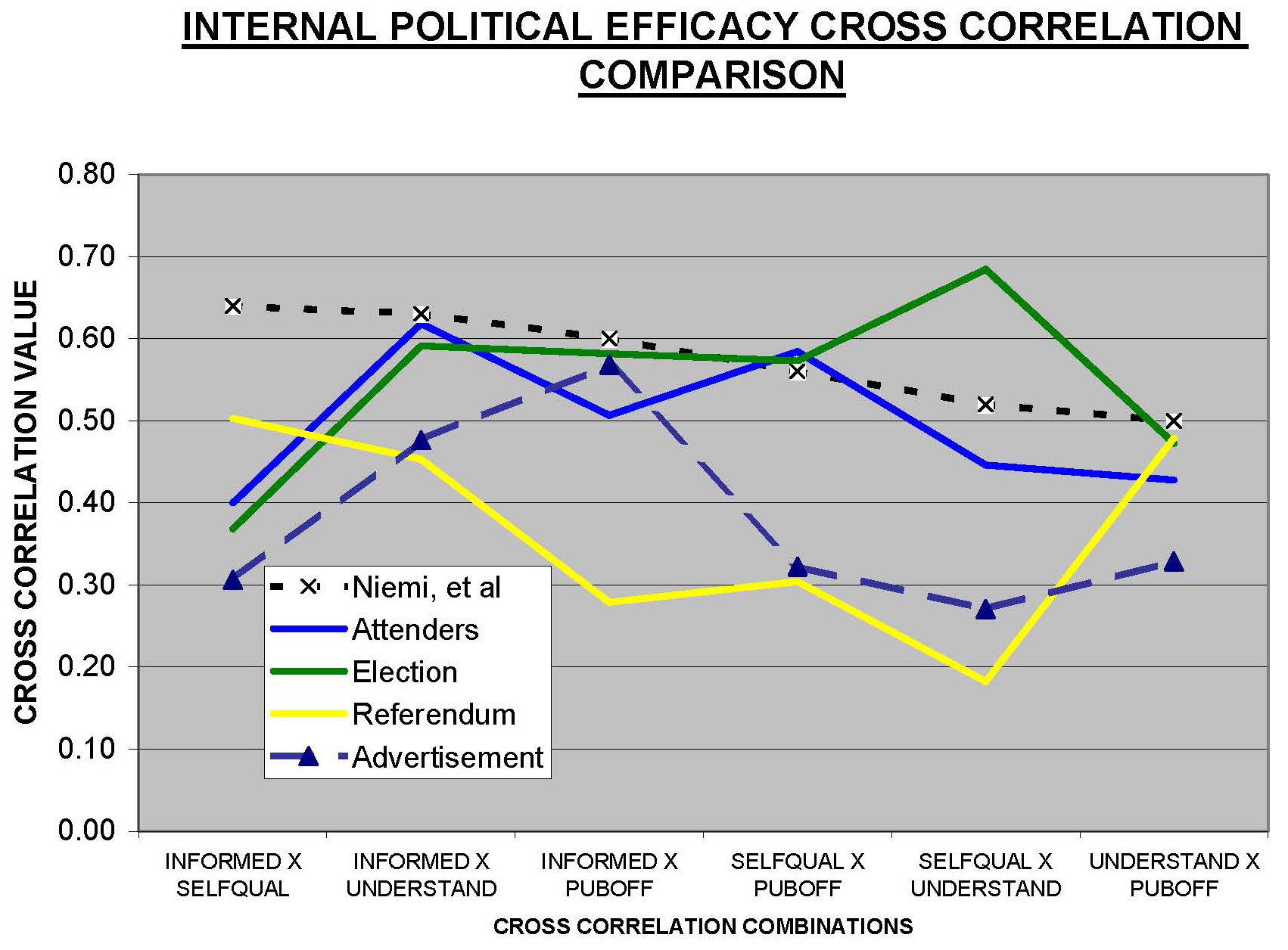

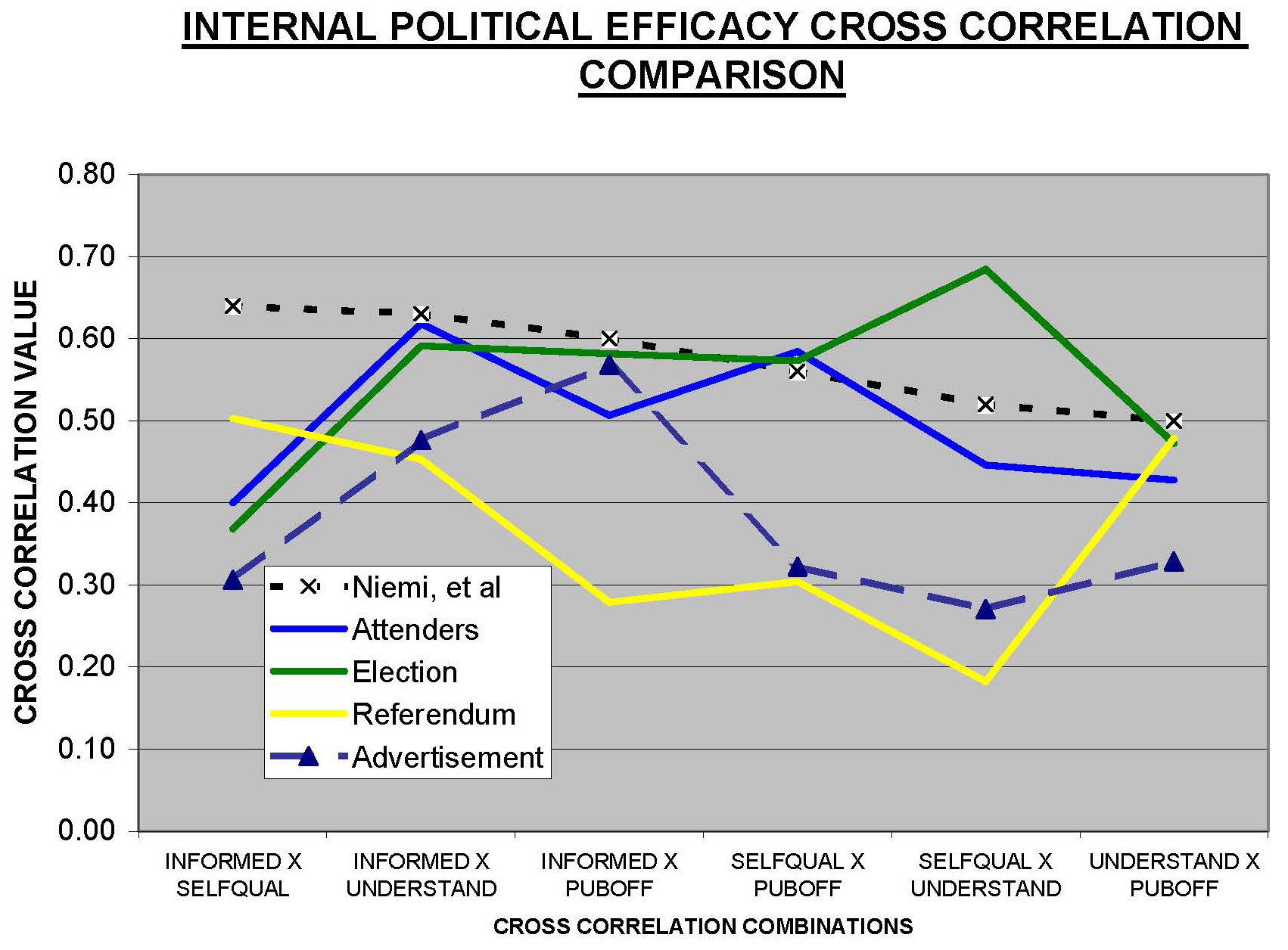

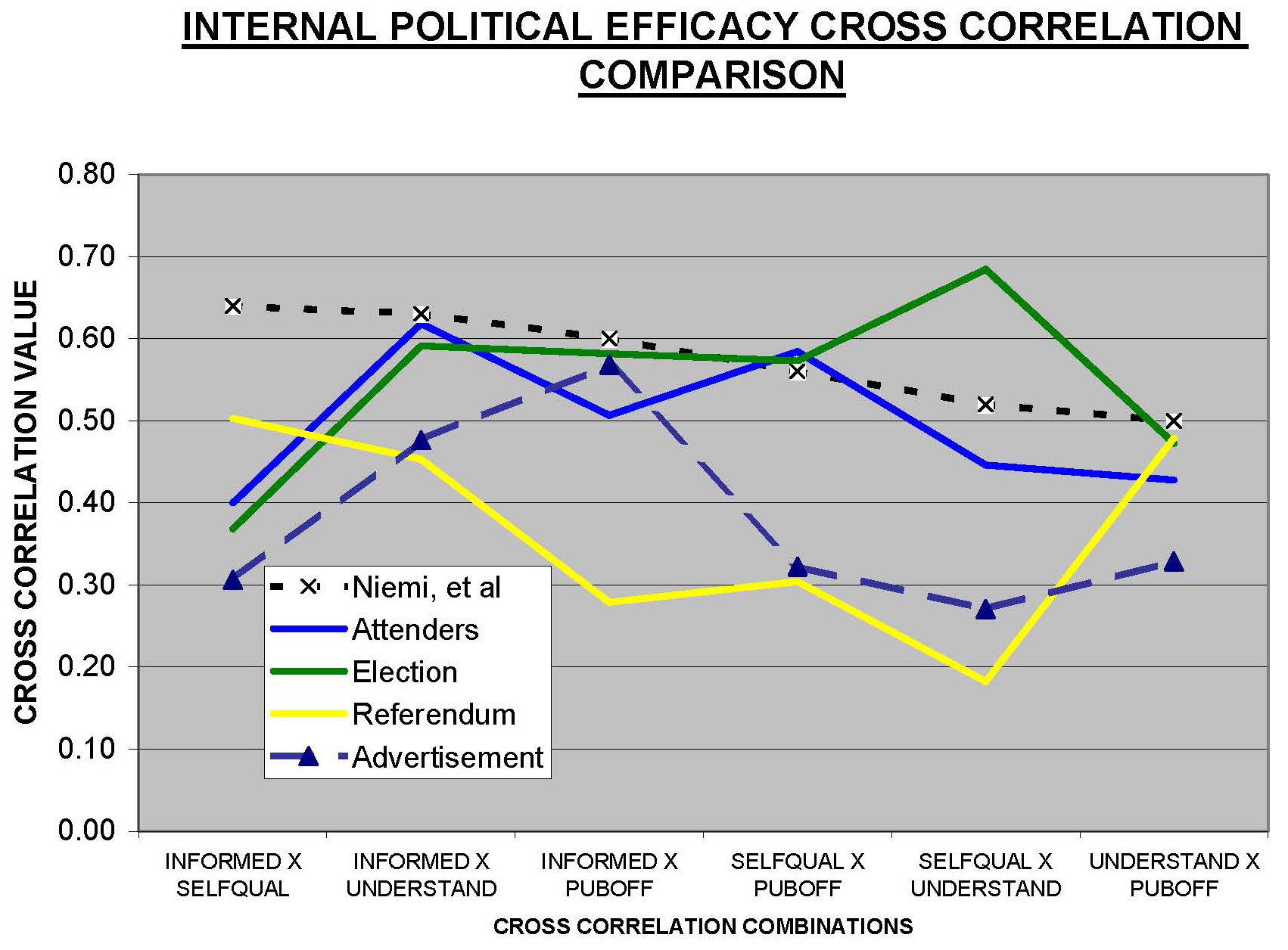

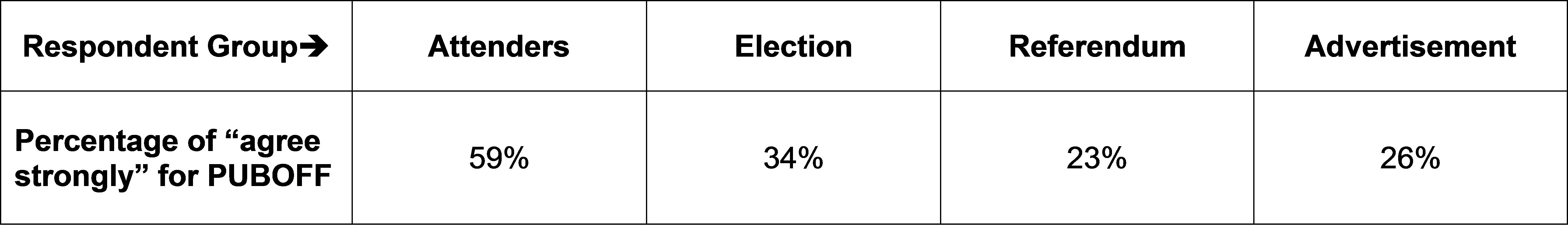

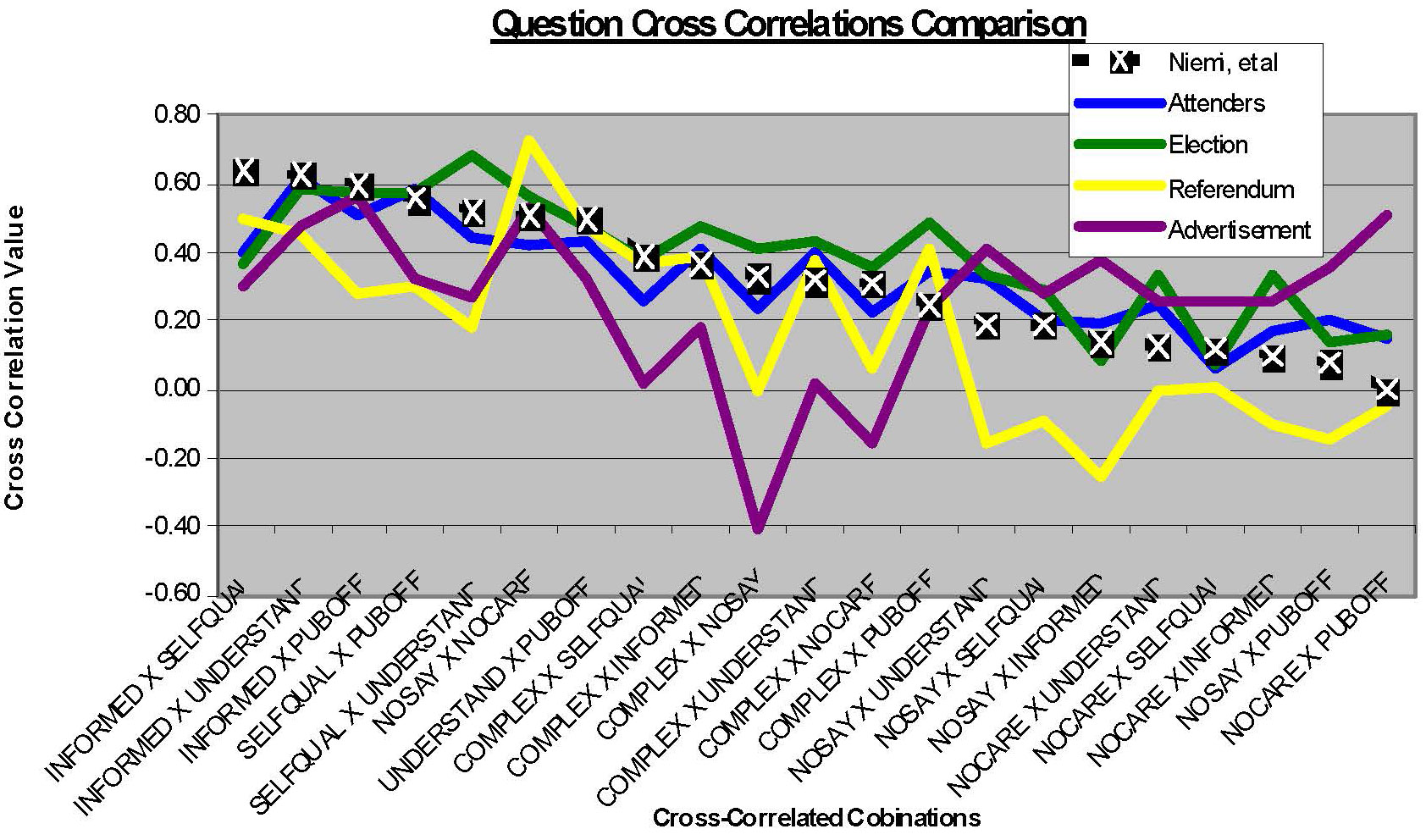

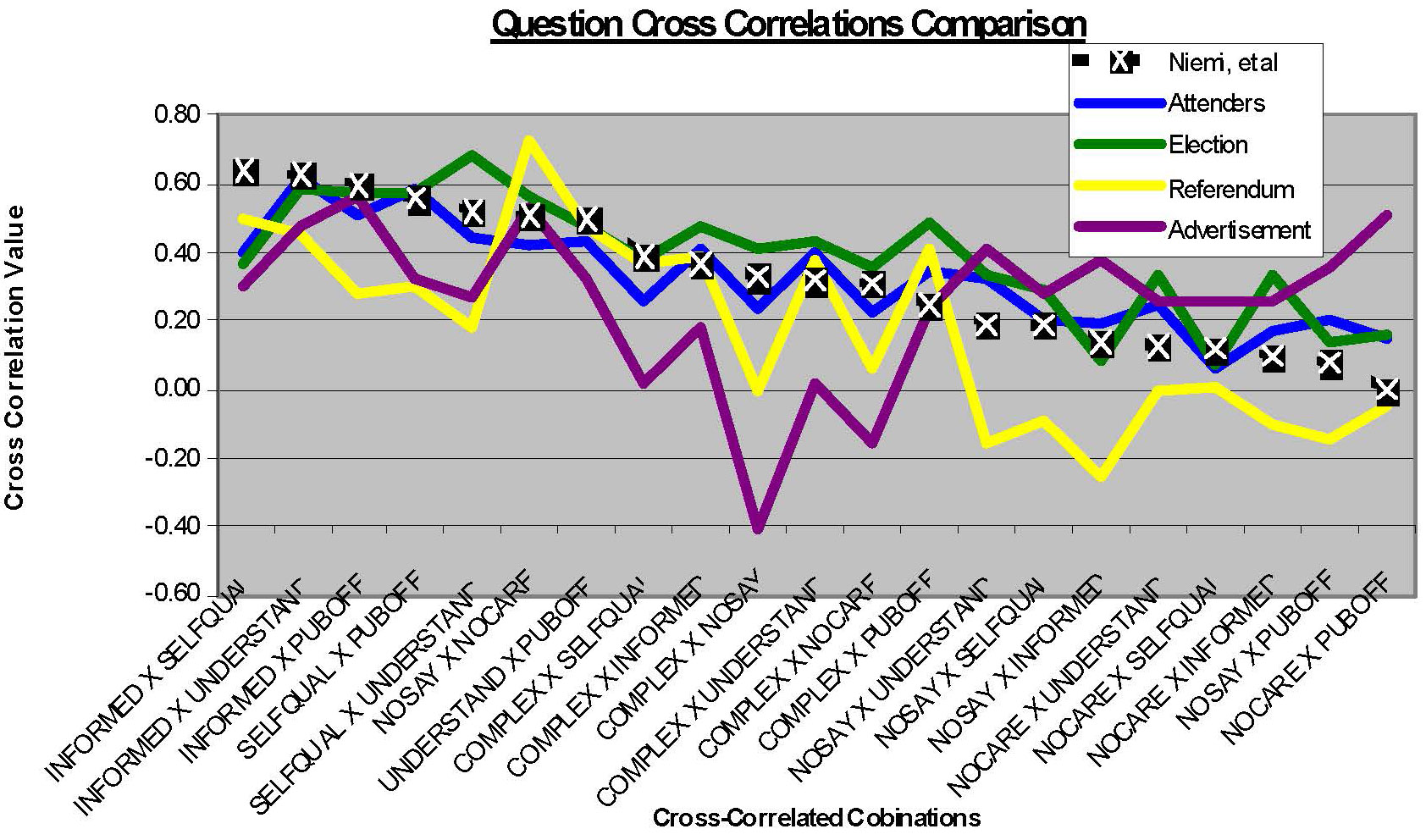

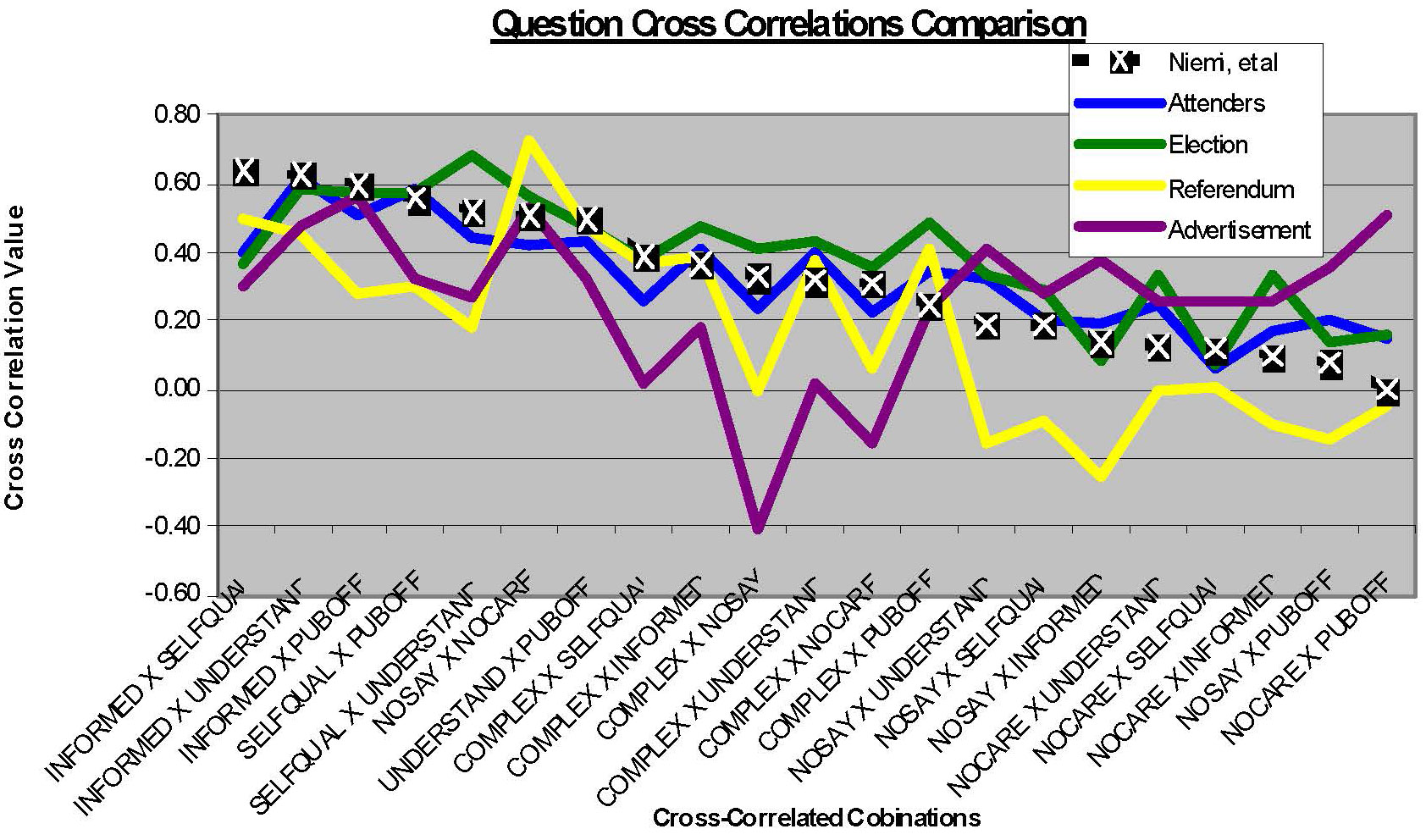

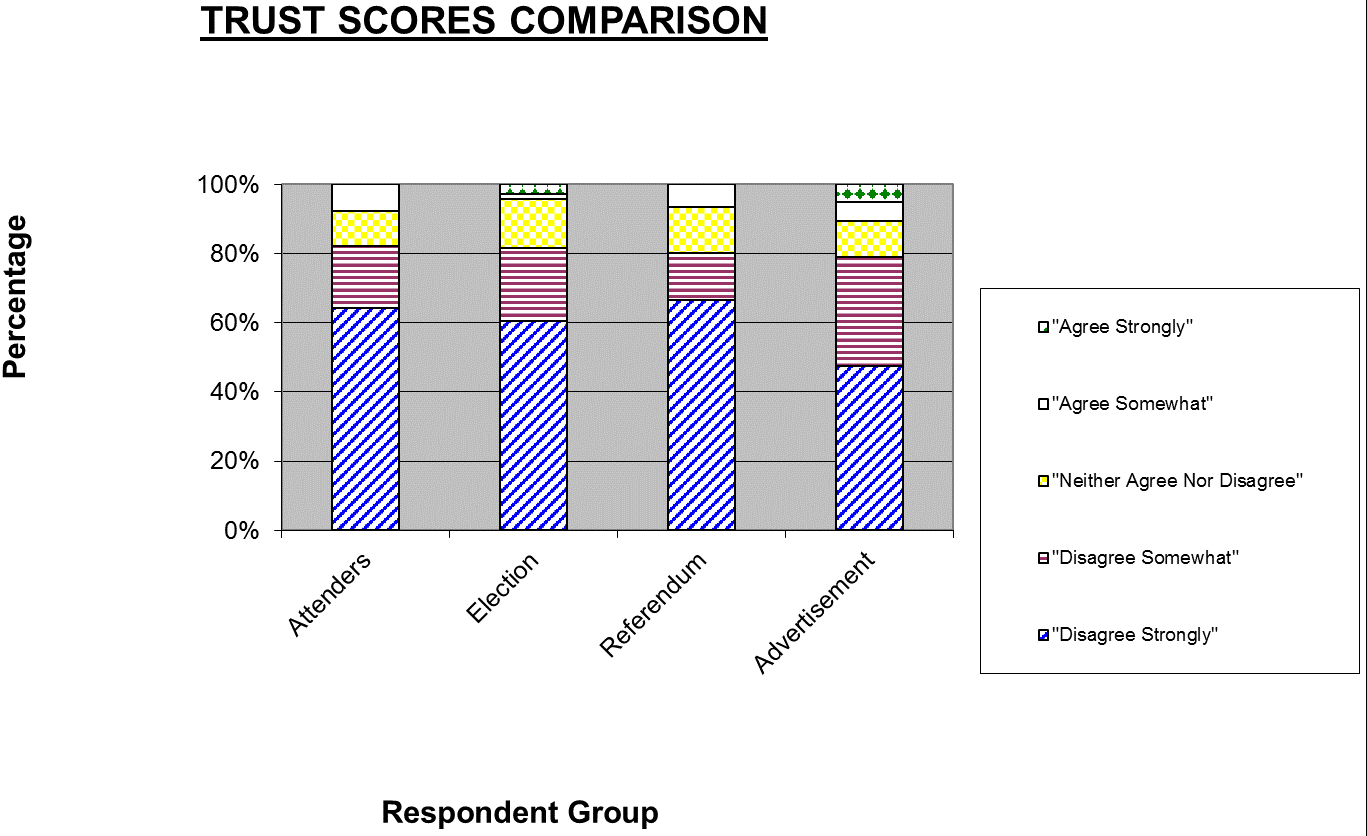

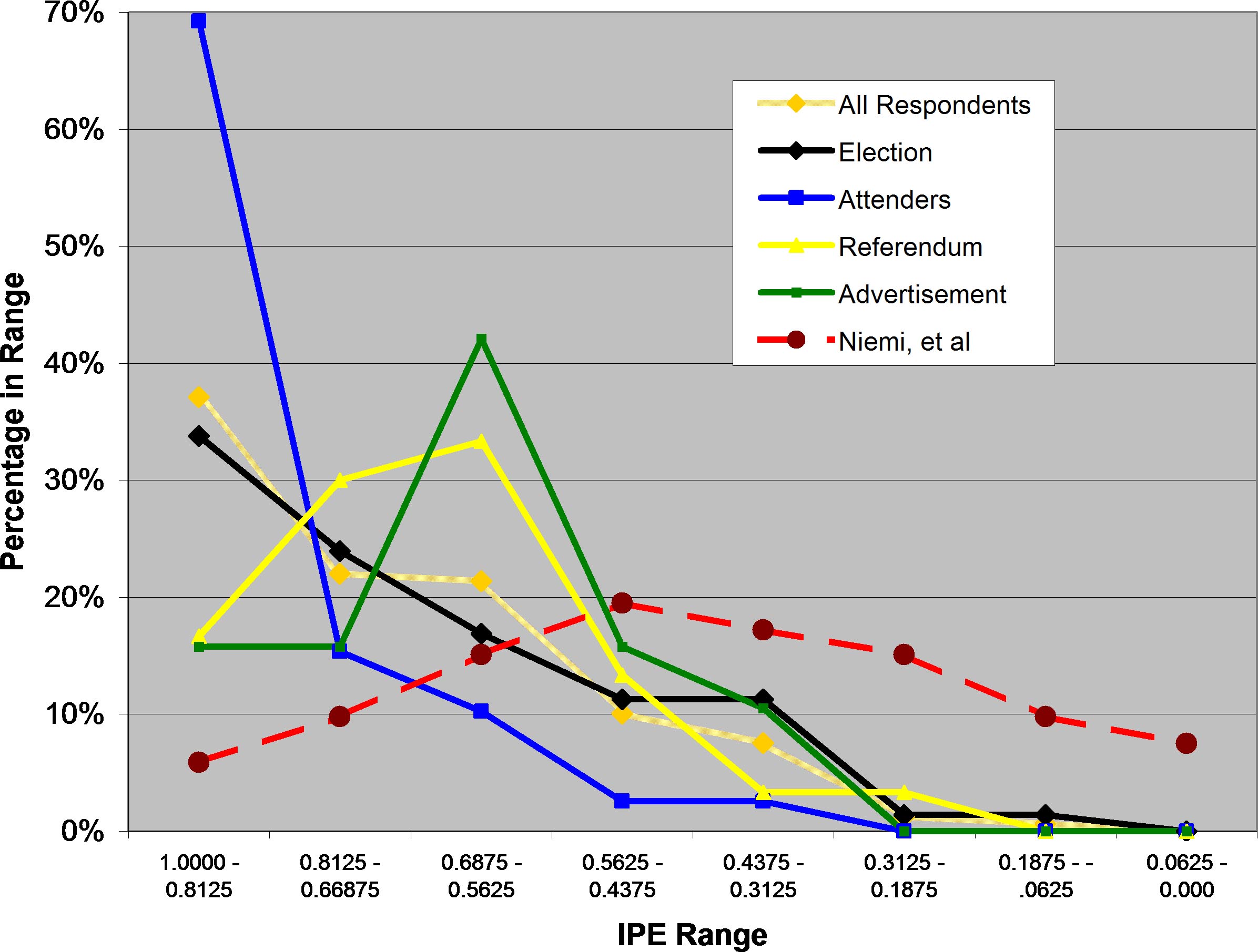

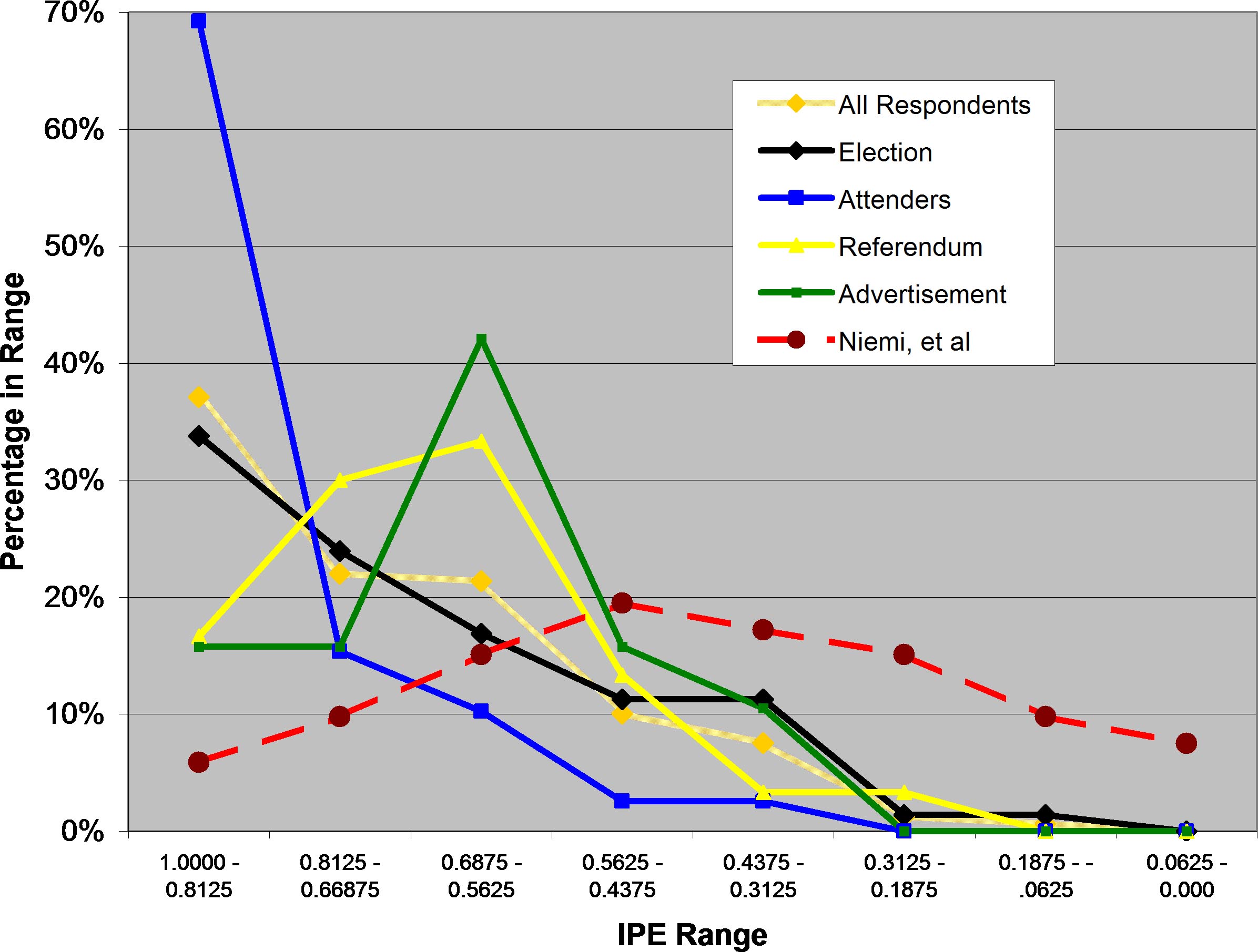

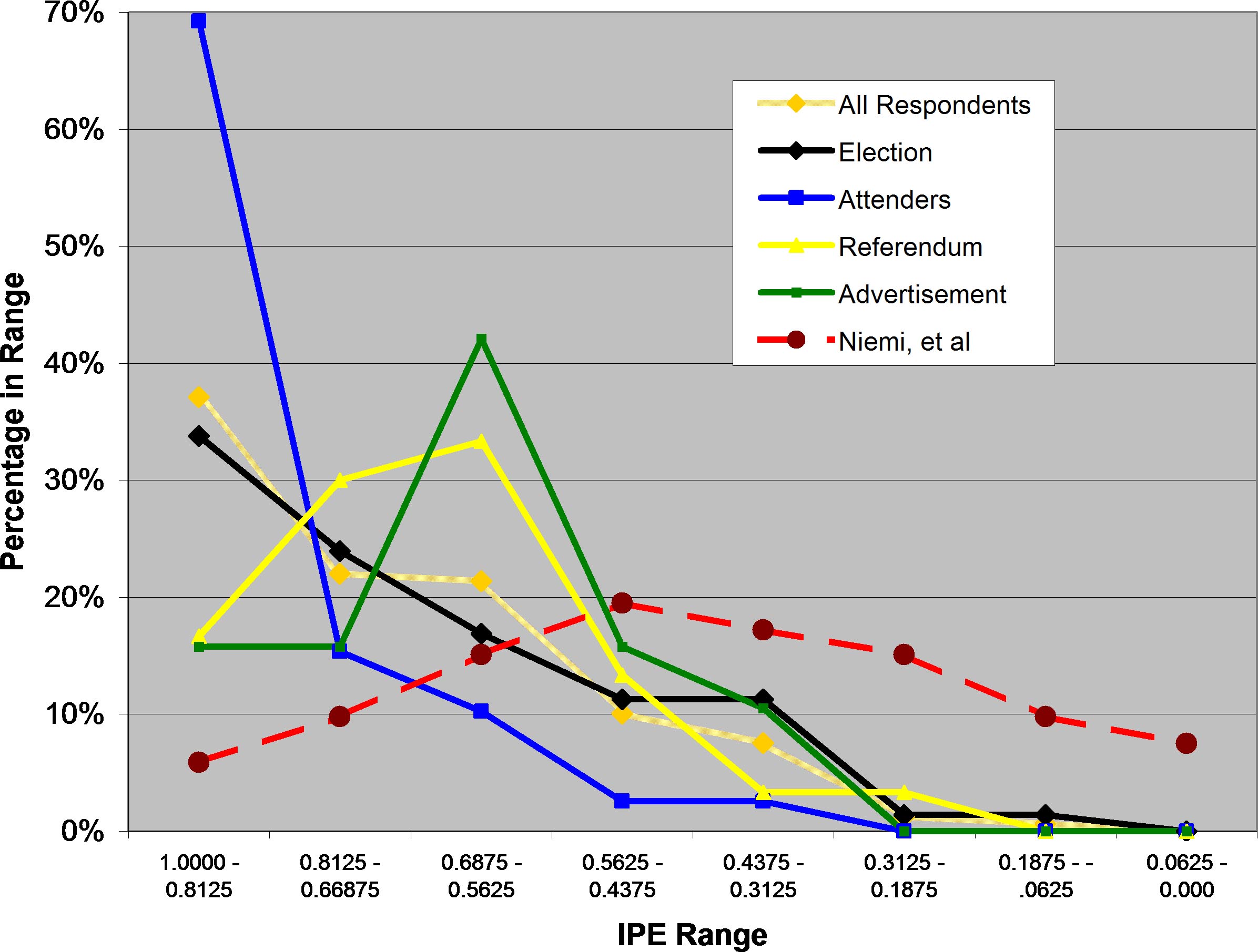

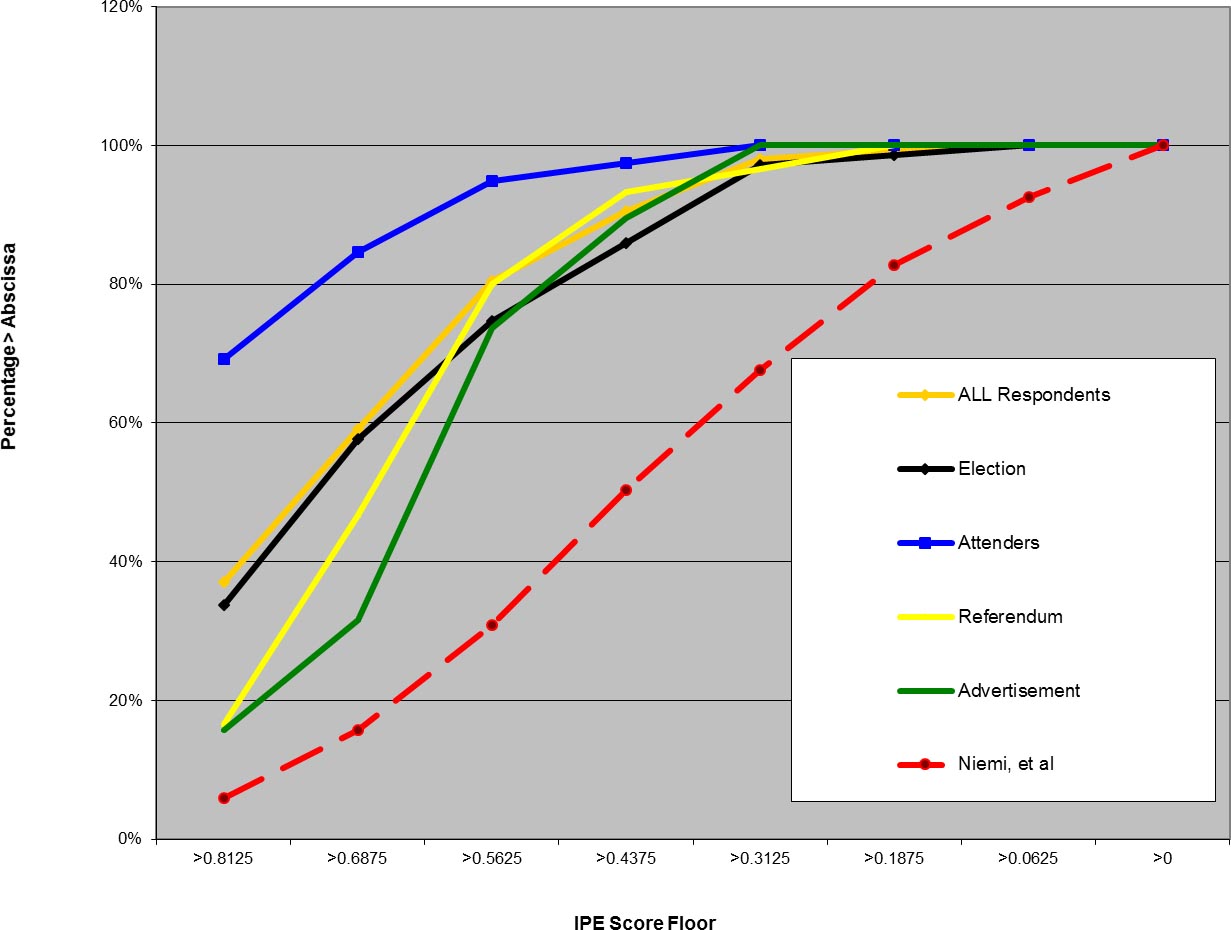

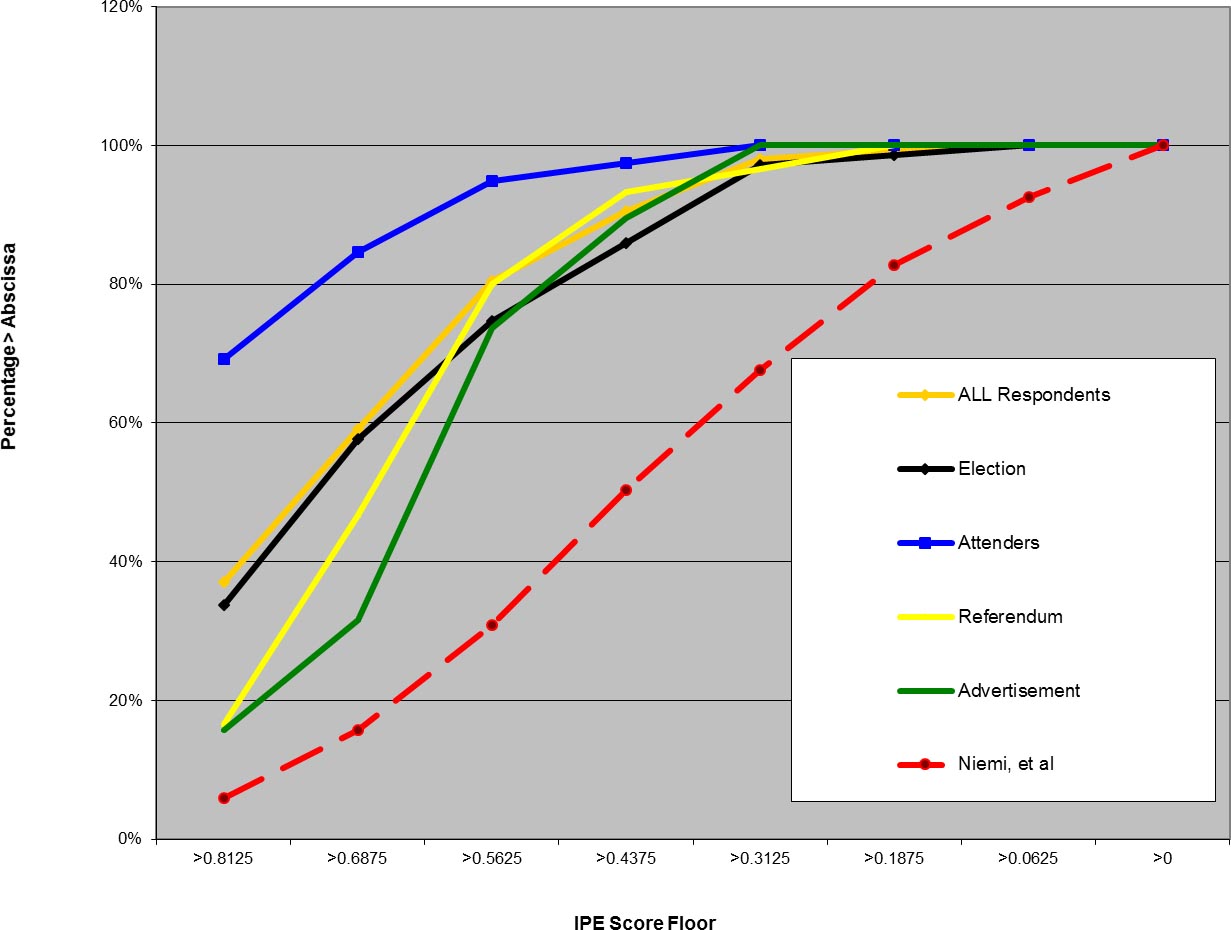

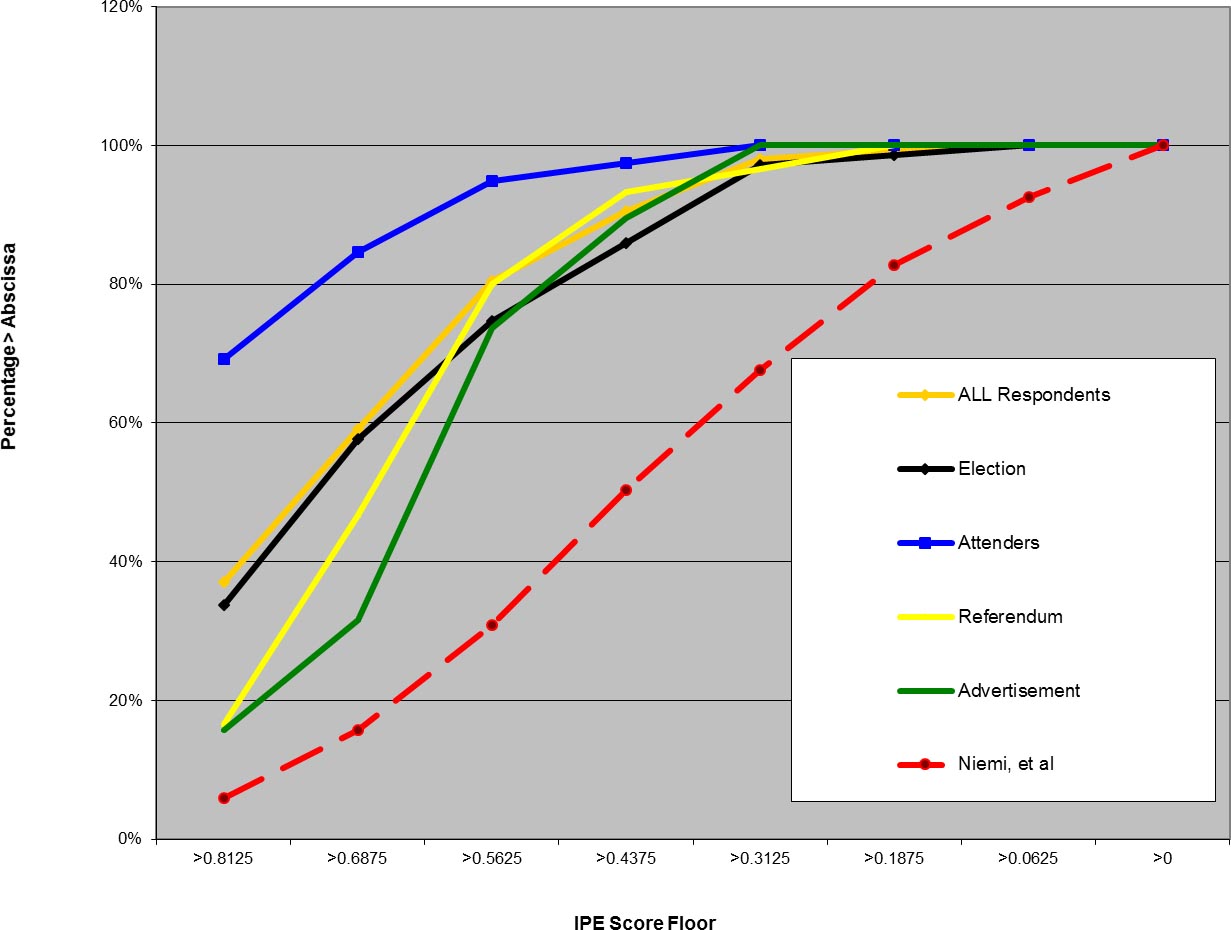

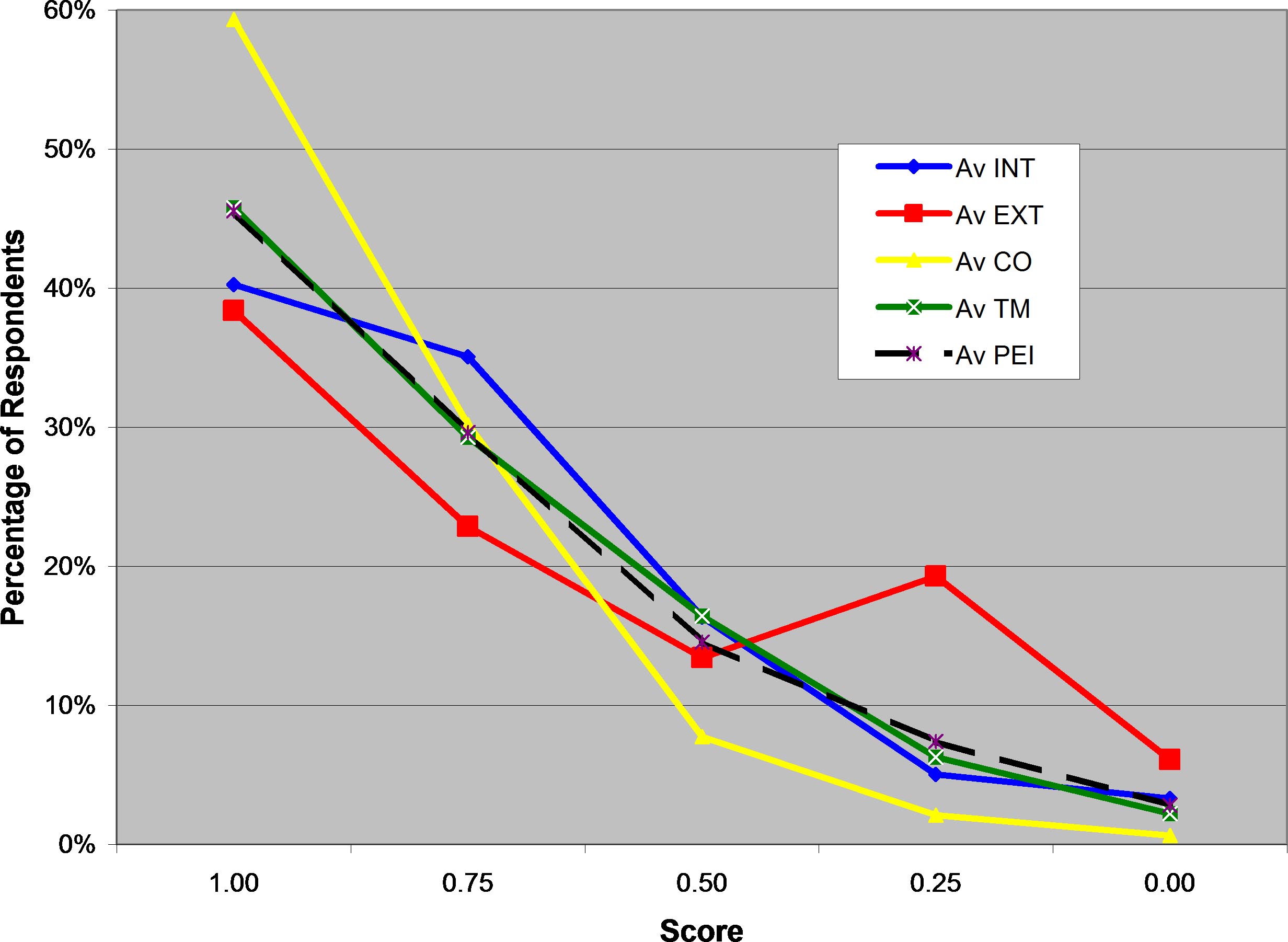

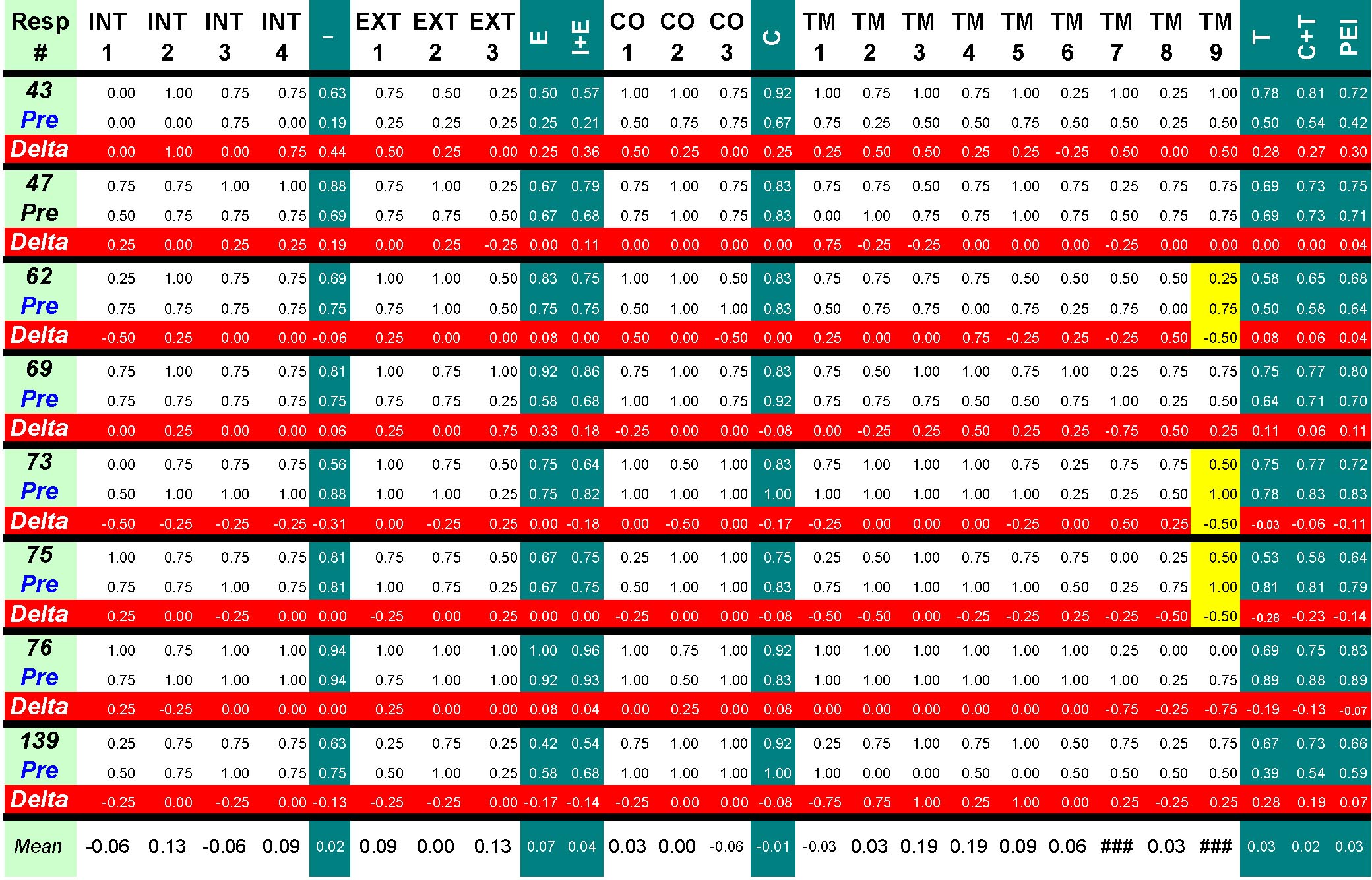

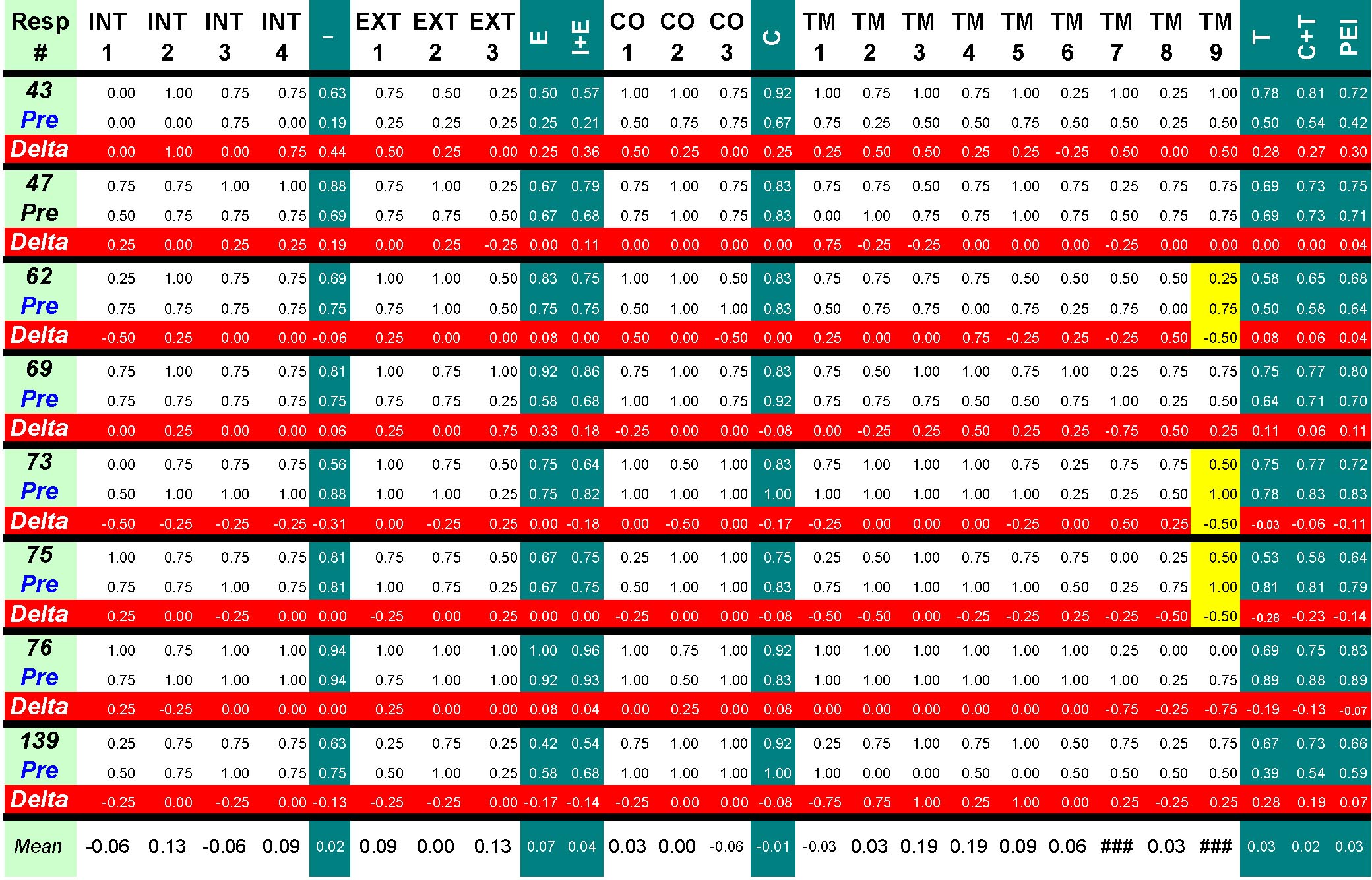

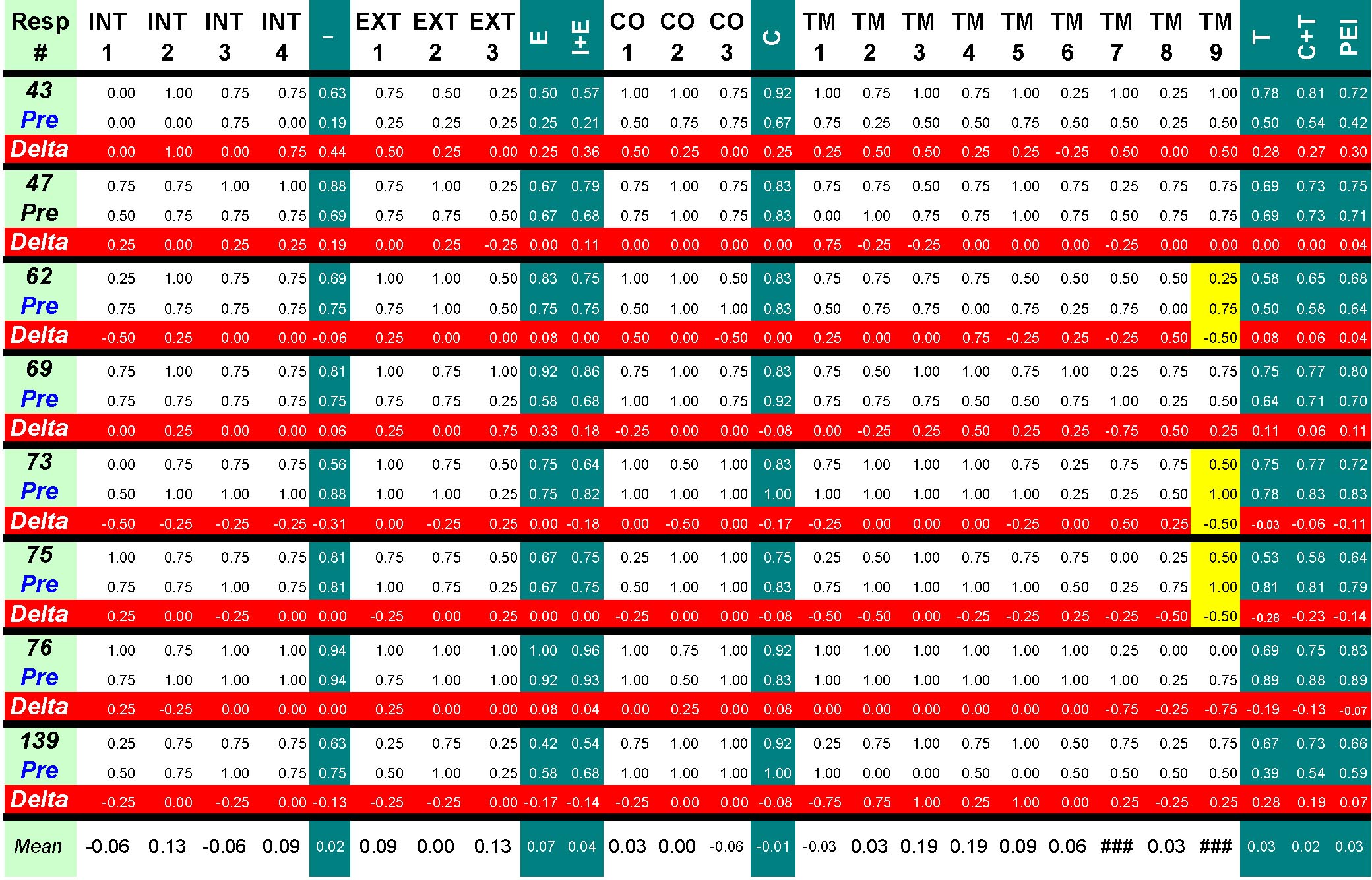

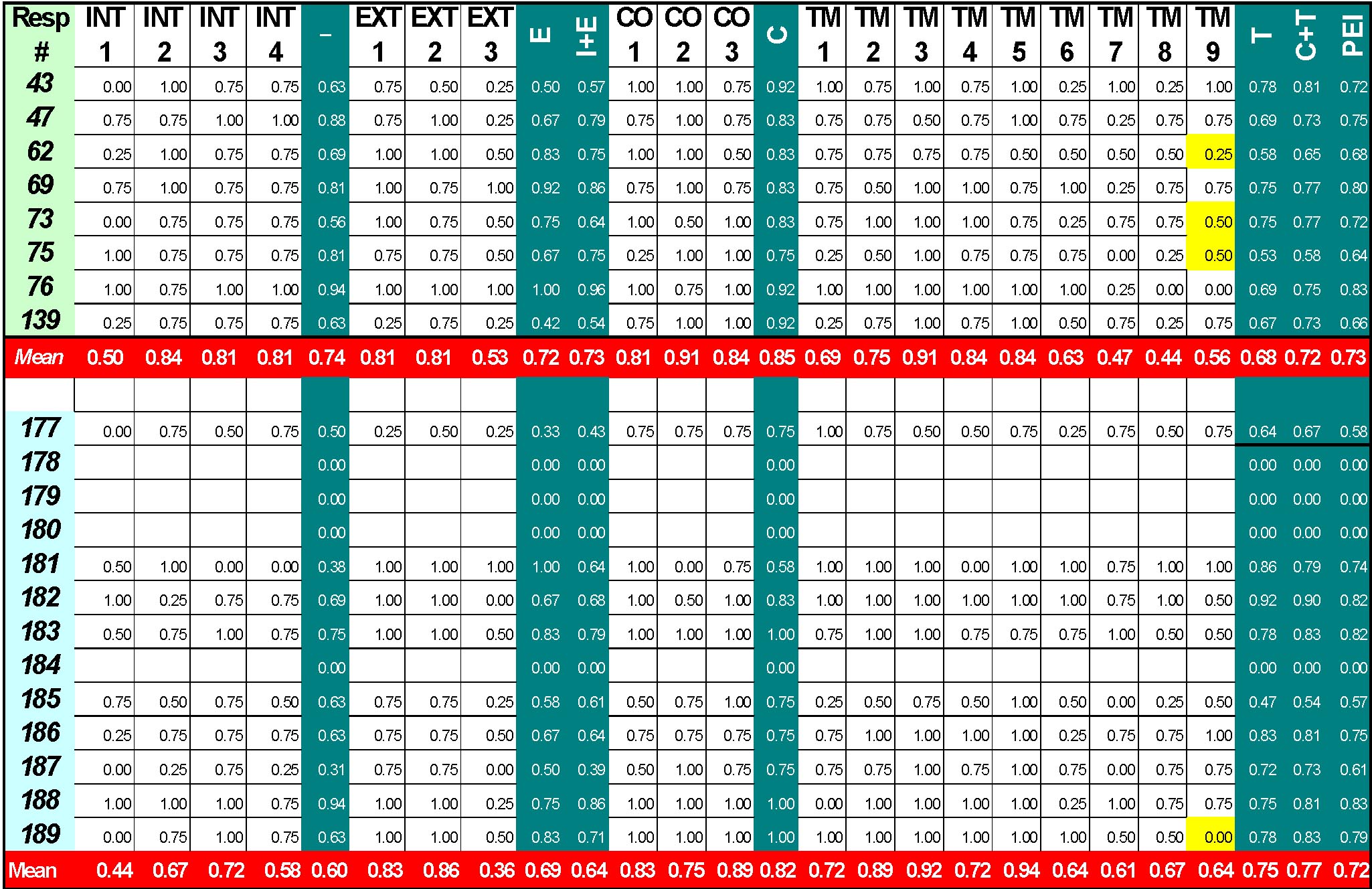

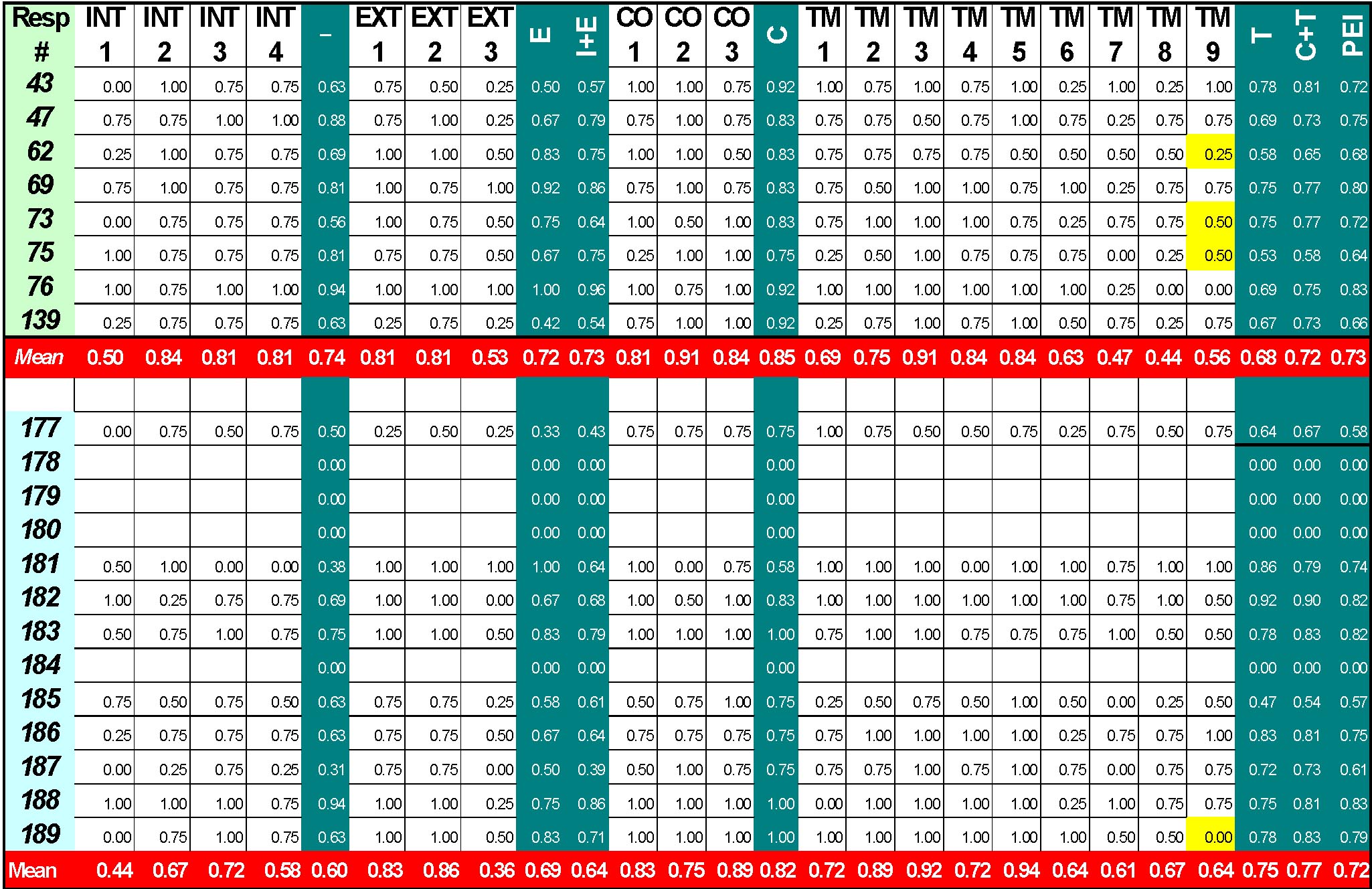

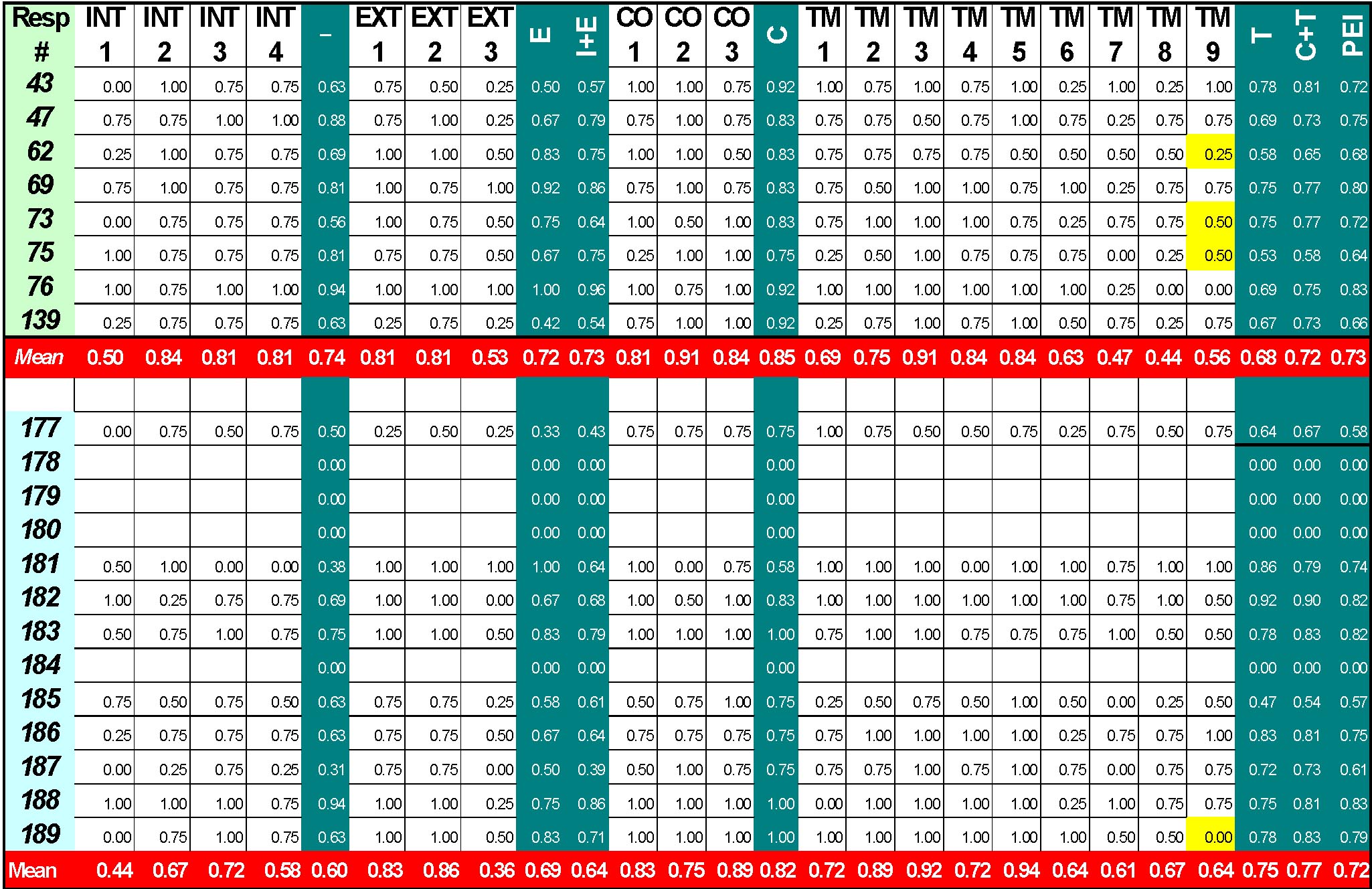

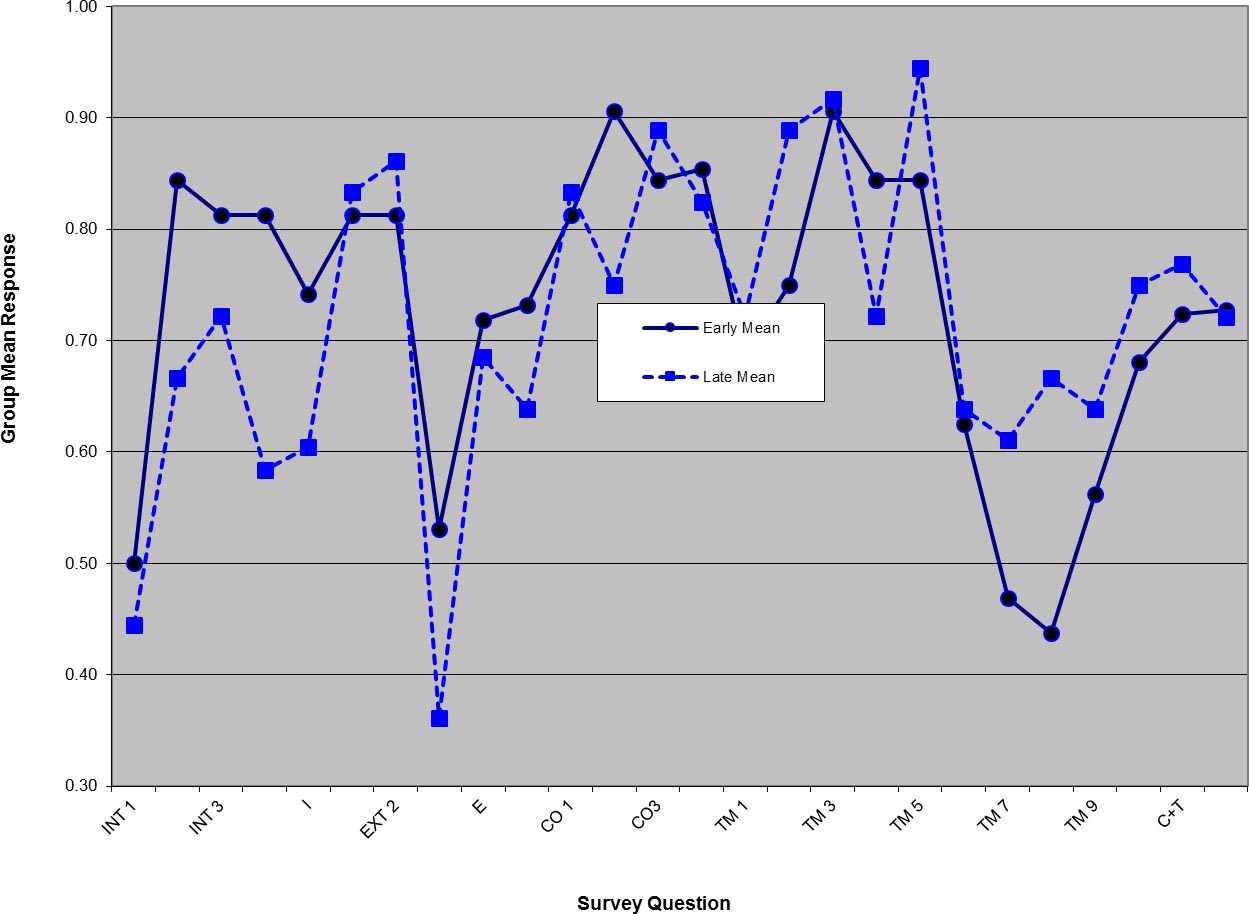

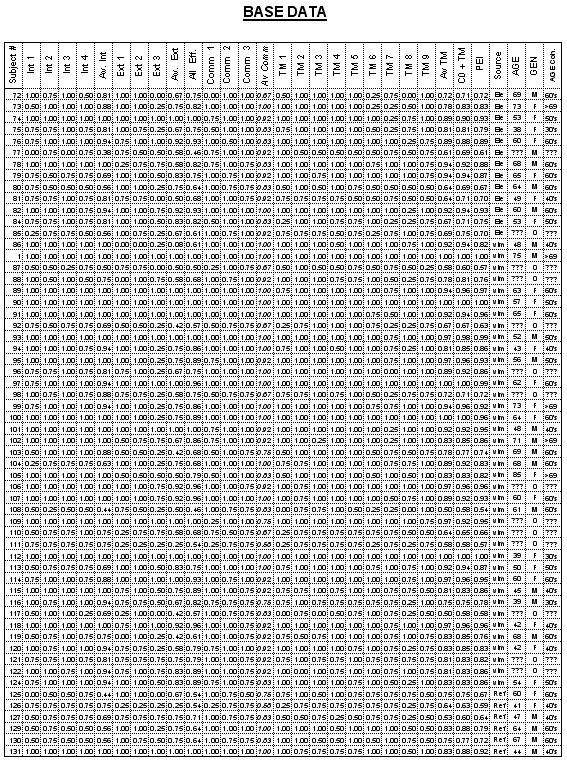

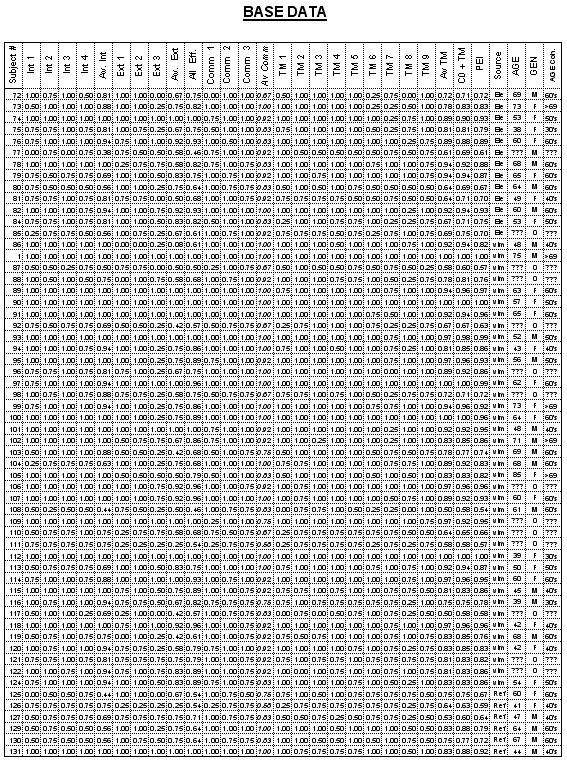

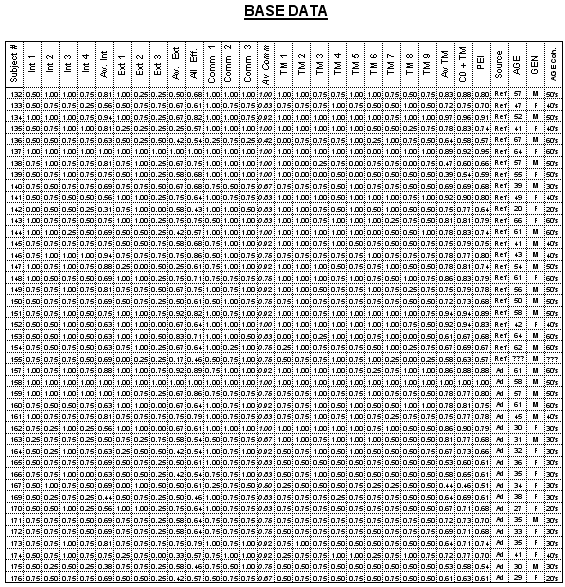

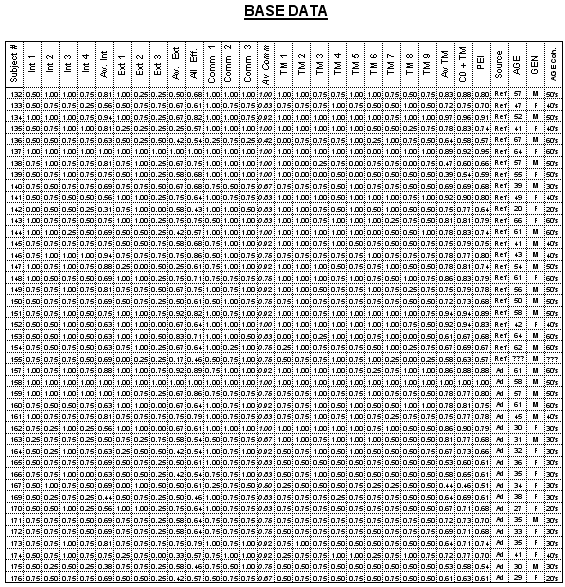

A second objective of the virtual town meeting study was to ascertain whether or not there was a measurable relationship between town meeting participation and individual feelings of political efficacy. The mechanism employed to address this question was a survey questionnaire. The opportunity to respond to the questionnaire was offered on several occasions. Not all respondents to the questionnaire signed up to participate remotely. Many, but not all, eligible remote participants filled out a questionnaire. Some respondents provided no identification thereby eliminating the possibility of following up with a post participation survey (which would complete the inputs required for a true PrePost survey). The result of the survey questionnaire is a set of data that provides insights into the relationship between participation and feelings of political efficacy, that correlates well with the data of Niemi et al, but that provides only sparse PrePost data that might establish the direction of the causal arrow between participation and political efficacy.

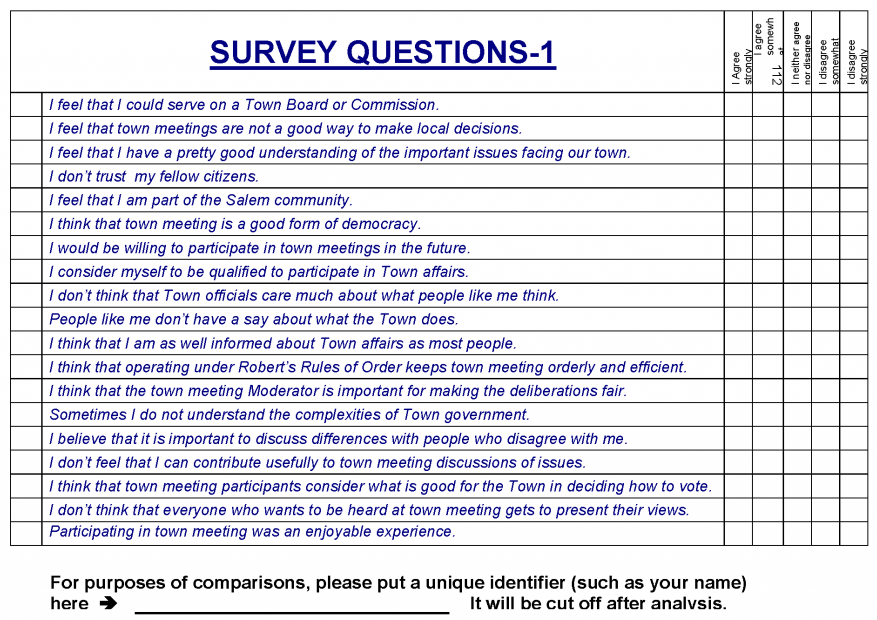

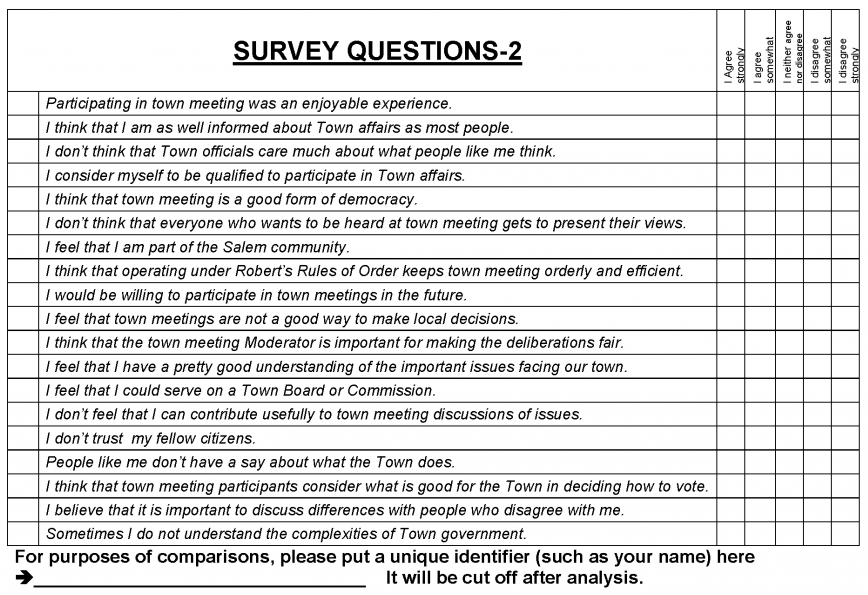

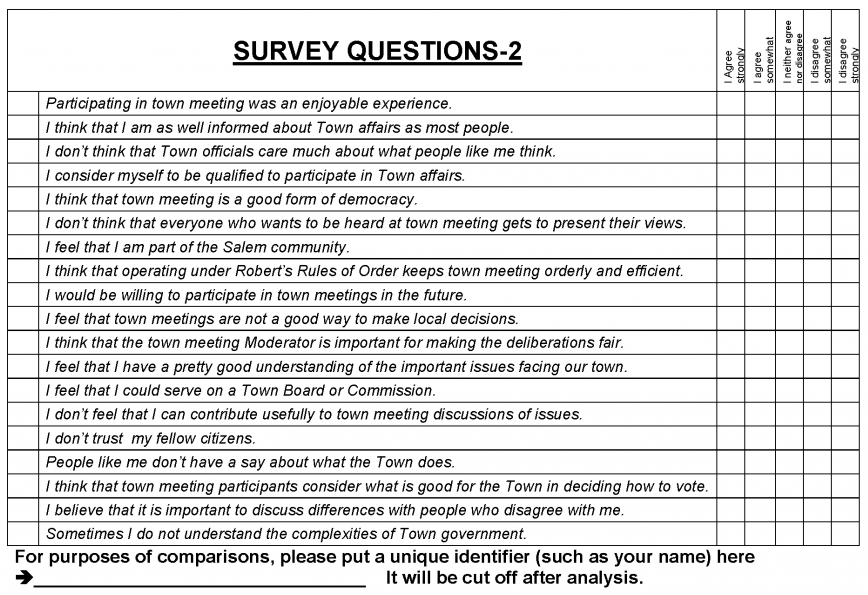

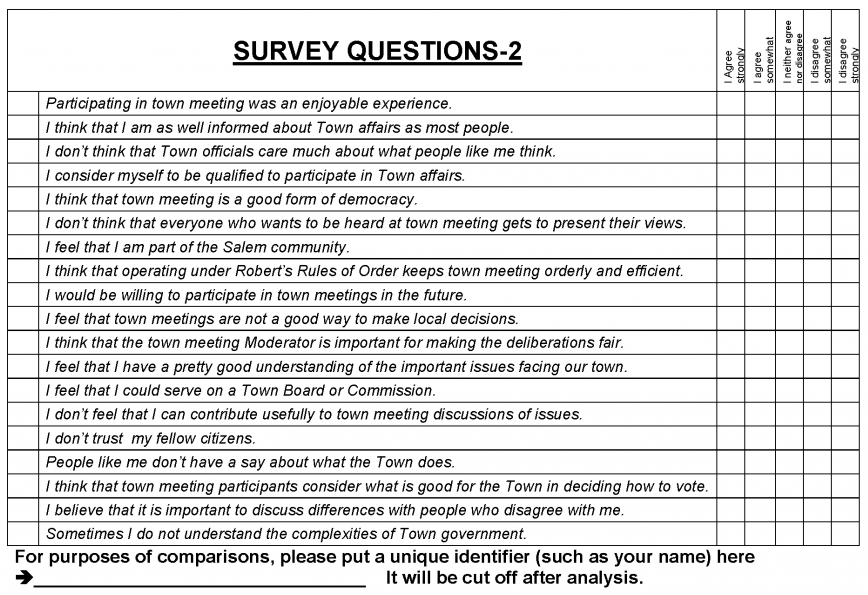

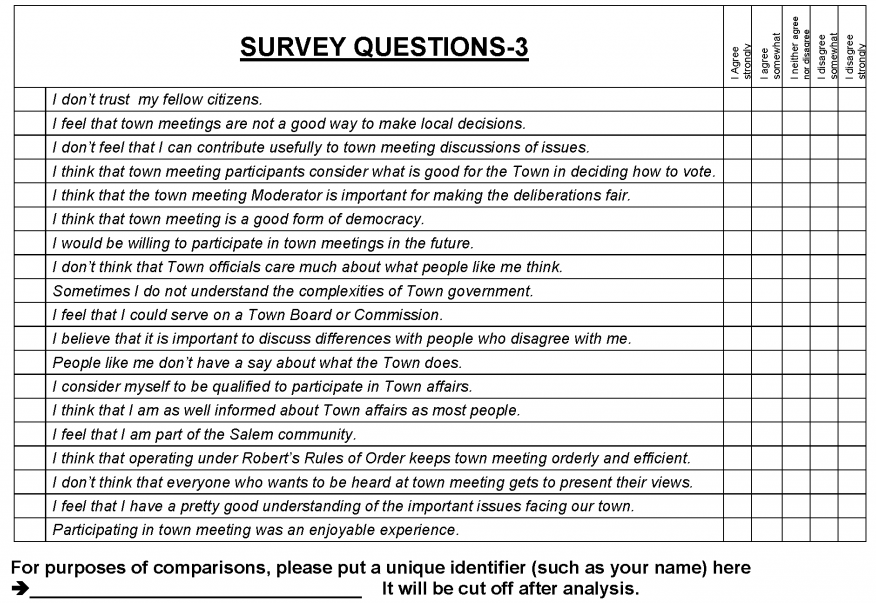

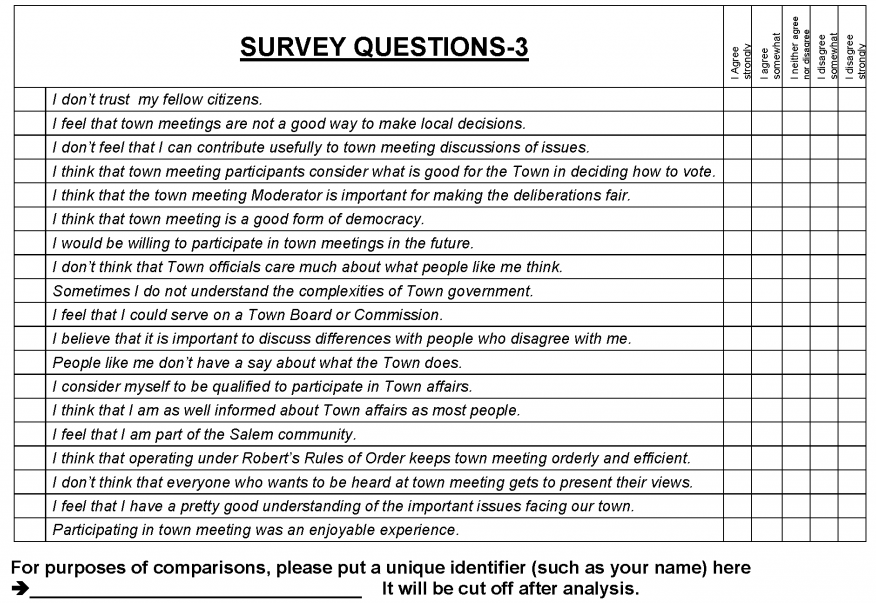

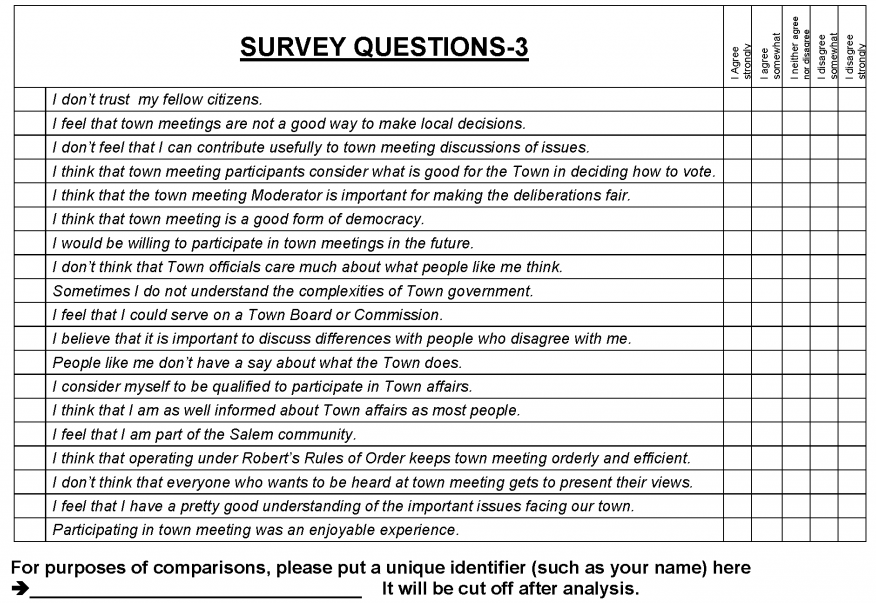

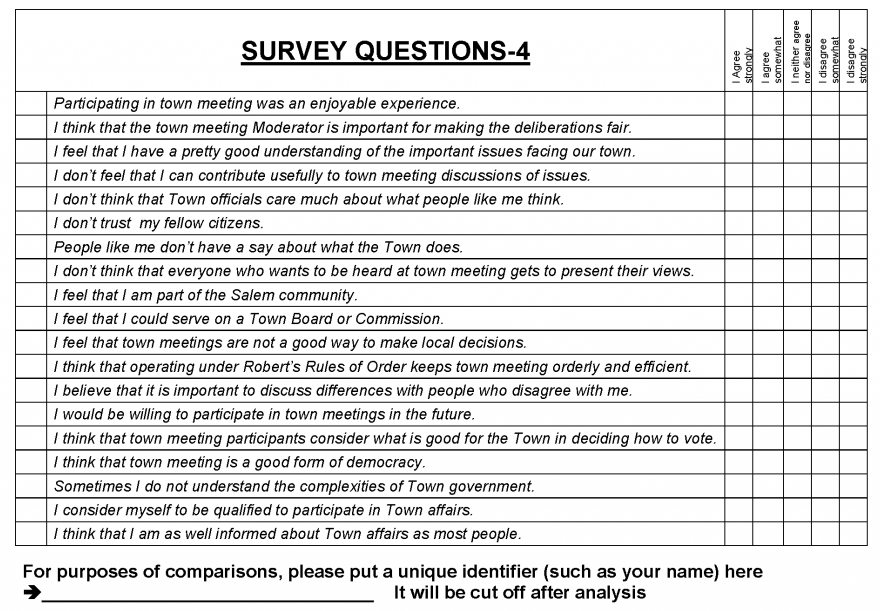

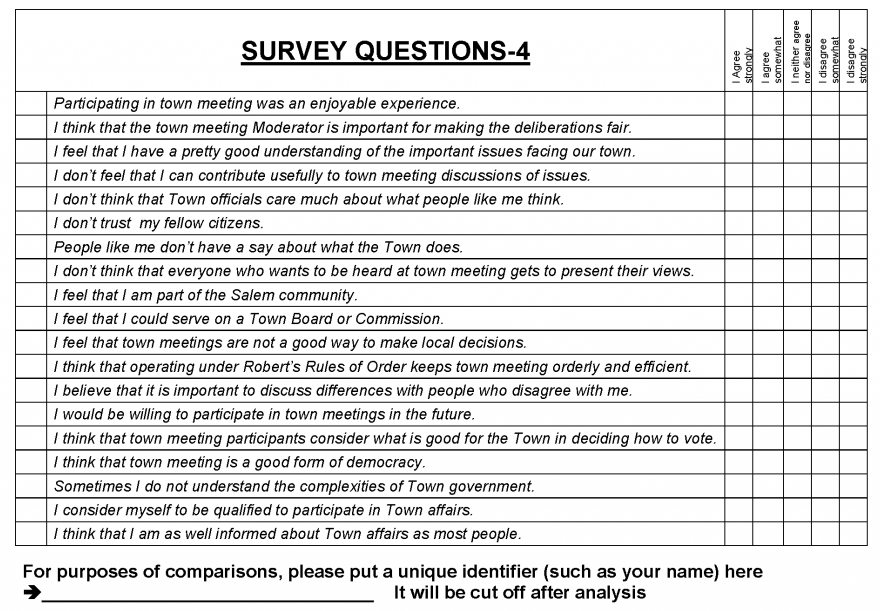

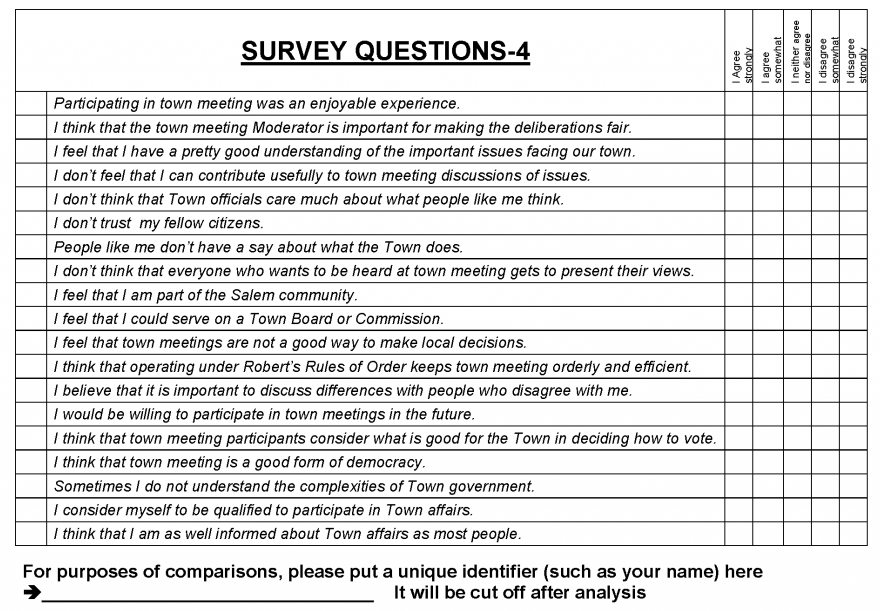

Survey Questionnaire

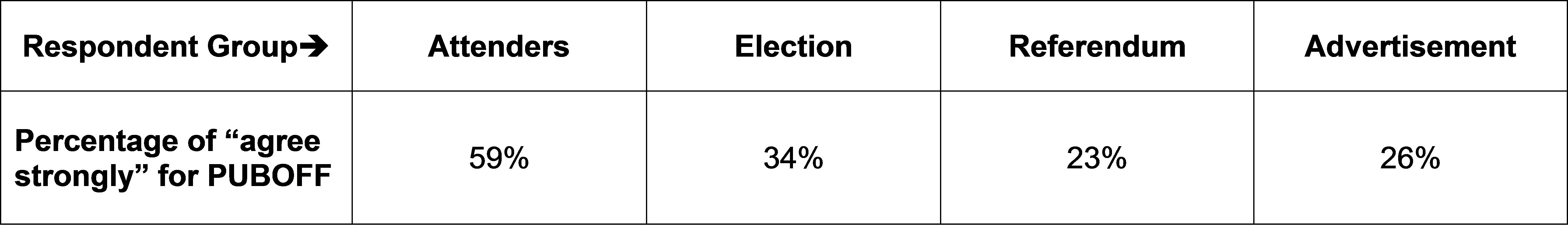

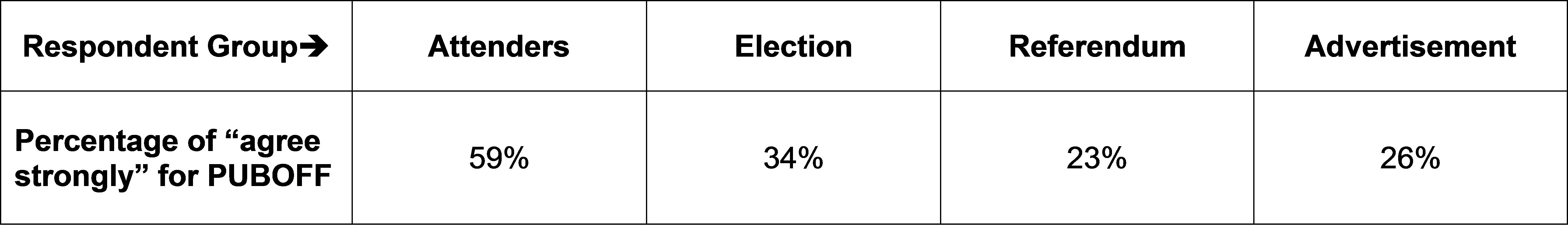

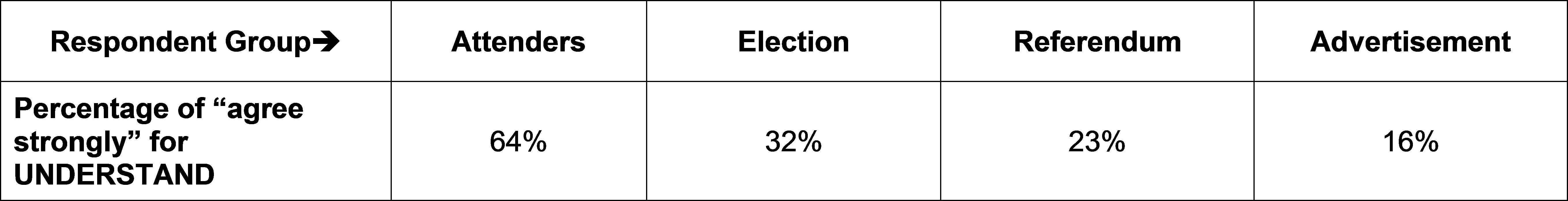

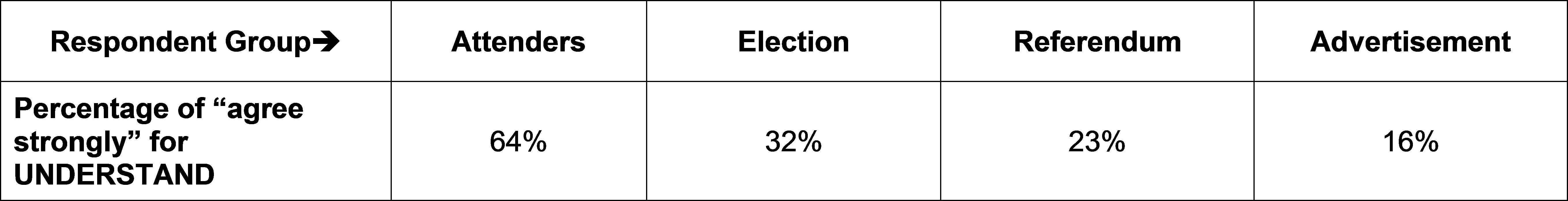

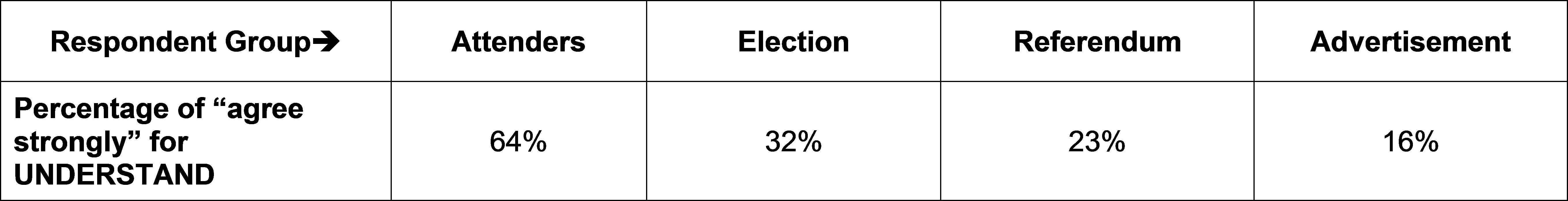

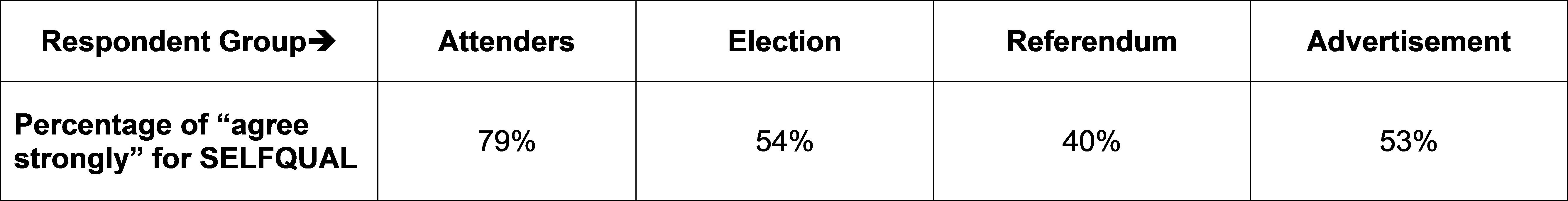

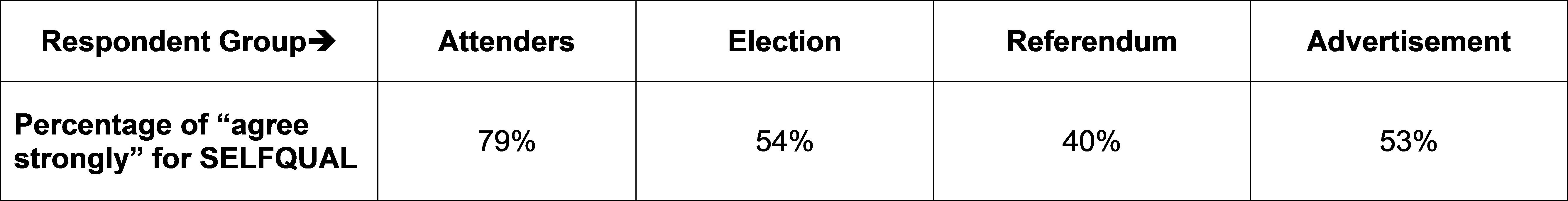

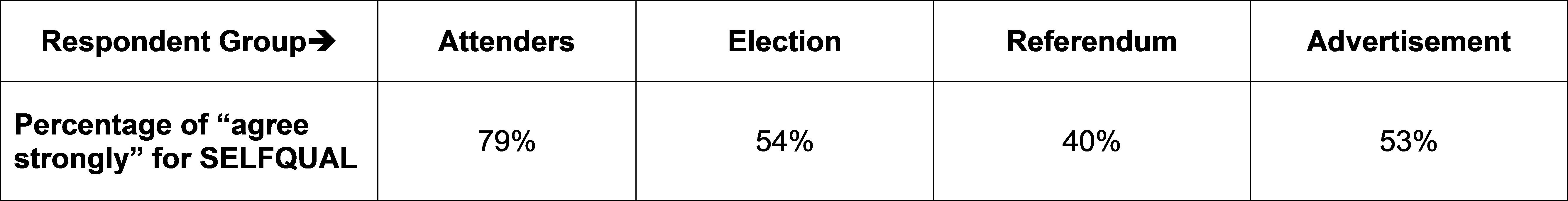

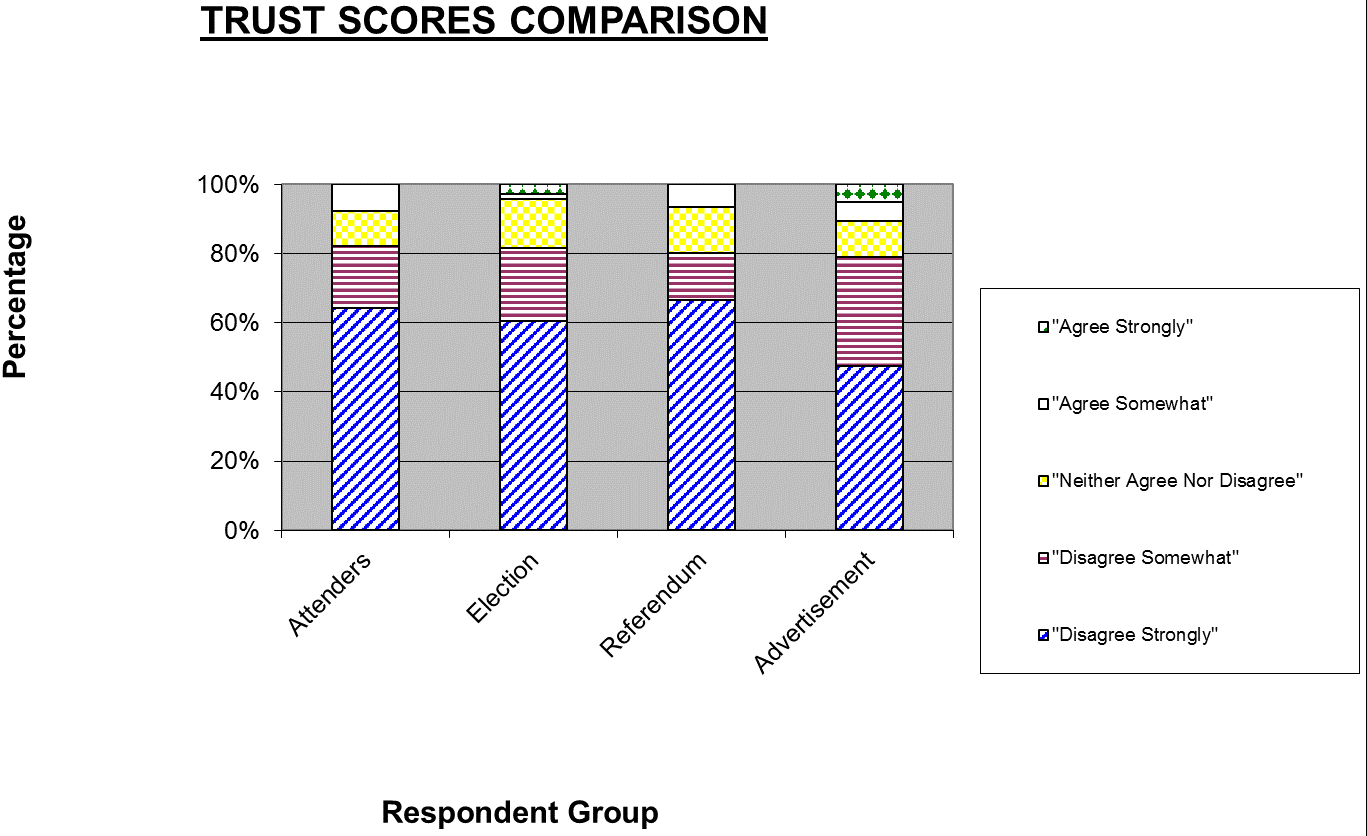

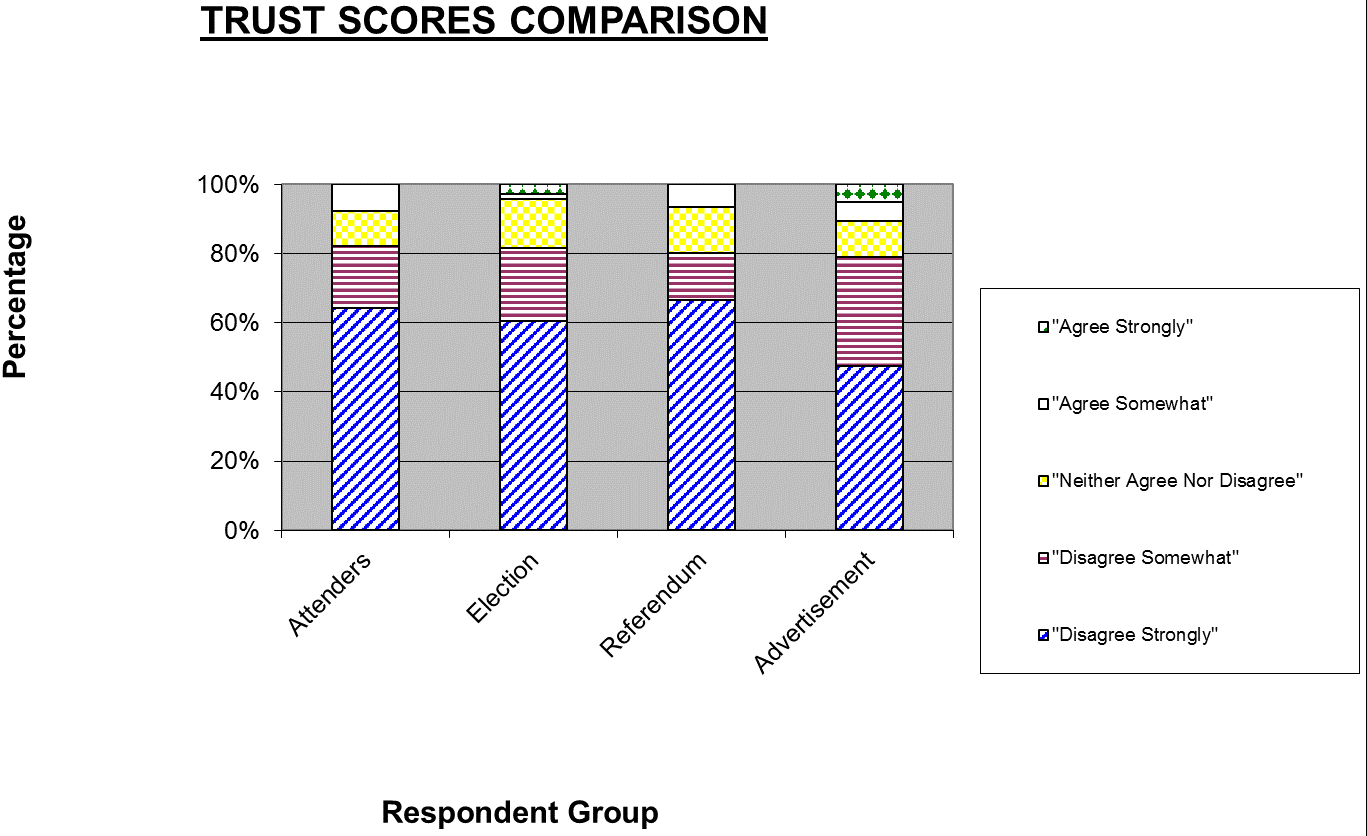

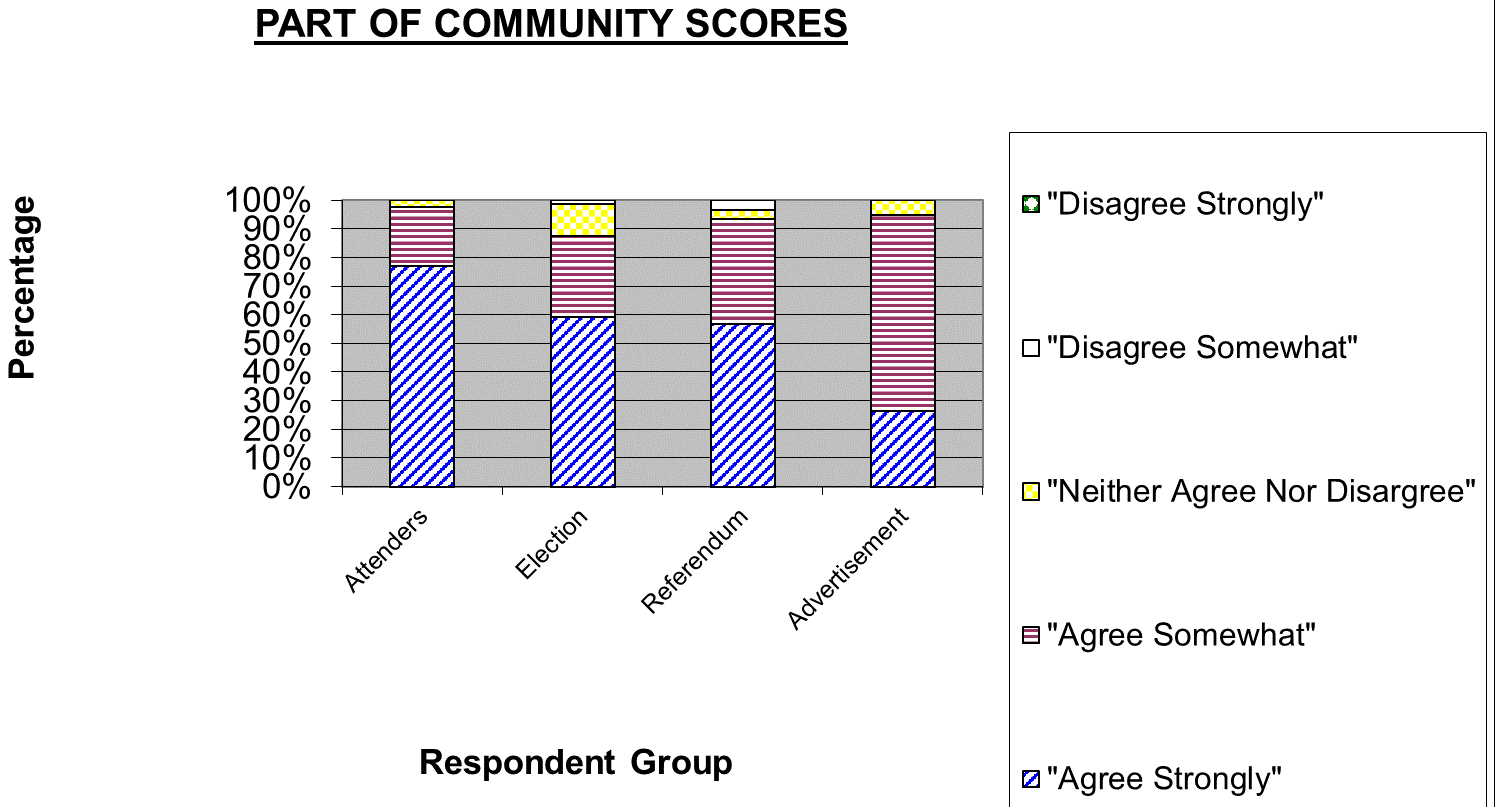

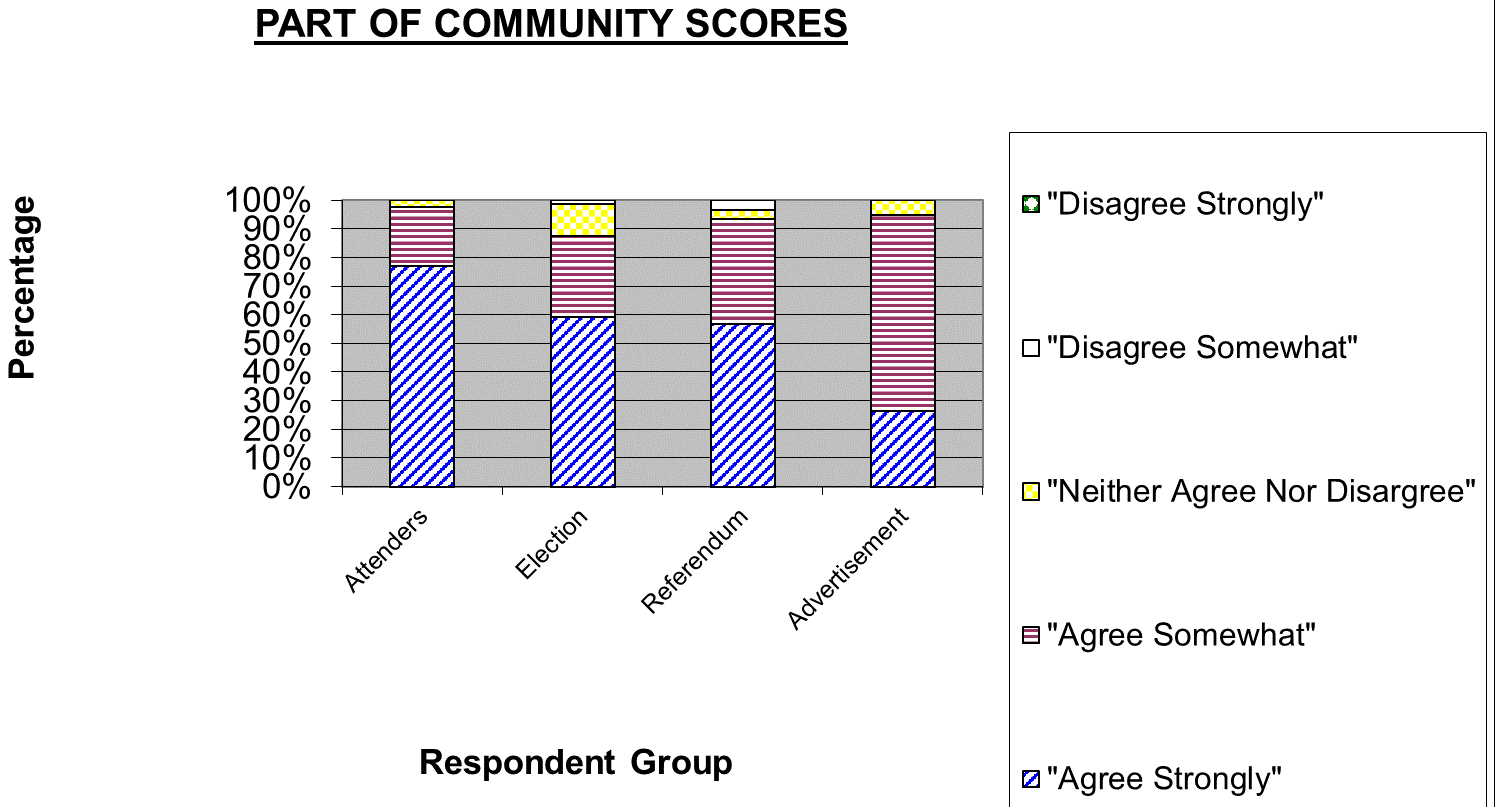

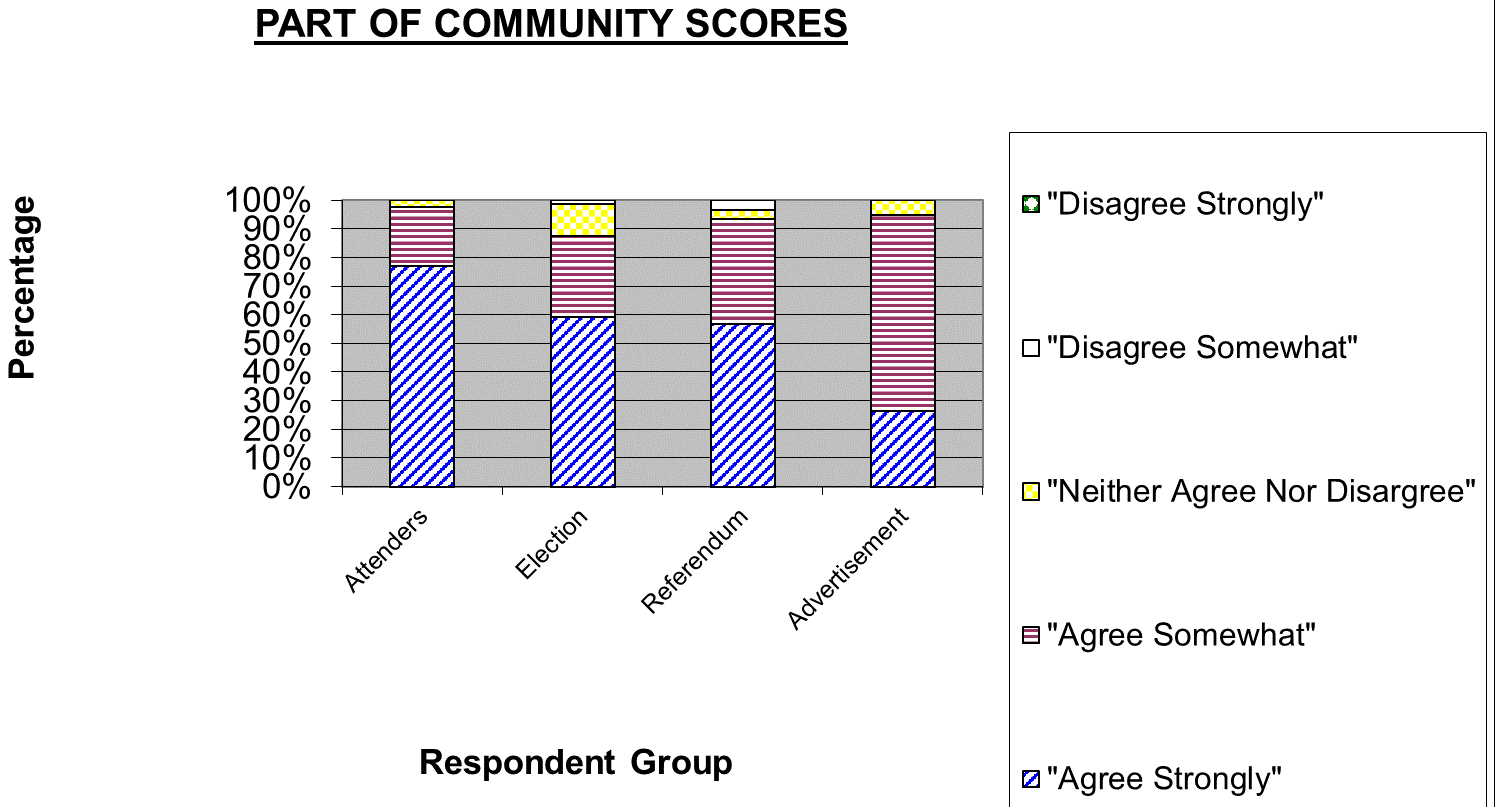

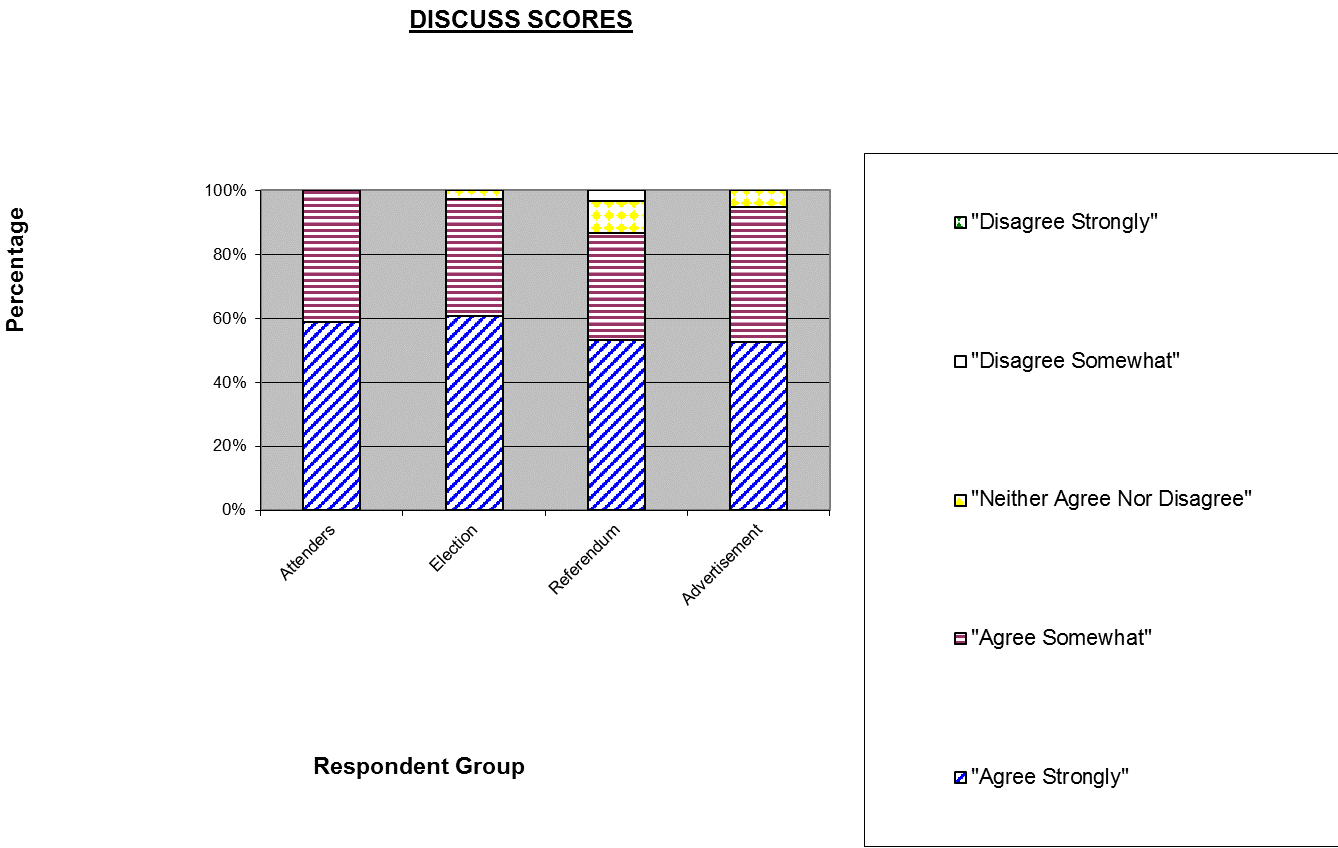

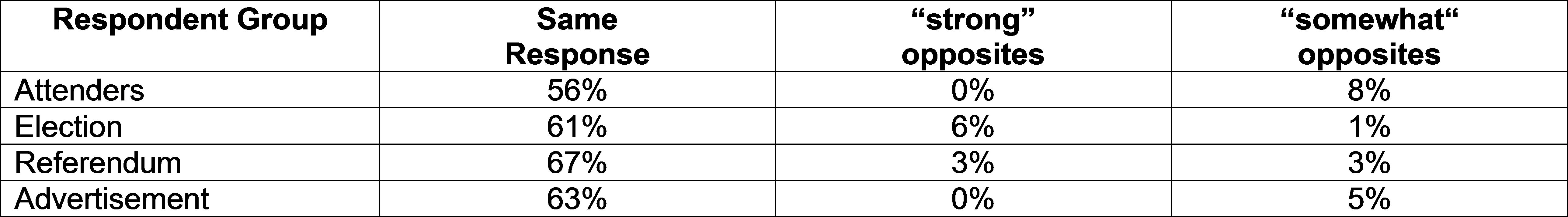

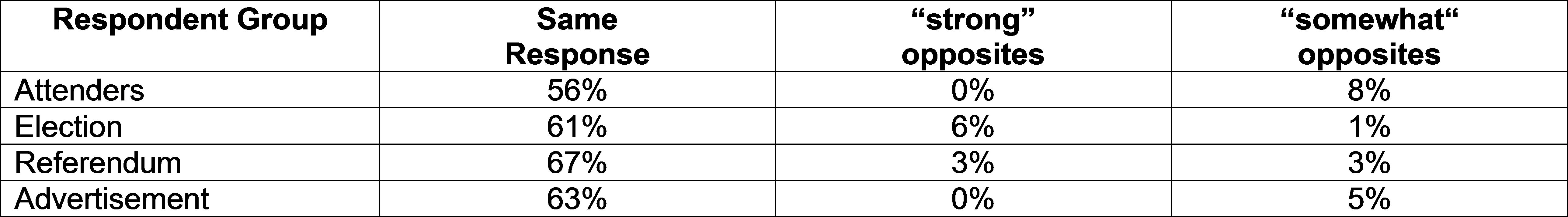

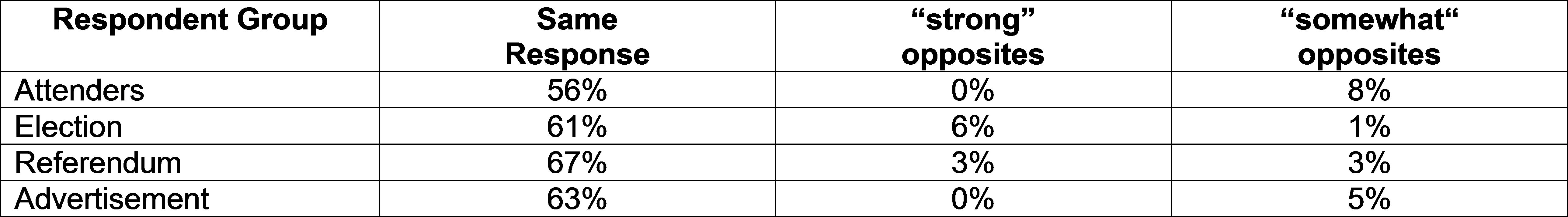

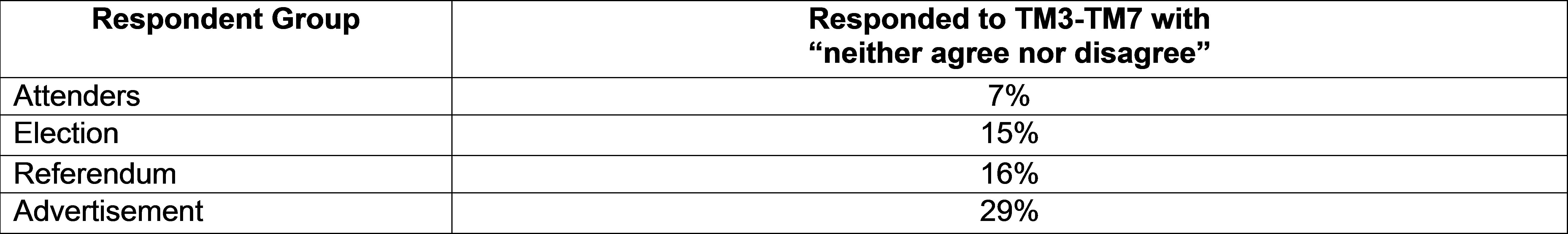

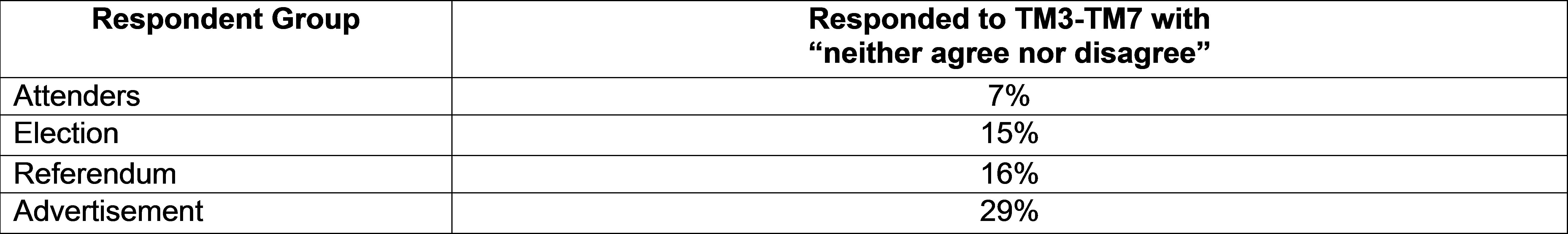

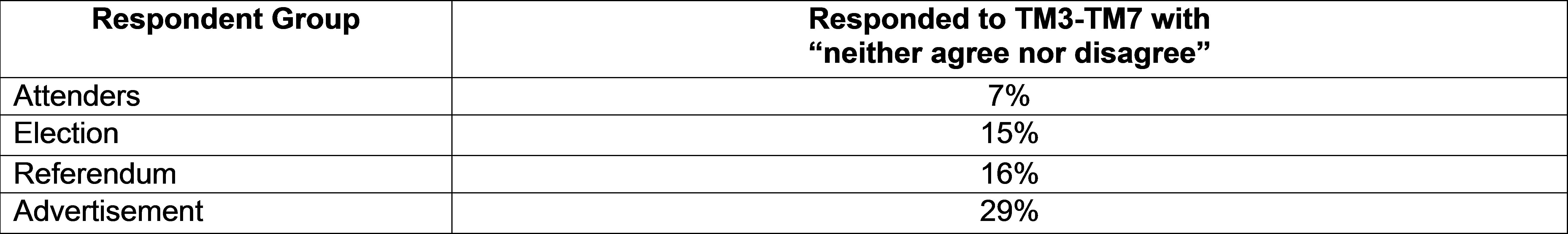

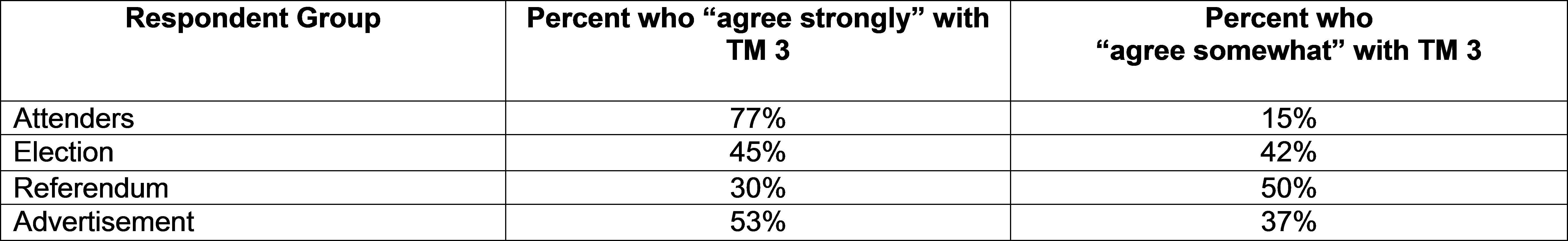

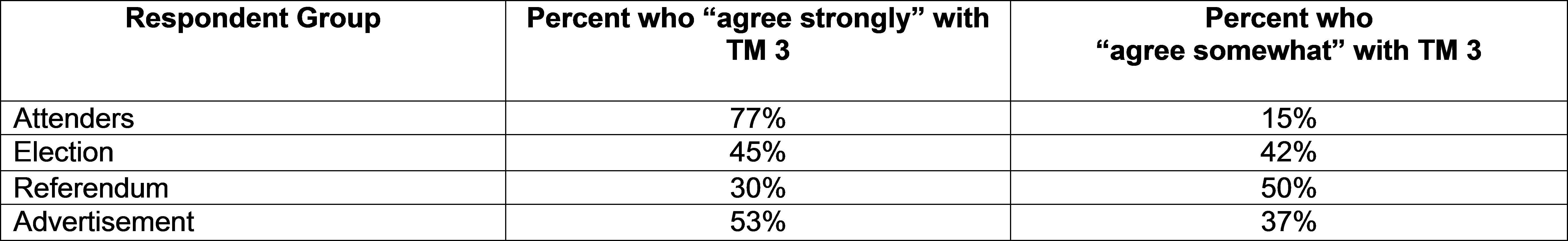

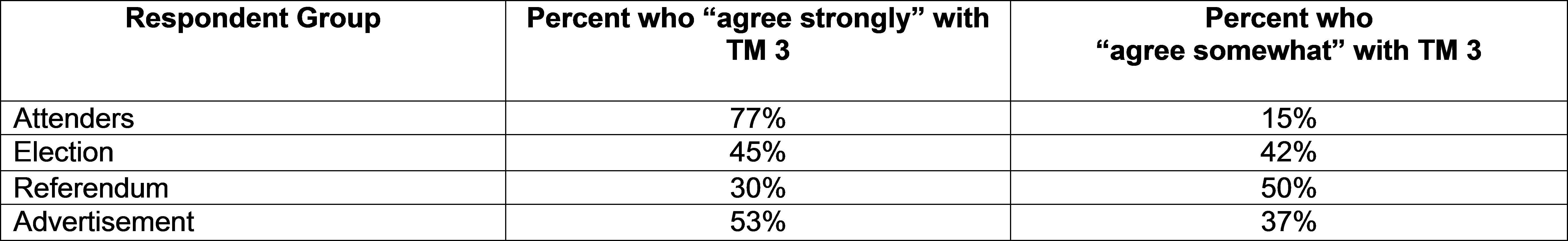

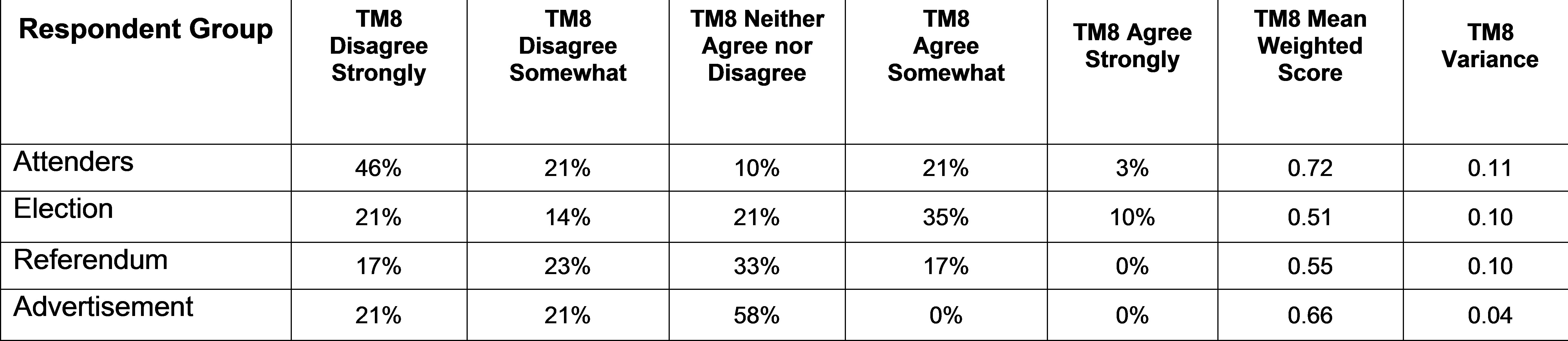

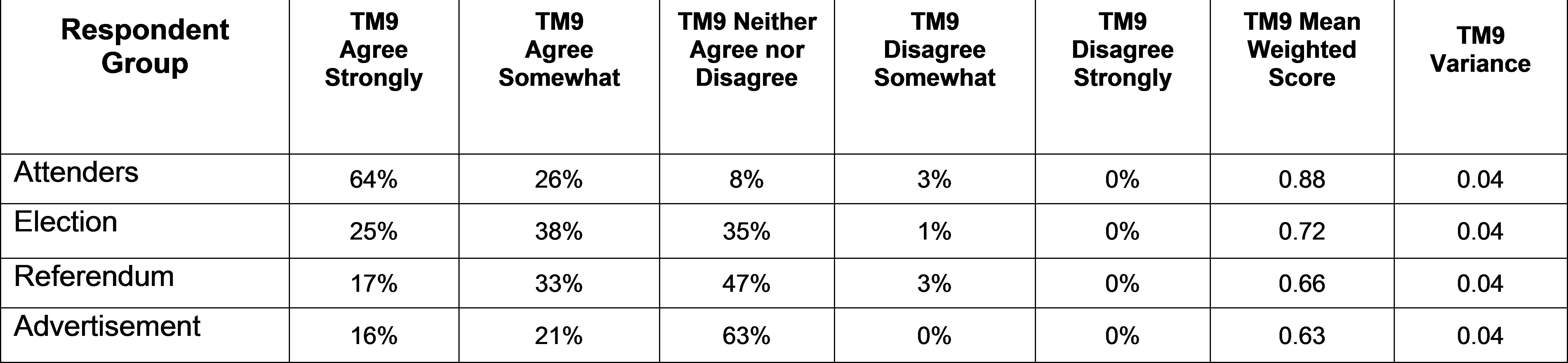

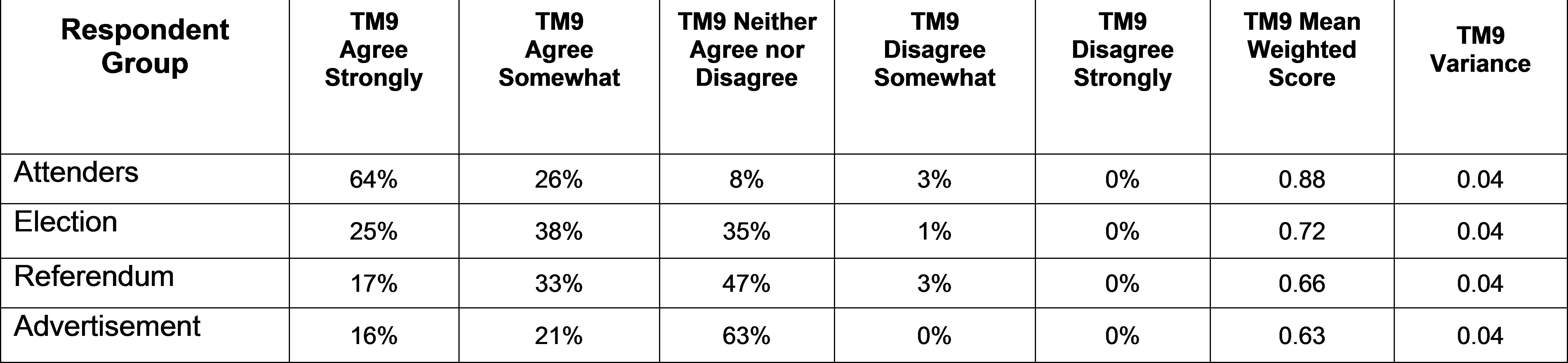

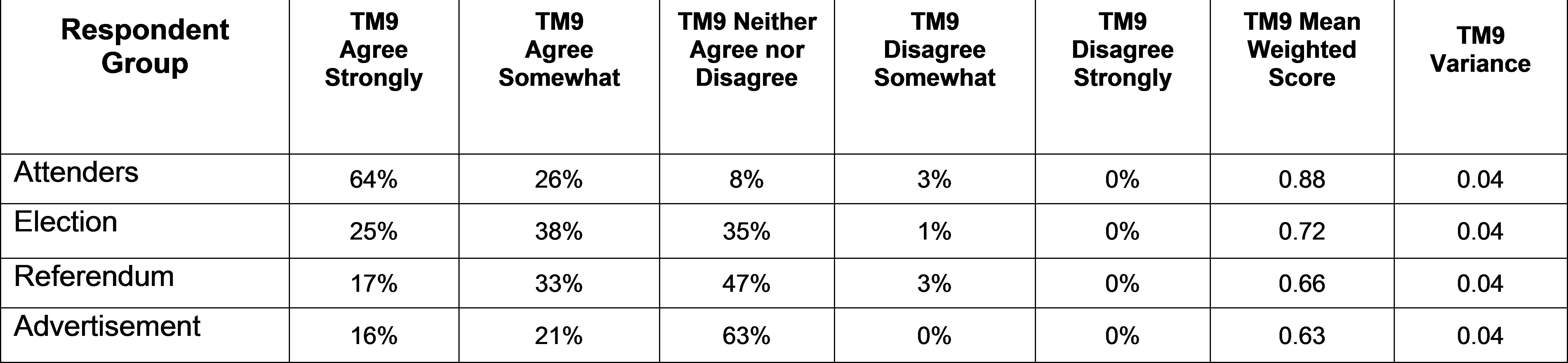

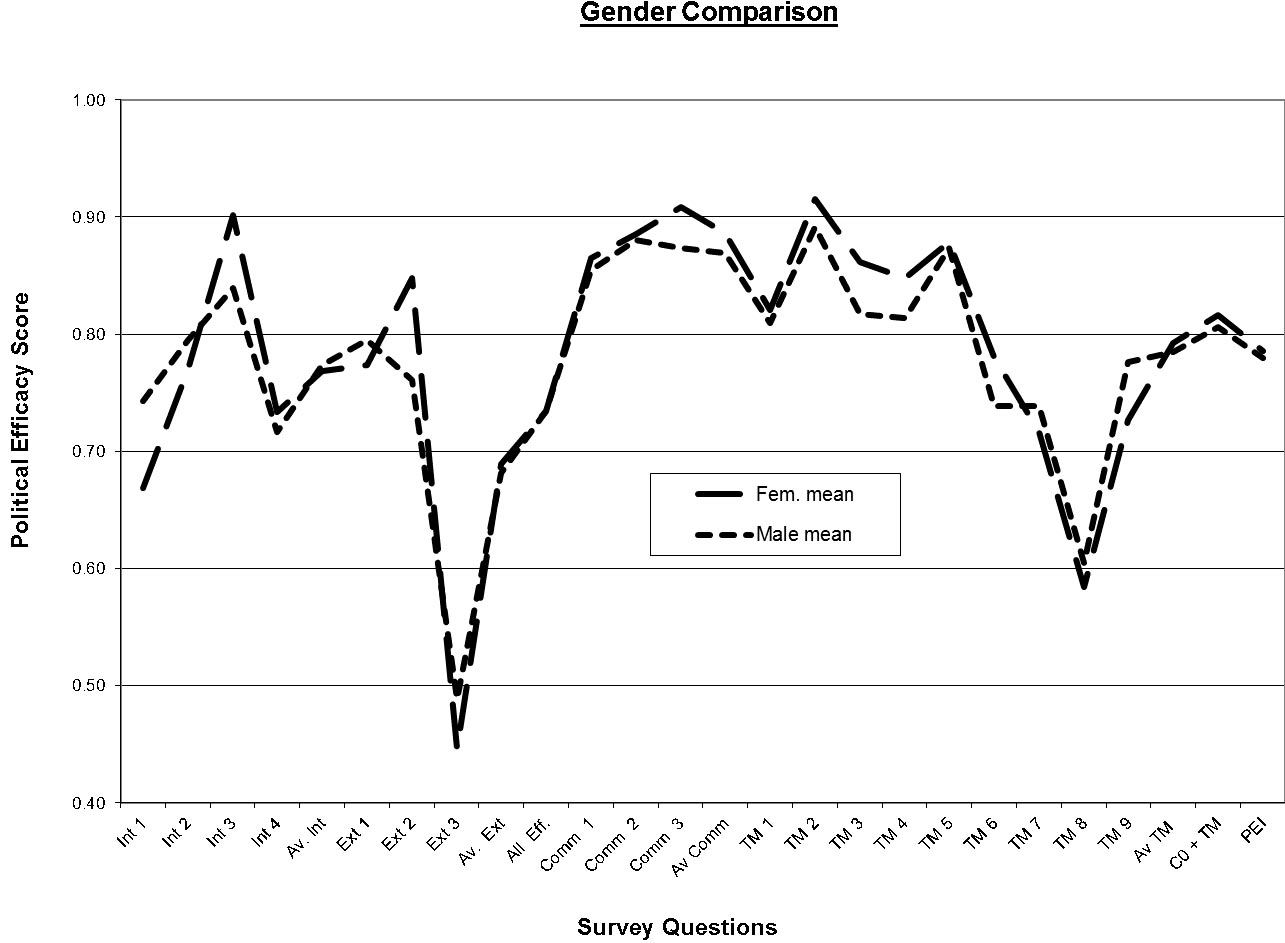

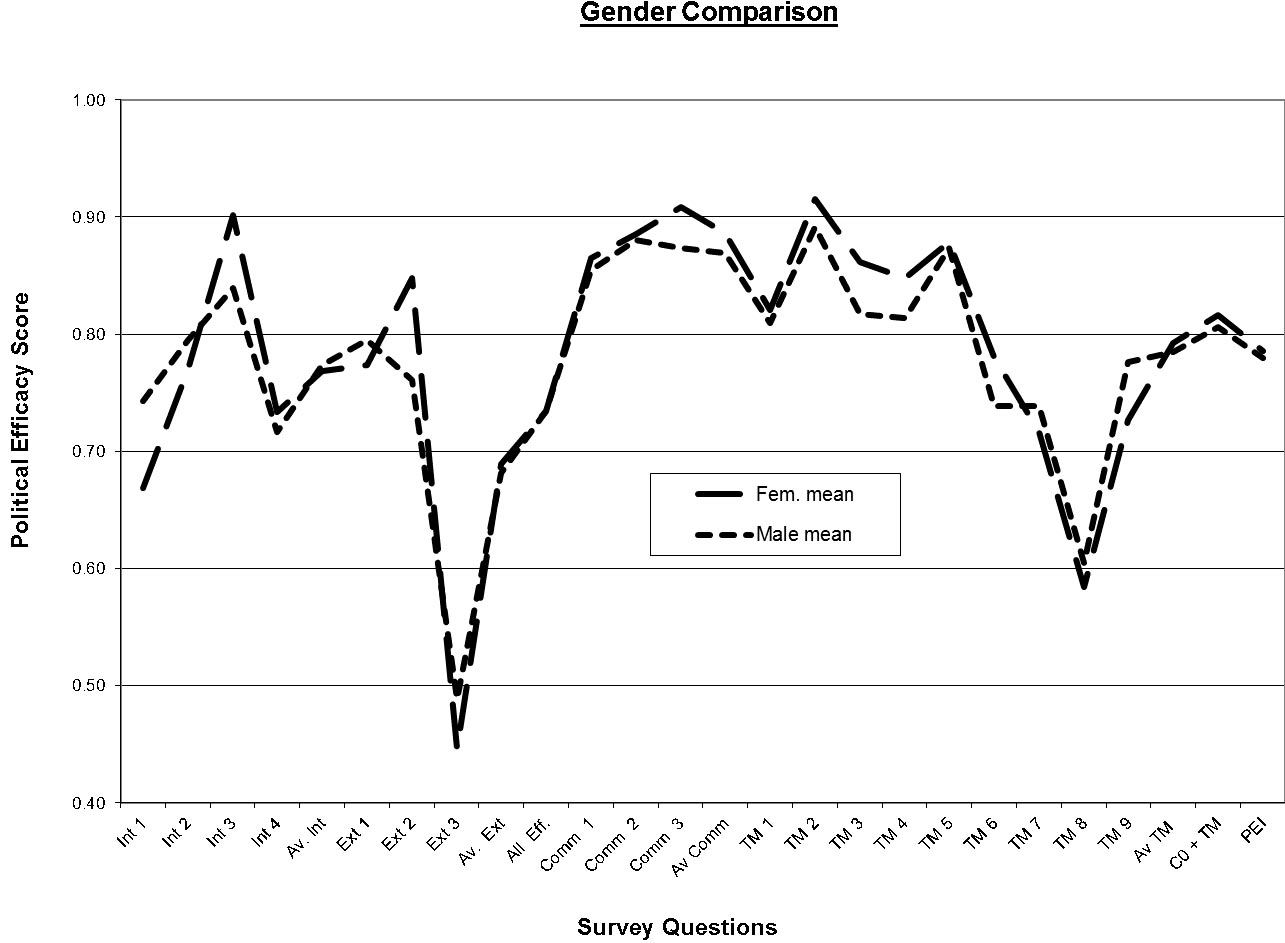

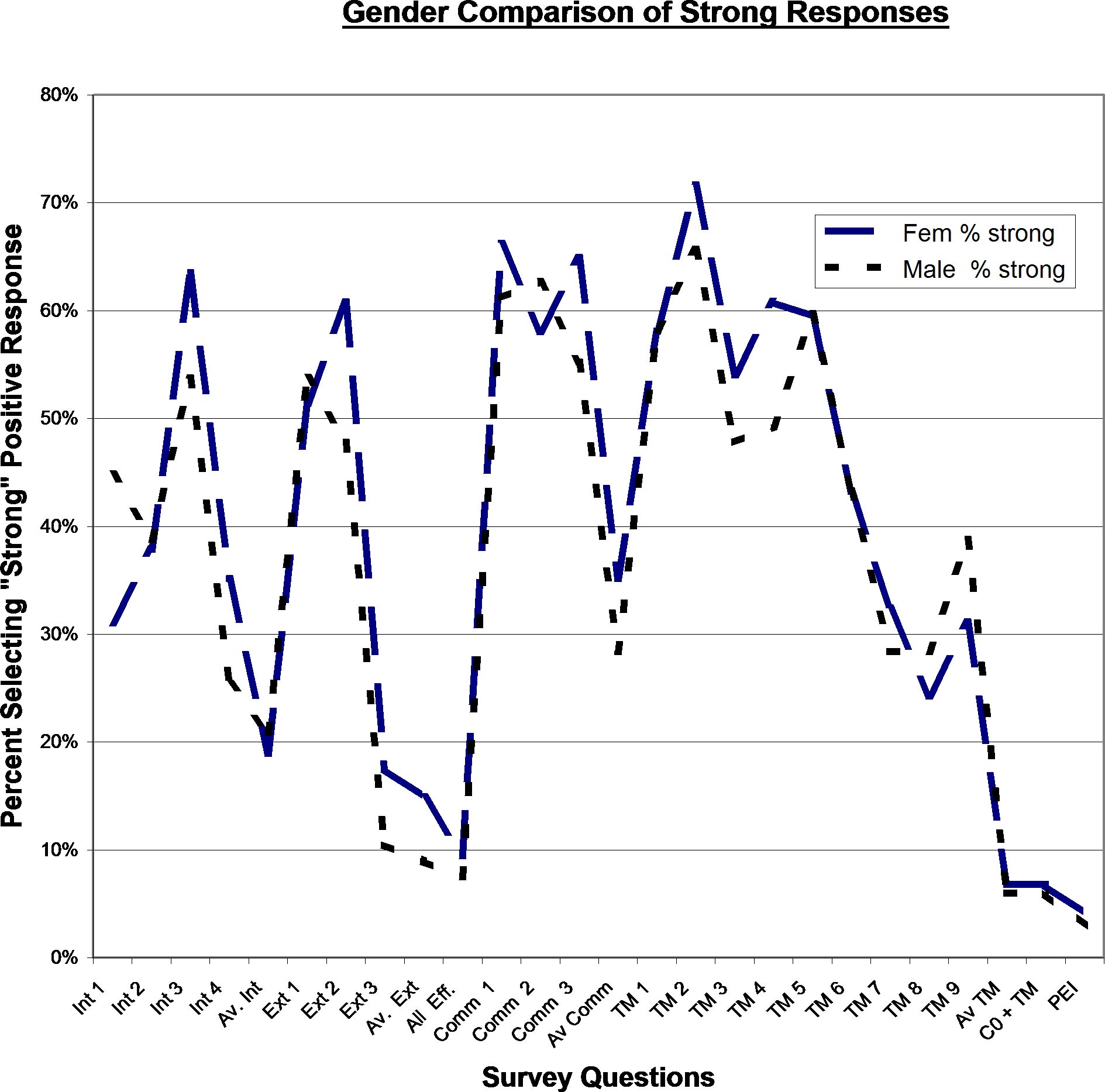

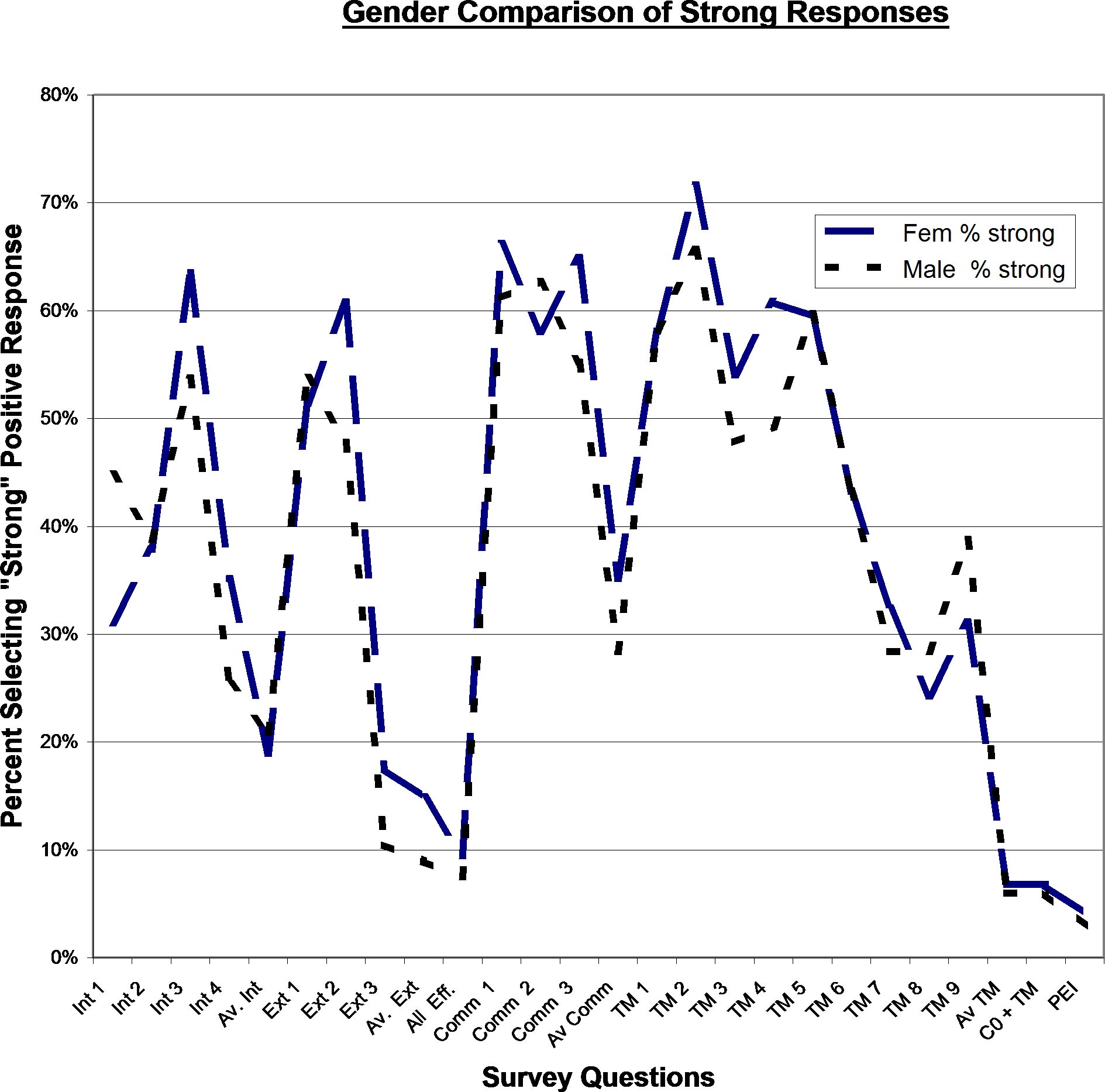

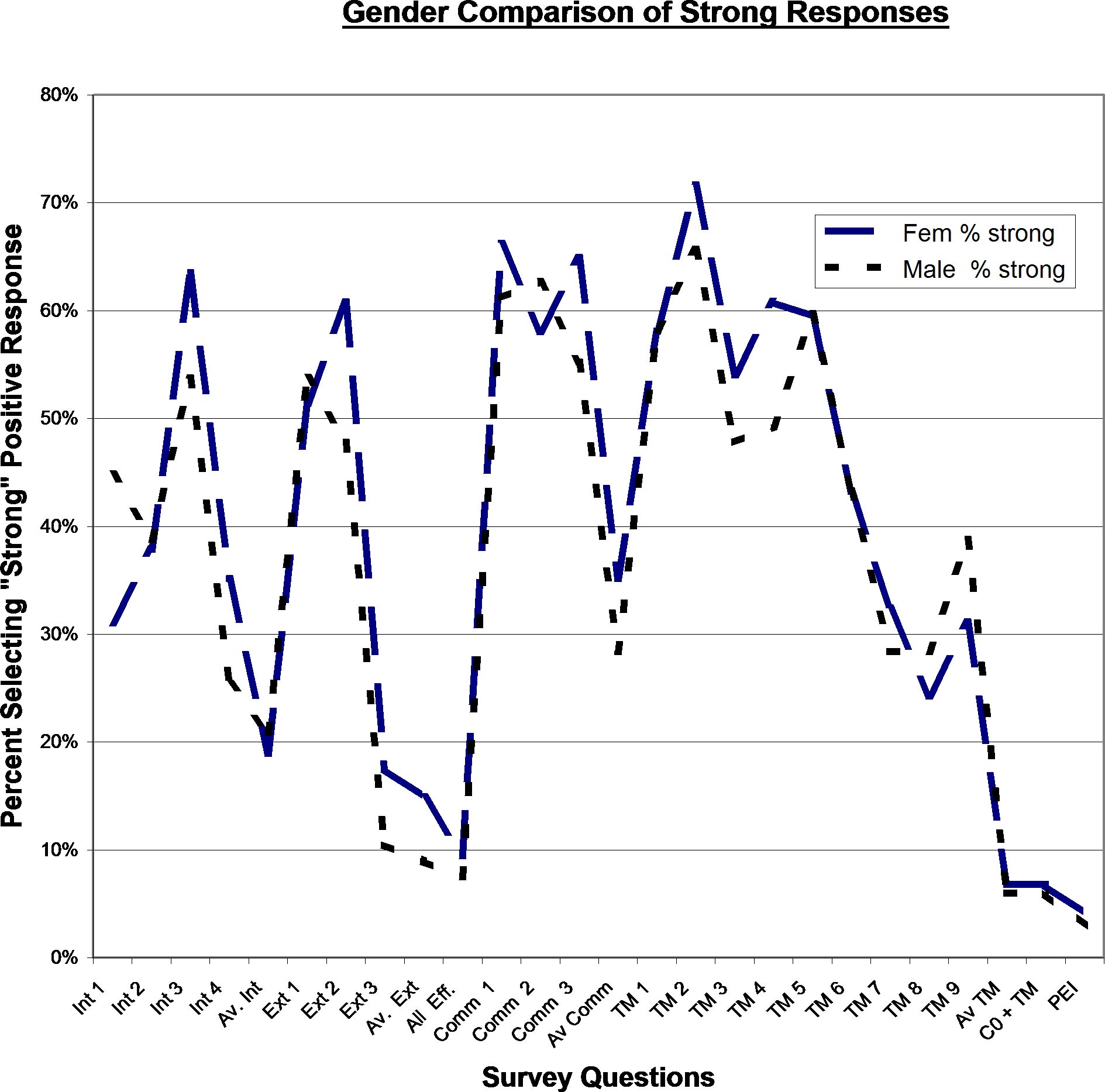

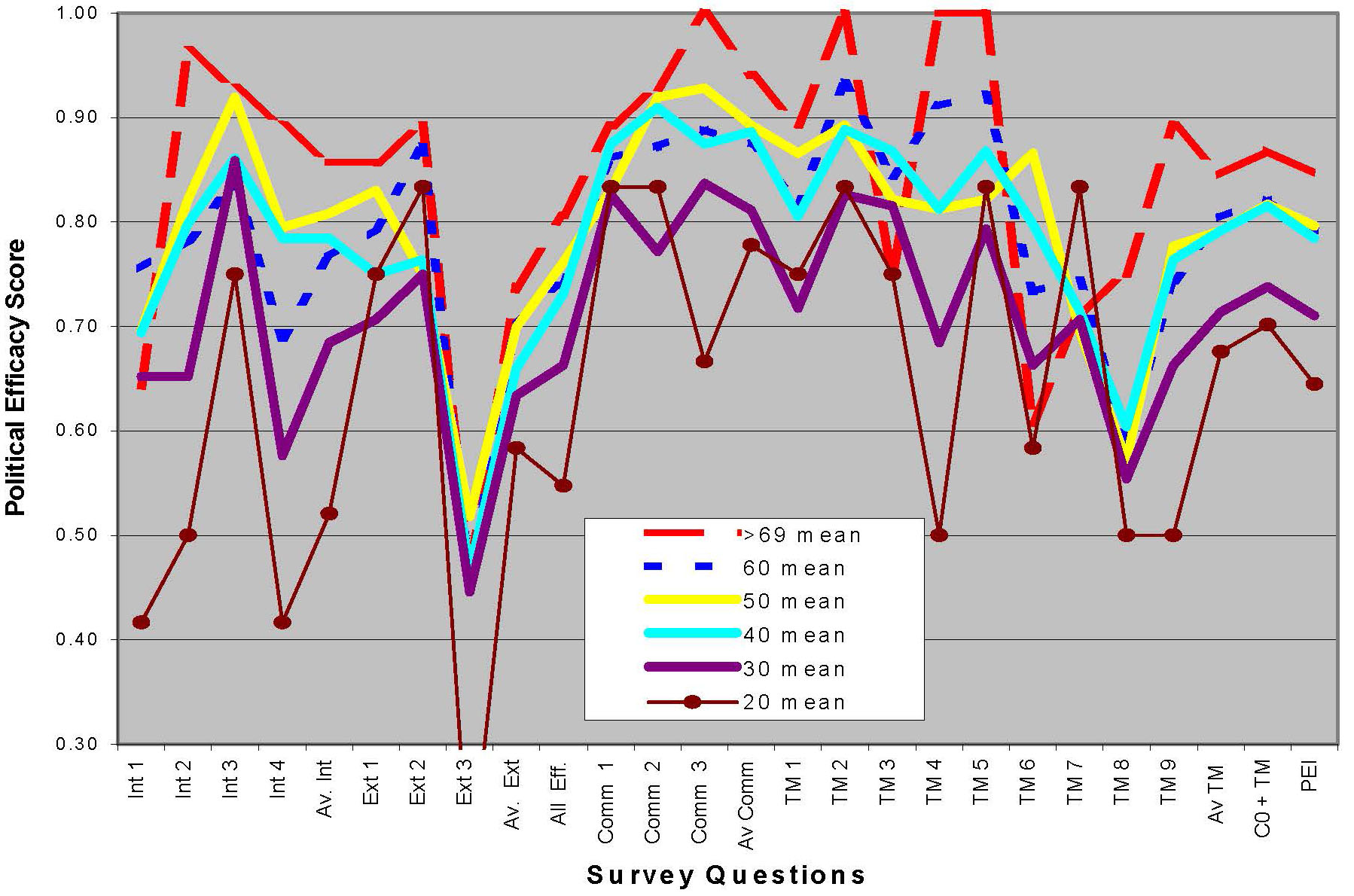

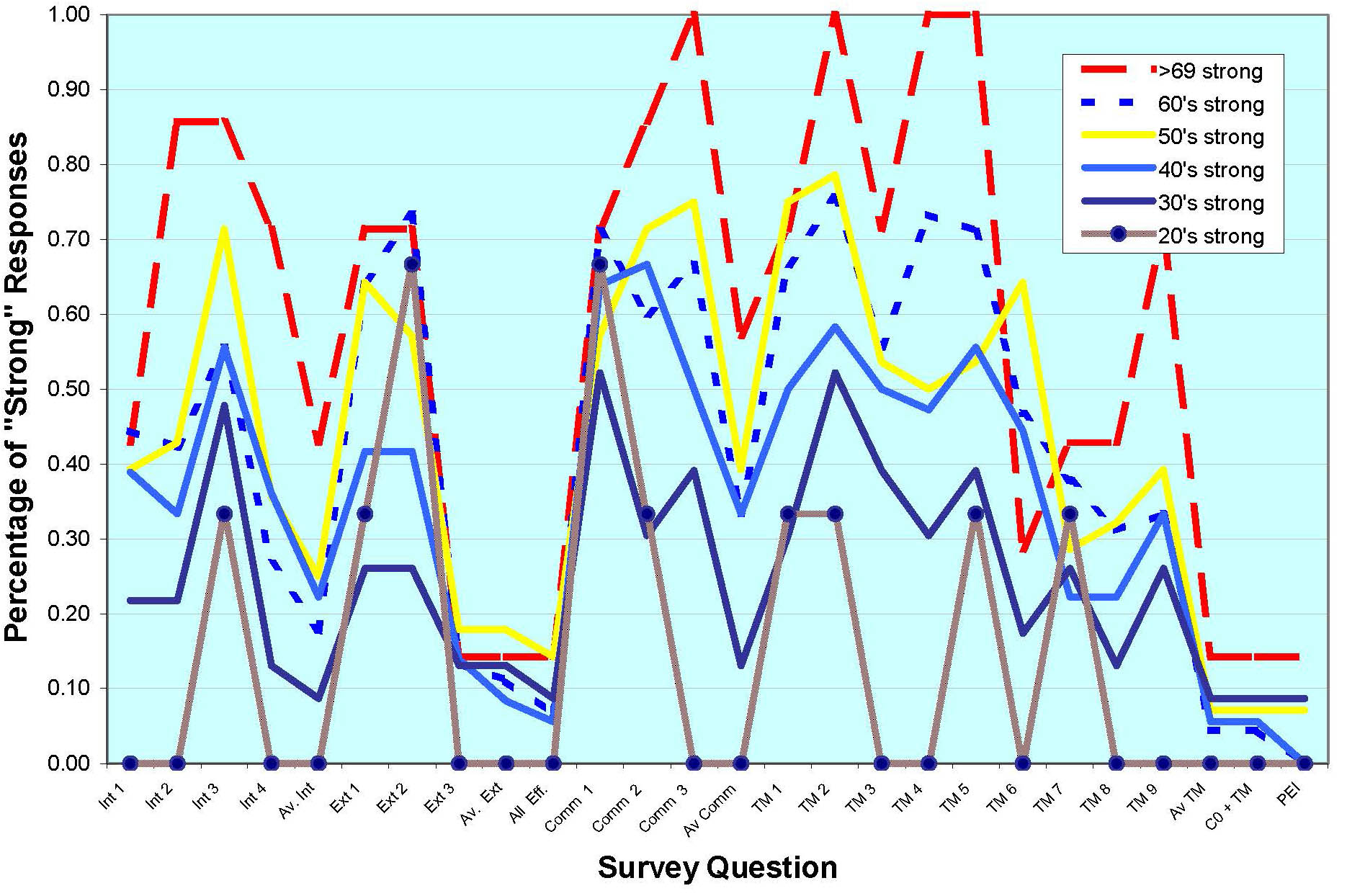

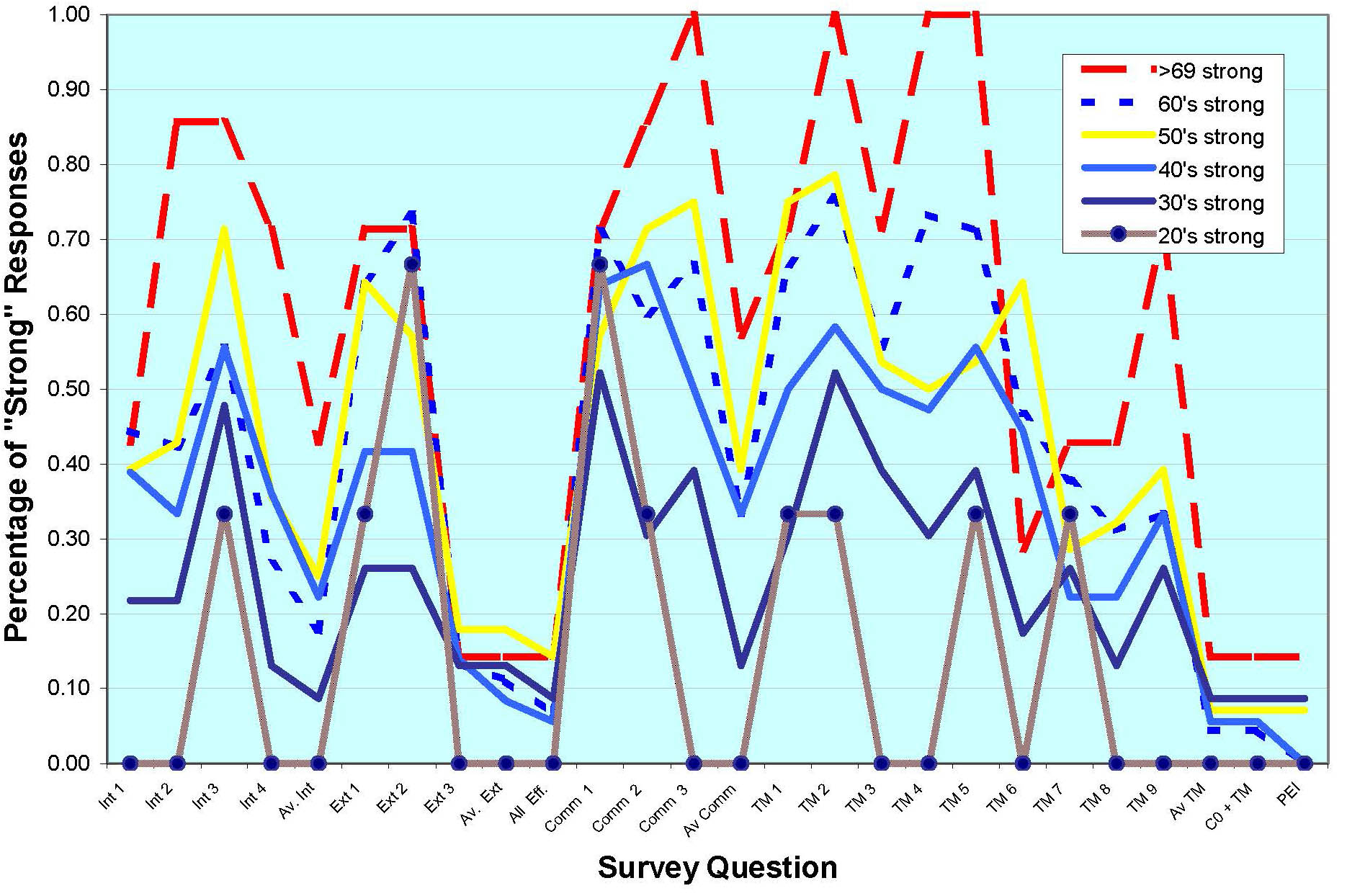

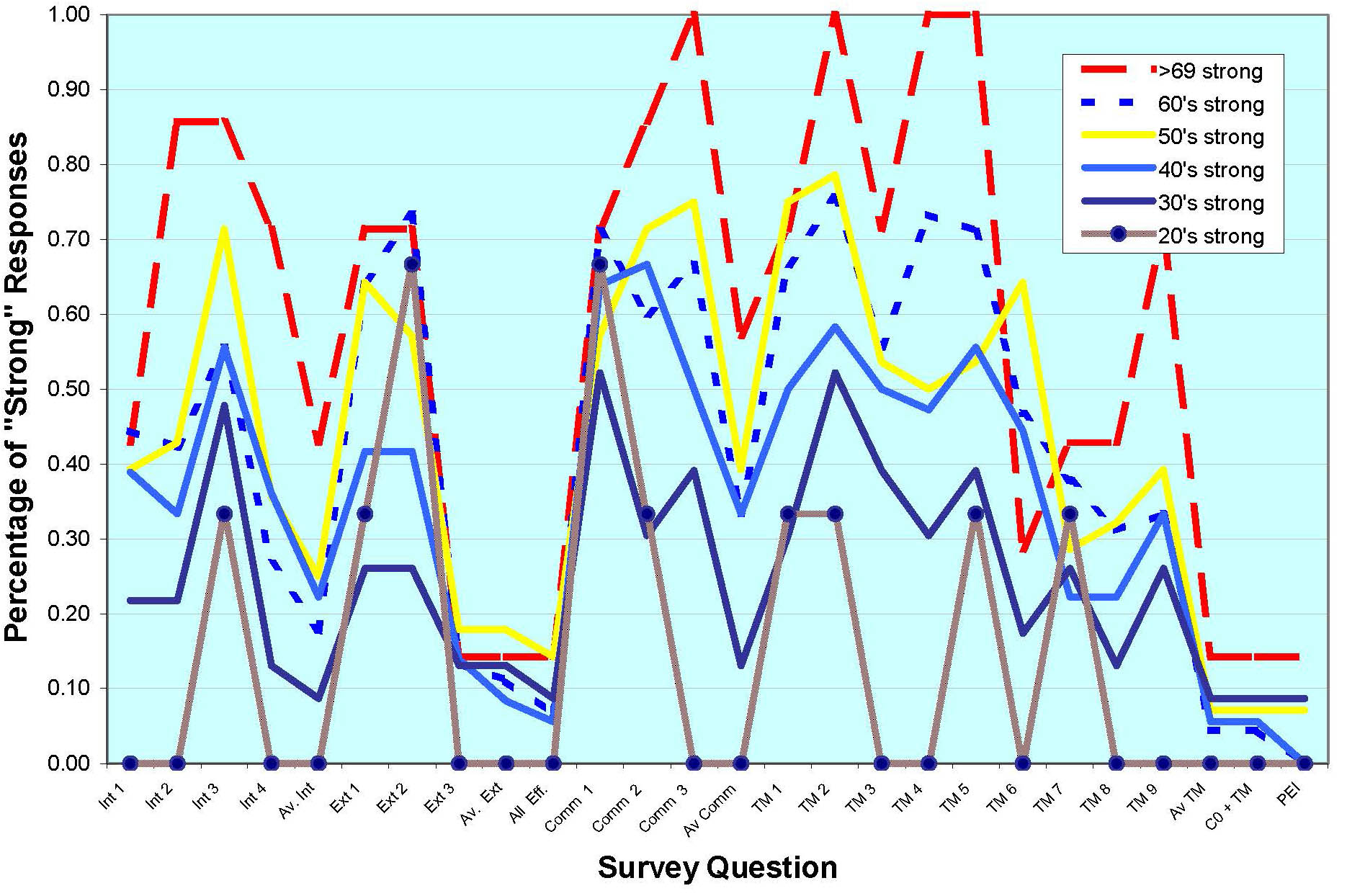

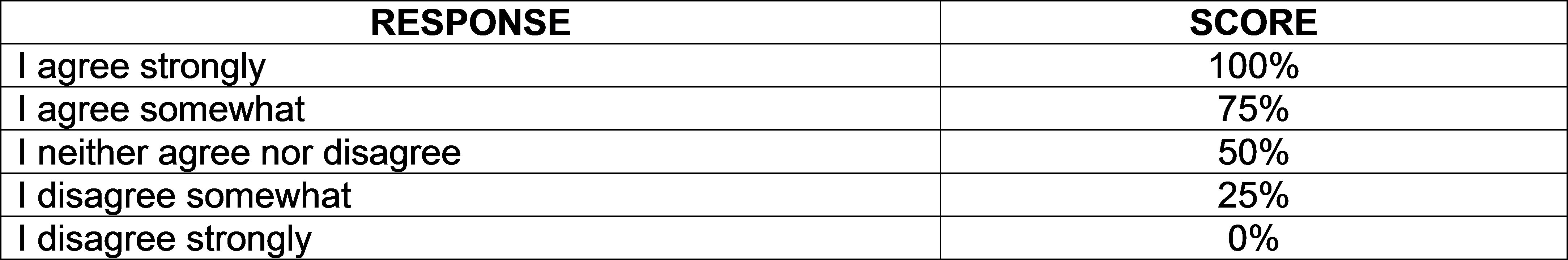

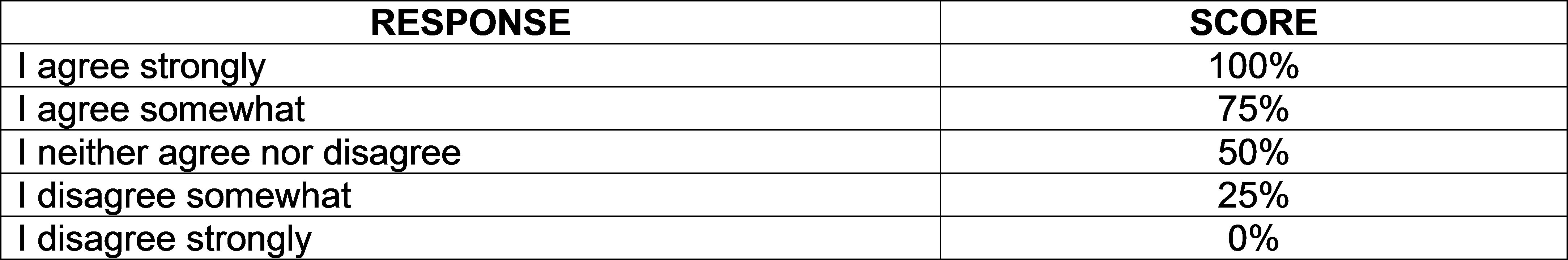

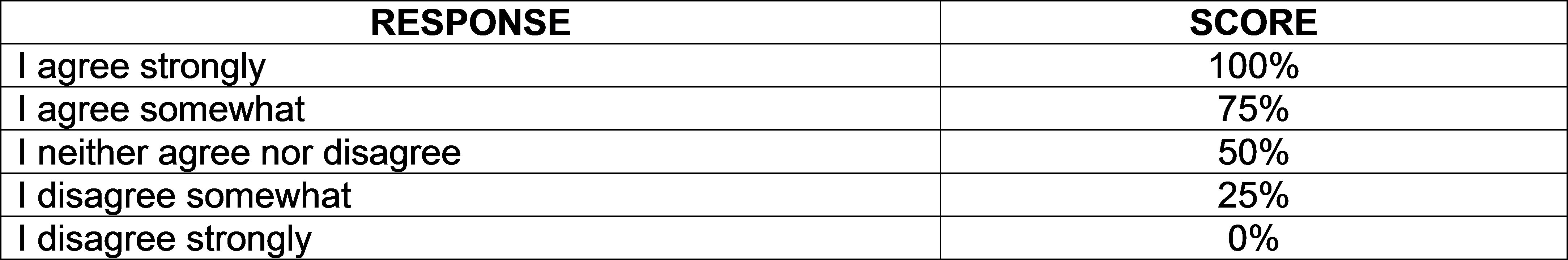

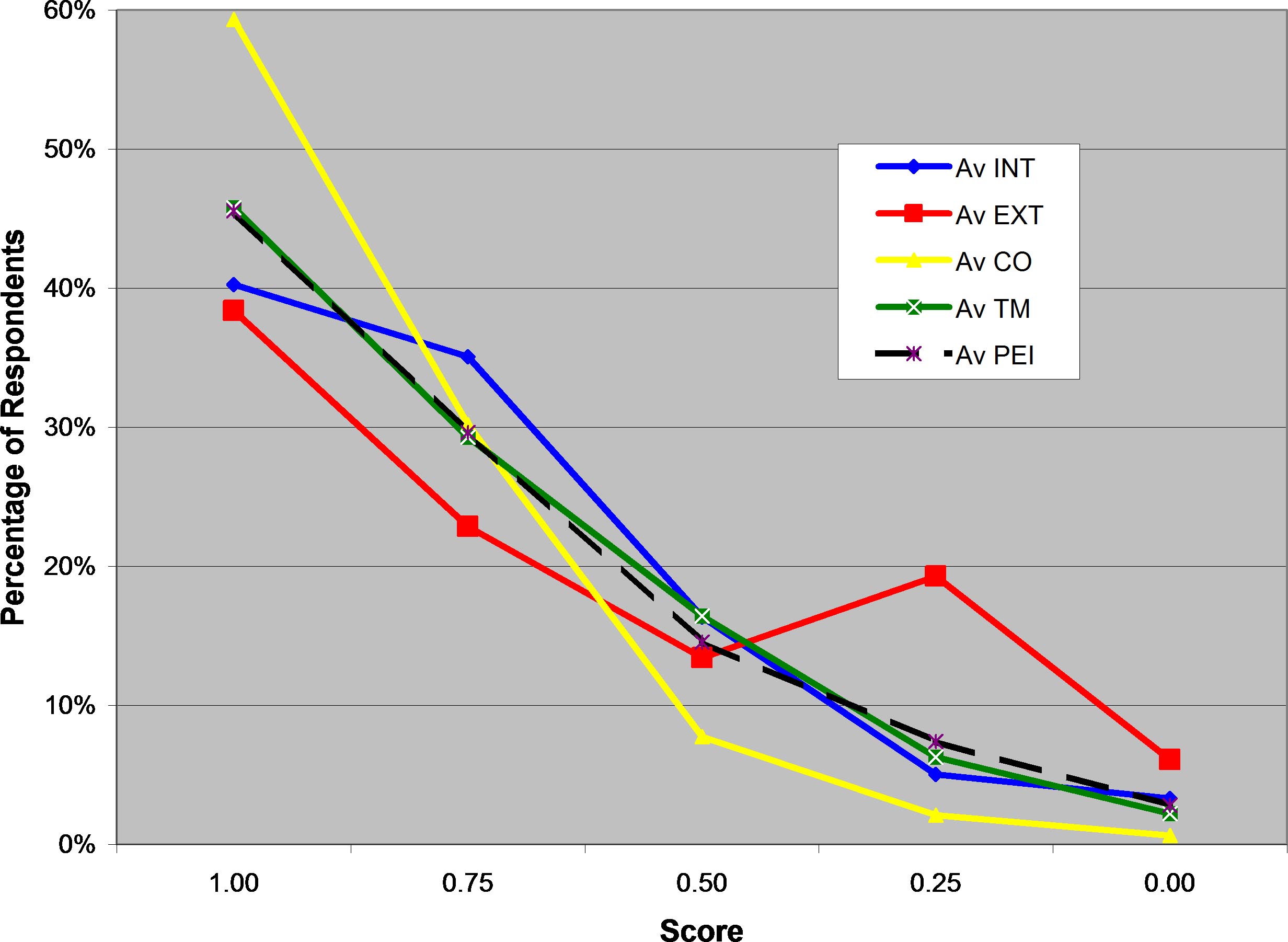

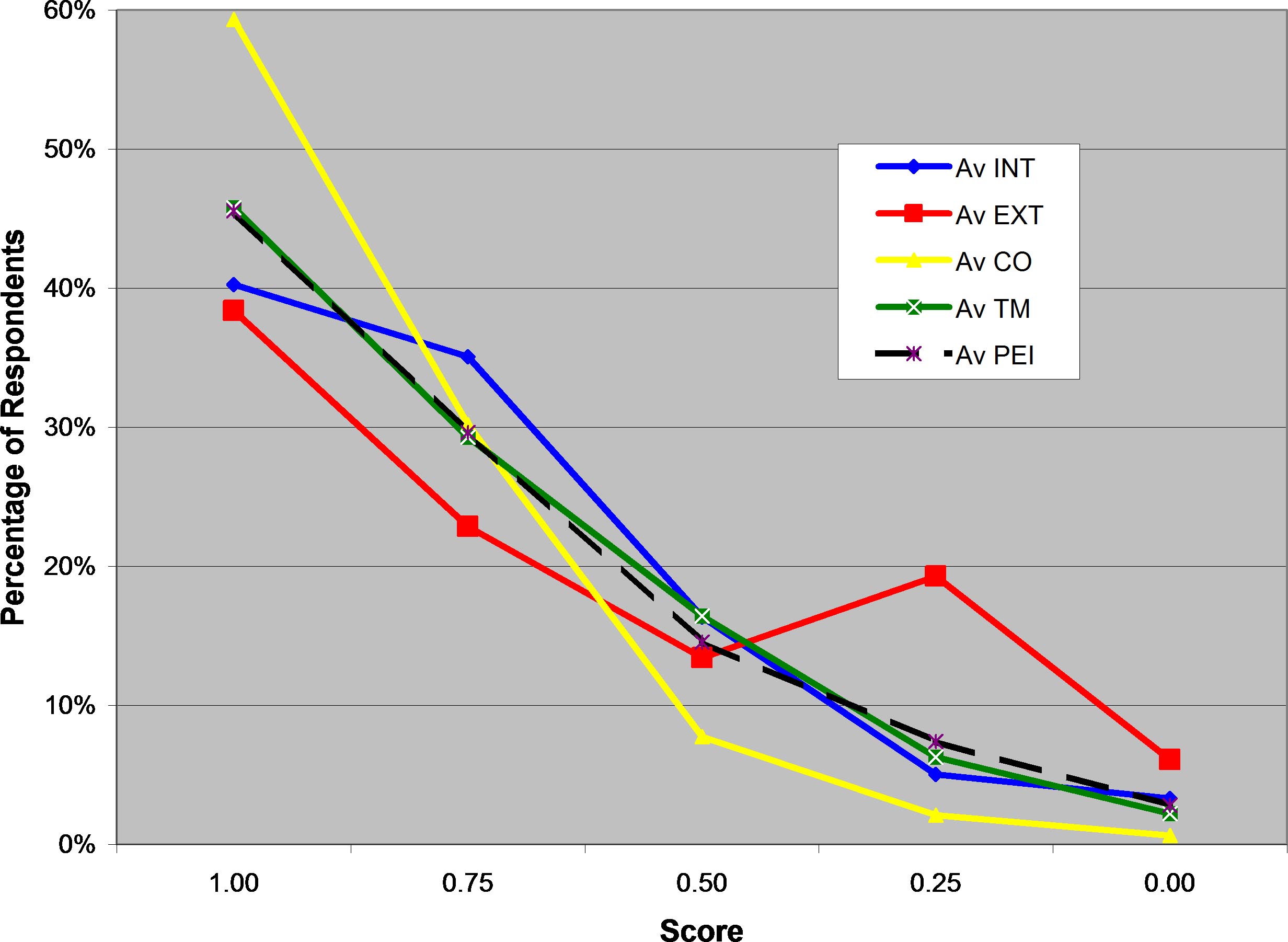

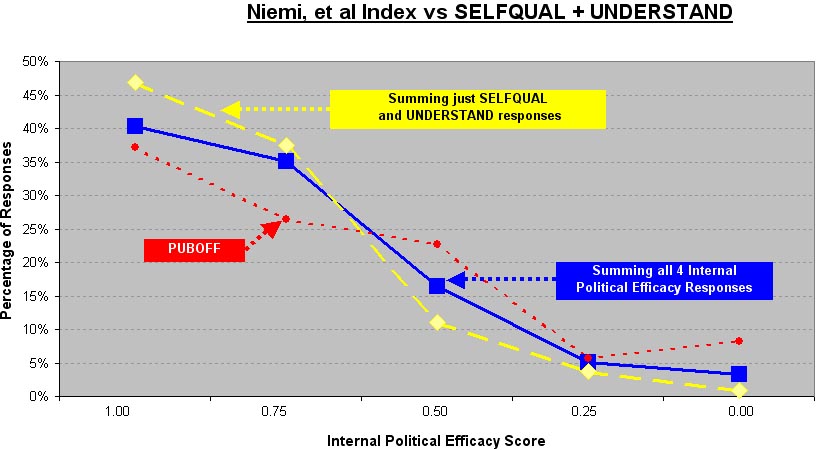

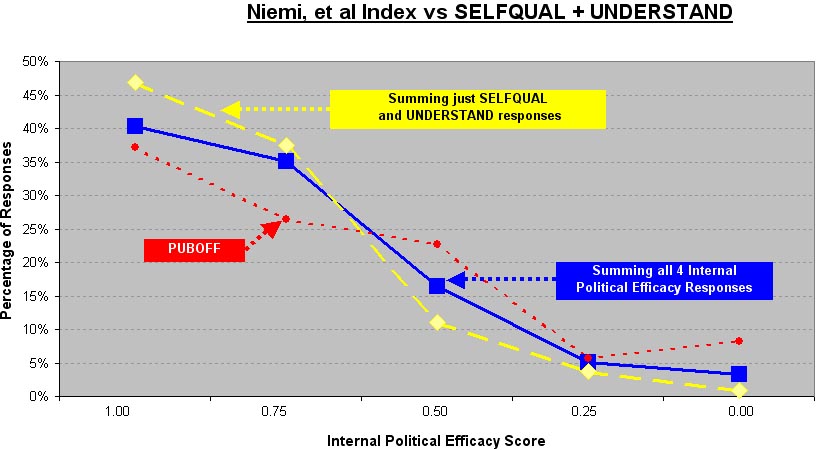

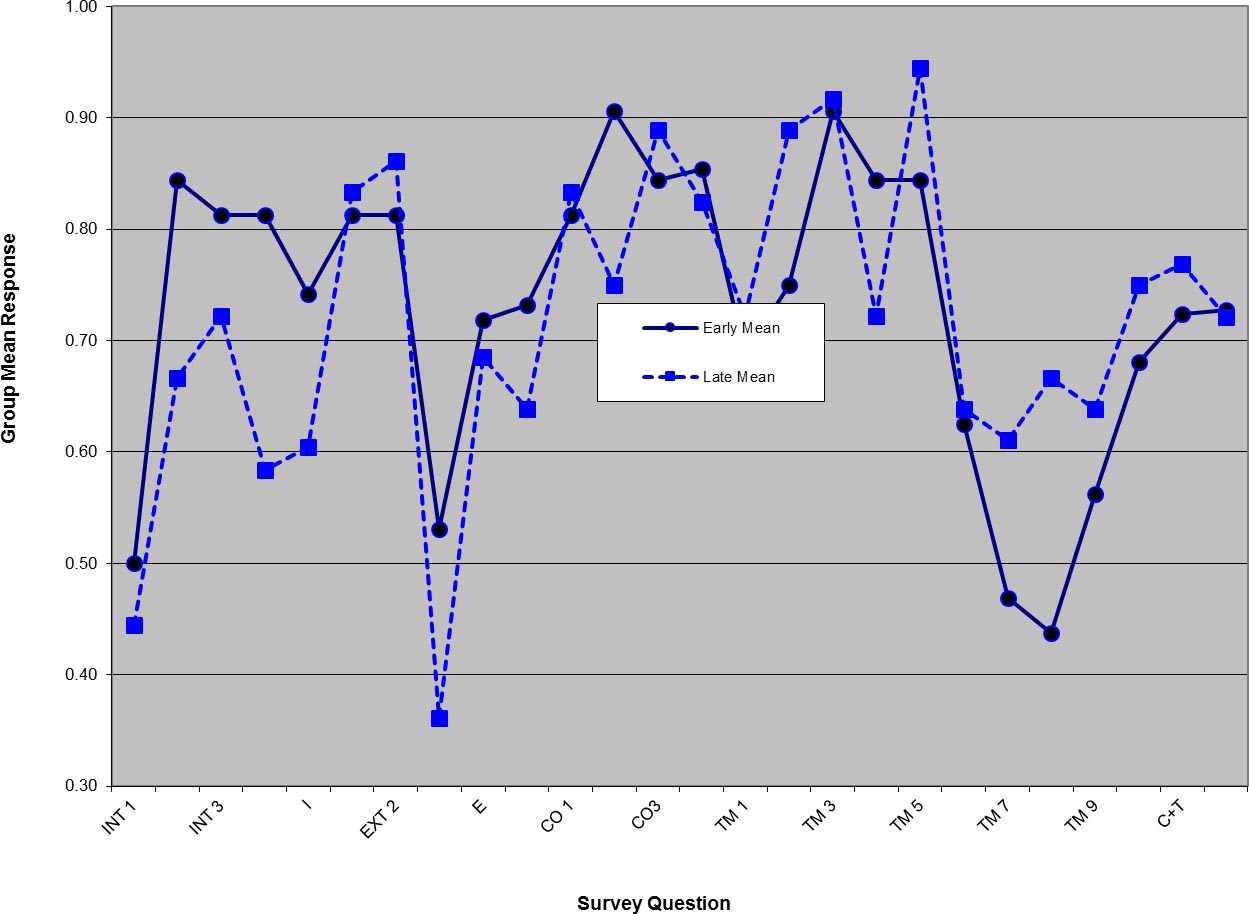

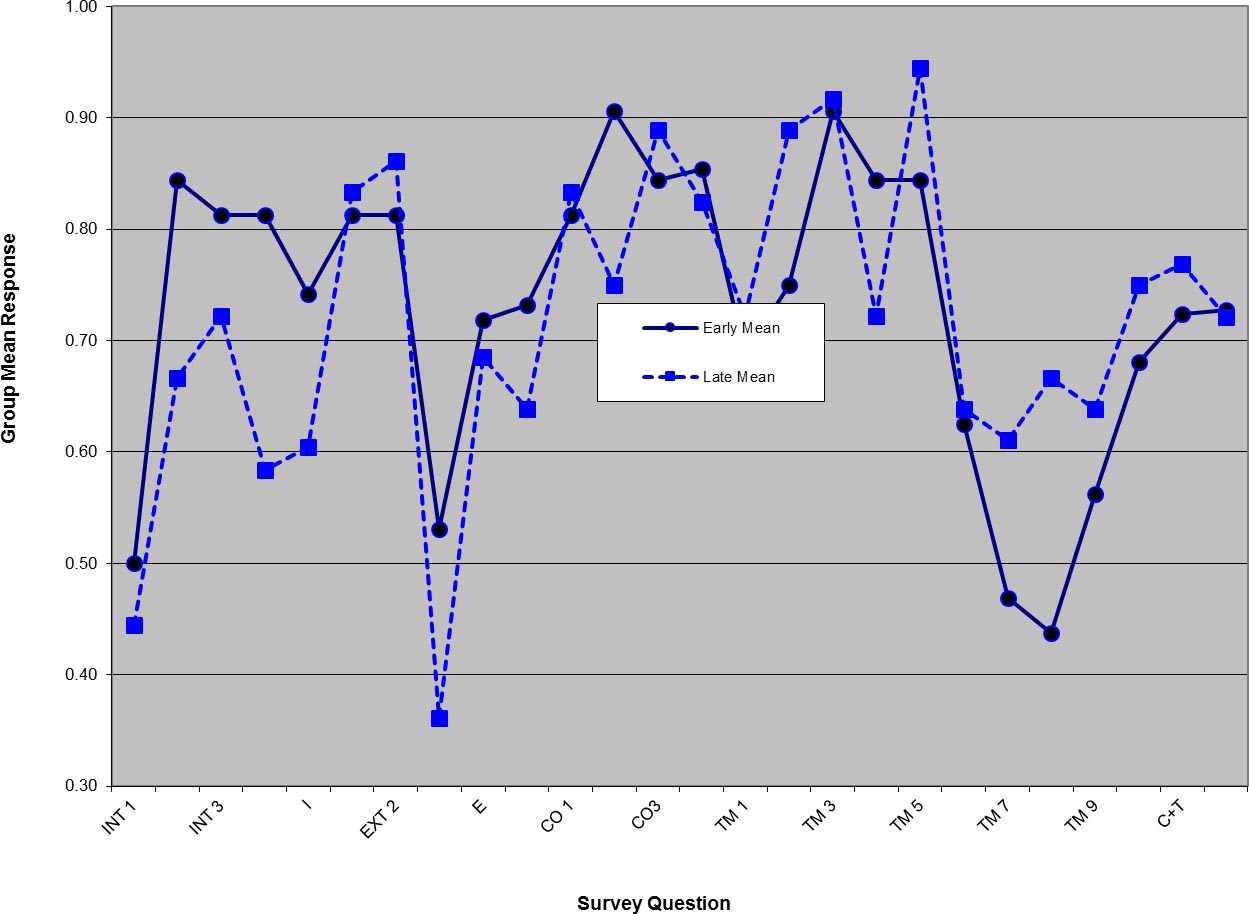

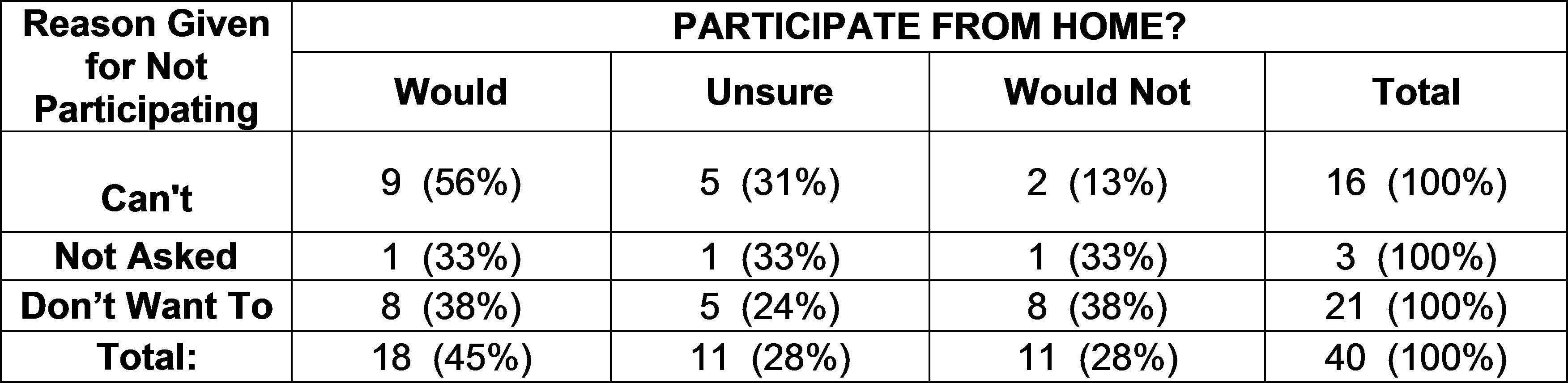

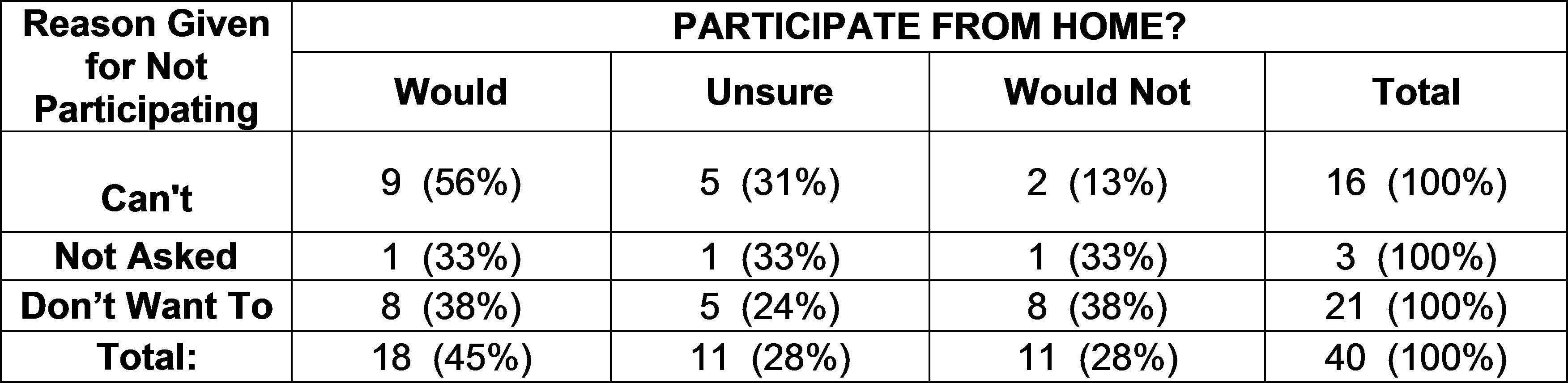

In this study the survey questions were answered by respondents checking one of 5 columns for each of the 19 questions[47]. In consonance with the NES political efficacy questionnaire, the columns were labeled (in order from left to right): “agree strongly”, “agree somewhat”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree somewhat”, and “disagree strongly”. The 5-choice answer approach represents a compromise between a 3-choice regimen (”agree”, “no opinion”, “disagree”) whose interpretation is unambiguous and a graded choice (select a number between 1 an 10, with 10 representing “strong agreement” and 1 representing “strong disagreement” with an optional “no opinion”) in which the respondent can shade the level of agreement. The former lumps all shades of agreement (or disagreement) into a single category. The latter provides shading but poses the problem of consistency- if 2 respondents select an answer of “8”, do they really have the same level of agreement or are their shading scales different? The 5-choice answer approach compromises in a way that retains both the benefits and difficulties of the 3-choice and the10-choice approaches. All respondents may not have the same threshold between “disagree somewhat” and “disagree strongly”. The hope is that with a sufficient number of respondents the “noise” associated with this variability will tend to be cancelled out. A further potential source of “noise” is that the choice of “I neither agree nor disagree” can be selected in the case where the respondent has no opinion or in the case where the respondent does not understand the question. Some respondents handled this latter case by leaving that questionnaire row blank.